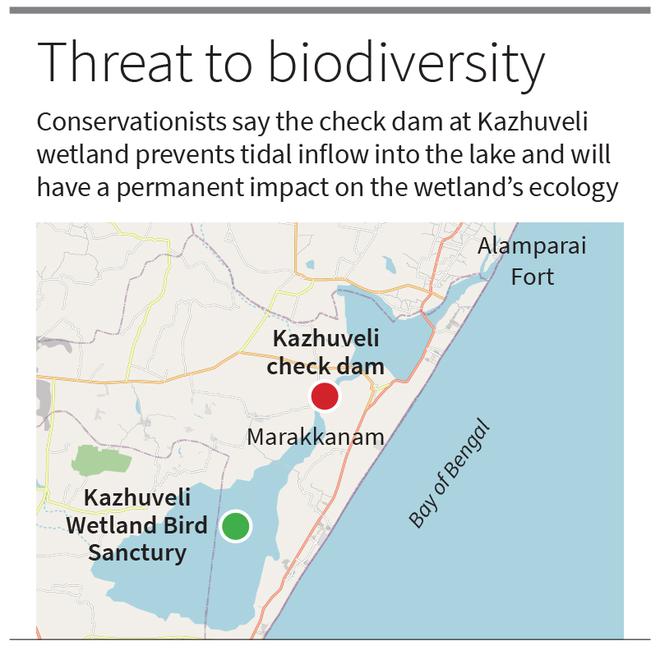

In 2021, the Public Works Department (PWD) built a check dam on the Kazhuveli wetland, located in Vanur and Marakkanam taluks of Villupuram district, hoping to convert it into a freshwater lake. While it sounds like a good plan, it could spell disaster for the bird sanctuary and its associated biodiversity.

Very few people know about the PWD’s ₹161-crore project. Activists say much of the outside world has no clue about the work, as the check dam is located 10 km downstream. As part of the plan to reclaim the tank for storing freshwater, the check dam was built to prevent seawater intrusion, while a bund along the length of the wetland would contain the freshwater.

Through this project, the PWD aims to recharge groundwater for villages around the wetland and store drinking water for Villupuram. There is even a plan to supply water to Chennai, as is being done from the Veeranam tank. However, conservationists point out that blocking seawater inlet into Kazhuveli will change its characteristics and affect bio-stability of the area, declared a bird sanctuary in December, 2021.

The diverse ecosystem

Kazhuveli, or Kaliveli, meaning ‘Passage to Backwaters’, is a brackish water wetland, which feeds into the Bay of Bengal through the narrow 8-km-long Uppukalli creek and the Yedayanthittu estuary. Over 160 irrigation ponds drain into the sea through Kazhuveli, which is about 10.5 km in width, 28.5 km in length, and spread over 73.01 sq. km. Listed as one of Tamil Nadu’s 141 prioritised wetlands, Kazhuveli is also a wetland of international significance and a potential Ramsar site, says the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change’s ‘Wetlands of India’ portal.

The wetland is home to over 200 species of birds and is recognised as an important stopover and breeding ground for about 40,000 migratory birds. With the annual migratory season about to start in a few weeks, thousands of waterbirds and shorebirds, including several long-distance migratory birds in the Central Asian Flyway, will use it as a wintering ground. The birds found in the Kazhuveli bird sanctuary include spot-billed pelicans, darters, cormorants, herons, egrets, storks, black ibis, spoonbill, flamingo, spot-billed duck, garganey, common pochard, sandpiper, coots, shanks, and terns. Many of them have been categorised as ‘vulnerable’ or ‘near threatened’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). According to a 2016 report, ‘Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas in India-Tamil Nadu’, by the Bombay Natural History Society and Indian Bird Conservation Network, the area regularly holds over 30,000 ducks in winter, 20,000-40,000 shorebirds, and 20,000-50,000 terns during the migration period. As the lake fills up with freshwater in November, numerous aquatic plants germinate, it says.

