Between now and Election Day, journalists are going to spend a lot of time talking about Michigan as one of a group of “crucial battleground states” in the 2024 campaign. There will be stories about the state’s blue-collar roots and the importance of the vote from working-class white people, African Americans, Arab Americans, college students and rural communities.

All of those stories will be true, to some extent, because in the past few elections Michigan has become a state where the little things – low turnout with this voter group, extra enthusiasm with that one – matter a lot.

It wasn’t always this way. Until fairly recently, Michigan was a relatively safe bet, at least in presidential politics. From 1992 to 2012, during six presidential elections, Michigan voted Democratic regardless of what the nation did as a whole. In 2000 and 2004, Republican George W. Bush won the presidency, while Michigan voted for Democrats Al Gore in 2000 and John Kerry in 2004.

Then Donald Trump changed the state’s electoral equation.

Many puzzle pieces

Republican presidential candidate Trump won the state of Michigan in 2016 by activating specific segments of the electorate. He won with a combination of enthusiasm among some voter groups for him and disdain among others for Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton. The evidence of those voter attitudes is all over the results data from 2016.

You can see the enthusiasm for Trump in the results from Macomb and Monroe counties. These are two blue-collar suburban counties around Detroit that we call “middle suburbs” in the American Communities Project, a journalism effort I direct at Michigan State University. These counties are home to many of the autoworkers in the big plants and smaller auto shops around Detroit. Both those counties flipped to Trump in 2016 from Barack Obama in 2012, and both produced more total votes – a sign of Trump’s little-noted, blue-collar suburban surge in 2016.

The disdain for Clinton is apparent in Wayne and Genesee counties, the respective homes of Detroit and Flint, two cities with large African American populations. Clinton still won both Democratic strongholds, but her margins of victory were smaller than Obama’s in 2012, and fewer people voted in each county.

In 2012, Wayne County produced about 818,000 votes, and Obama won it by about 47 percentage points. That was largely in line with recent winning margins by Democratic candidates. The Democratic presidential candidate won the county by 40 points or more in every contest from 2000 to 2012.

In 2016, Wayne County produced only 783,000 votes, and Clinton won it by 37 percentage points. Genesee County followed a similar track. In 2016, it produced 6,000 fewer votes than 2012, and Clinton won it by a relatively meager 9 percentage points, after Obama had won it by 28 percentage points four years earlier.

In 2020, Joe Biden recaptured Michigan, and won the White House, by engaging and reengaging voter groups, particularly African American voters, that didn’t come out in 2016. Turnout in Wayne County spiked to 874,000 votes.

Biden also got bigger turnout and bigger margins out of Washtenaw and Ingham counties, the respective homes of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University, known as “college towns” in the project I run. Trump also saw his margin shrink in blue-collar Macomb County.

The push and pull among these groups will dictate what happens in Michigan this fall. There are a series of key questions and voter groups to watch.

Can Trump or Biden do it again?

Can Biden get big turnout and support among the large African American populations in places such as Flint and Detroit? The early signs suggest there could be concerns here. Polls consistently show low enthusiasm among Black voters.

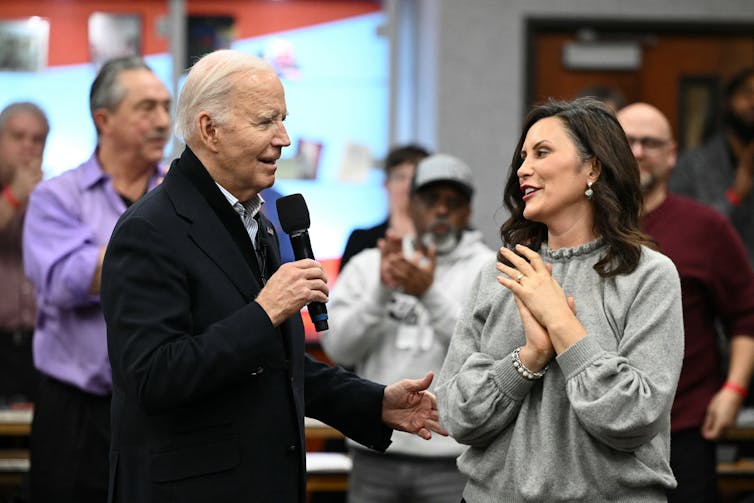

What about Trump’s support among those blue-collar suburbanites in places such as Macomb and Monroe counties? Those places will almost certainly vote for Trump again this fall, but margins will be key. Since 2016, the political leaning among those voters looks more complicated. There were unenthused Democrats in these communities too in that 2016 race, and since that election they’ve been more likely to come out to vote. For instance, Michigan’s Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer won Macomb in her 2018 campaign and her 2022 reelection. Can Trump recreate his huge 2016 win with those voters in 2024?

Young college-age adults are usually some of the hardest voters to turn out for an election, but, again, they are a key Democratic constituency. Voters in “college town” counties such as Washtenaw and Ingham didn’t show up in big numbers in 2016, but they did in 2020, largely because of their dislike of incumbent Trump. They also came out in droves in 2022 to reelect Whitmer, but that may have been because of a ballot proposal that enshrined abortion rights in the state.

This year, polls show young voters are unenthused about Biden, and there will be no abortion measure on the ballot in Michigan. How does that effect their turnout? Do they even consider voting for Trump or a third-party option because they oppose some Biden policies?

Small shifts can mean a lot

One of the policies that may turn younger voters off is the U.S. government’s position on the Israel-Hamas war in the Middle East, which affects another important voter group in Michigan – Arab American voters.

There has been a lot of attention on this group in the 2024 political coverage of Michigan because of the large concentration of Arab American voters in the state. It’s not a massive population, about 225,000 people in a state of more than 10 million, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But the state has been close lately, with Trump winning it by about 11,000 votes in 2016 and Biden capturing it by about 150,000 in 2020. Again, in Michigan, small shifts can mean a lot.

Those aren’t all the factors that could influence the election’s outcome, of course. There are a lot of rural counties in the northern parts of Michigan that tend to favor Trump. Even though they don’t produce a lot of votes individually, together they can add up. A surge in turnout there could matter.

There are also the high-income, highly educated suburbanites around Detroit and Grand Rapids who are increasingly voting Democratic.

In short, there are no simple answers. That’s why the election will likely be close. But keep an eye on these voter segments and regions and you’ll get a sense of where things are headed in the complicated jigsaw puzzle that is Michigan this fall.

Dante Chinni receives funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation for his work on the American Communities Project and is a contributor to the Wall Street Journal.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.