Signed into law nearly 60 years ago, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in the U.S. based on “race, color, sex, religion, or national origin.”

Yet, as a historian who studies social movements and political change, I think the law’s most important lesson for today’s movements is not its content but rather how it was achieved.

As firsthand accounts from the era make clear, the movement won because it directly hurt the interests of white business owners. The 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, the 1963 boycott of Birmingham businesses and many lesser-known local boycotts inflicted major costs on local business owners and forced them to support integration.

The conventional narrative

A view common among scholars, activists and the general public holds that the Civil Rights Movement succeeded because violent attacks against peaceful Black protesters mobilized white public opinion in the movement’s favor.

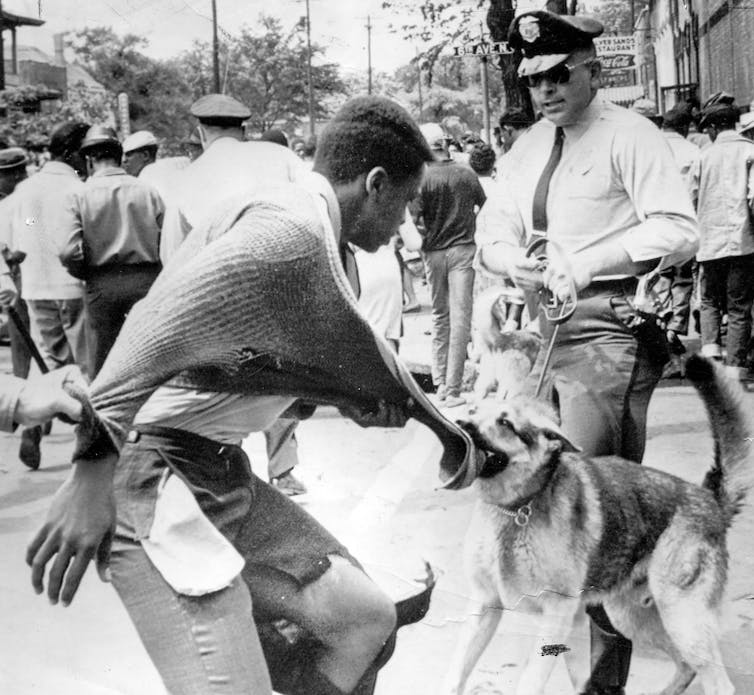

One of the most famous incidents occurred in Birmingham, Alabama, in May 1963, when the city’s public safety commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor, turned fire hoses and dogs on Black demonstrators.

The conventional wisdom is that Connor’s actions outraged Northern whites, and in response, the Kennedy administration sent federal troops to Birmingham and a civil rights bill to Congress.

But this view misunderstands the source of the movement’s power.

For one thing, it overstates public sympathy for the Civil Rights Movement. Three months after the attacks against Black protesters in Birmingham, for instance, almost two-thirds of the public opposed the famous March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom of August 1963.

Moreover, the Kennedy administration predicted that civil rights legislation would hurt the Democrats electorally. “The President never had any illusions about the political advantages of equal rights,” wrote Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger in his memoir “A Thousand Days.” “But he saw no alternative” given the movement’s actions.

So what were those actions?

Black organizers aimed to inflict maximal disruption on the white power structure, particularly economic elites. As Martin Luther King Jr. later recounted, “The political power structure listens to the economic power structure.”

By disrupting white businesses, often in a highly organized way, Black activists won social change.

A ‘devastatingly effective’ weapon

Economic boycotts in Southern cities such as Birmingham and Nashville, Tennessee, played crucial roles during the civil rights era.

A 20-month boycott by Black shoppers of downtown businesses in Greenwood, Mississippi, brought legal changes to the city’s hiring practices in 1964.

The most famous boycott occurred in 1955–56 in Montgomery, Alabama, where the nearly 13-month protest against segregated public transportation caused the city’s bus service to lose an estimated US$3,000 a day in fares.

Black people made up about 75% of public transportation riders. Instead of using city buses, they walked, formed car pools and used Black-owned taxi services. The boycott ended on Dec. 20, 1956, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that segregation on buses was unconstitutional.

By 1960, civil rights organizers were widely embracing this “economic weapon to fight segregation,” reported the national magazine Business Week.

Three years later, Time magazine wrote that boycotts had proved “devastatingly effective” in pushing white business owners and government officials to desegregate.

In Birmingham, for example, real estate tycoon Sidney Smyer led the elite push for integration. Smyer was a staunch racist, but he capitulated amid the boycott and related disruption.

“I’m still a segregationist,” he said in May 1963, but “I’m not a damn fool.”

During five weeks of boycotts, sit-ins and marches, Birmingham businesses had lost millions in sales.

Smyer and his fellow executives decided to cut their losses by integrating. They then dragged along the politicians, judges, school administrators and law enforcement officials.

That had been civil rights strategists’ plan from the start.

According to civil rights organizer Abraham Woods, they hoped that business owners hurt by the boycott in Birmingham would “pressure the city” to integrate.

Andrew Young, an adviser to King, later said that “Bull Connor made the impact greater, but the dynamics would have taken effect without Bull Connor and the dogs. … When the demonstrations were so massive and the economic withdrawal program was so tight, literally, the town was paralyzed.”

Changing the law after Birmingham

The Birmingham victory inspired other Black people to rise up. Kennedy’s Department of Justice reported another 2,062 Black protests in 40 states by the end of 1963.

It also led Kennedy – 28 months into his presidency – to propose a civil rights bill, in June 1963.

Even as he tried to dissuade Black leaders from marching on Washington, Kennedy admitted that the disruptive boycotts and protests “had made the executive branch act faster and were now forcing Congress to entertain legislation,” as Schlesinger reported in his book “A Thousand Days.”

Kennedy also feared the radicalization of Black consciousness after Birmingham. If the federal government didn’t deliver moderate reform, the “colored masses” might embrace “the mindless radicalism of the Negro militants,” as Schlesinger described the president’s logic.

Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 meant the civil rights bill fell to his successor, Lyndon Johnson. After a heated battle in Congress, Johnson signed the bill into law on July 2, 1964.

By causing massive and sustained disruption to ruling-class interests, particularly businesses, Black organizers who were formally excluded from political power were able to force legal change.

The lesson is that major legislative reform requires mass disruption outside the electoral and legislative spheres. Without that disruption, it will be very difficult to win any law that negatively affects entrenched power-holders.

Kevin A. Young does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.