Reclaiming the tank

The PWD obtained Coastal Regulation Zone clearance in November 2020 for reconstructing a dilapidated check dam, with sub-surface dyke and shutters, across the Uppukalli creek, between the Kazhuveli lake and the Yedayanthittu estuary. The objective is to reduce the quantum of freshwater draining into the sea and arrest the seawater intrusion into the Kazhuveli lake. “The Marakkanam block receives one of the highest amounts of rainfall. Almost 40 tmc ft [thousand million cubic feet] of water drains into the sea through Kazhuveli without being used,” said a PWD official. According to him, there was a dam at the same place built by the British in 1916 and it had functioned till the late 1970s when it was destroyed after years of neglect. “This is not a new project. The dam was already there. We are only rebuilding what was already there,” he insisted, pointing to the remains of the old structure right in front of the new check dam.

According to the Detailed Project Report (DPR) for reclamation of the Kazhuveli tank, during high tide, seawater enters the tank as the tail-end regulator (the dam) was in a dilapidated condition. So, groundwater has deteriorated in adjoining villages. Further, owing to high salinity, aquaculture and prawn culture farms and salt pans have come up, and they require heavy pumping of seawater into the land, adding to the problem. The primary reason for implementing the project is to improve drinking-water availability in dry areas of Villupuram district, says the DPR. It is also being said that the tank will be used to supply drinking water to Chennai. “This project will create storage of 3.3 tmc ft for one filling and 6.6 tmc ft for two fillings,” the DPR notes. This means that the Kazhuveli tank will have a slightly larger capacity than the Vaigai Dam, which holds 6.14 tmc ft, PWD officials say.

‘It’s a disaster in short’

Coastal wetlands are unique ecosystems that form a transitional zone between the ocean and terrestrial ecosystems. Through tidal action, which brings about fluctuations in water levels and chemical and physical properties on a daily basis, the dynamics of these wetlands create varied habitats such as tidal marshes and estuaries, mangroves, seagrass meadows, inter-tidal flats, tidal salt marshes and tidal freshwater — all often falling within a short distance of each other. For instance, coastal wetlands not only support fish adapted to freshwater, brackish water and salt water, the nutrient-rich sediment deposit brought by rivers help sustain mangroves and seagrass beds, which, in turn, form a nursery for marine fish and shrimps.

The check dam, says conservation biologist Priya Davidar, is located at a critical site and prevents tidal inflow to the lake. “It’s a disaster in short,” she says, adding she is not sure if the check dam will recharge groundwater, as planned. “It will only result in the degradation of this biodiverse ecosystem and increase salt water intrusion.” A three-member committee, headed by Chief Wildlife Warden Srinivas R. Reddy, inspected the dam in 2022 and concluded that the project would permanently alter the ecology and characteristics of the brackish Kazhuveli lake. “This would change the brackish Kazhuveli lagoon into a freshwater lake, which will have a permanent impact on the ecology of the sanctuary,” the committee’s report said. The blocking of the brackish water inlet would affect mangroves and migratory birds, it added. The committee said the project had to be stopped or suitably modified to allow periodic tidal movements of brackish water into the sanctuary to sustain the ecosystem and maintain the characteristics of the Kazhuveli bird sanctuary as an estuarine lake system.

At a time when water requirement in towns and growing metropolises is only increasing, the PWD official says the Kazhuveli tank will be a blessing. “It’s an invisible treasure,” he says, adding that the only hiccup in the completion of the project is clearance for around 120 hectares of land from the Forest Department for bund construction. “If the bund is raised, prawn farms cannot let water into the lake and the freshwater in it will help over 20 villages,” he says. Additionally, the reclamation of the Kazhuveli tank includes building small islands amid the wetland for birds to congregate and find prey. “When all is said and done, drinking water is important,” the official underscores.

Manjanathan, a resident of Pudupakkam, says the groundwater in his village is not fit for drinking. He hopes the freshwater tank would change the situation. The village gets water from a borewell sunk one kilometre away. “If a bird from another country needs water, then what about us,” he asks. However, questions remain on whether a dam is the best way forward. Steps should be taken to restore water quality by stopping the sources of pollution and illegal dumping of wastewater, suggests Ms. Davidar. “Not sure that constructing this dam will improve water quality. Dams are slowly being dismantled in Europe and North America because of the damage they do to biodiversity. Therefore, putting up a dam across a natural lagoon is a retrogressive step.” According to her, restoring irrigation tanks in the huge watershed area at the head of the lake will do far more for restoring groundwater than a dam near the estuary.

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) on August 24 kept in abeyance the environmental clearance granted to two fishing harbours at Alamparaikuppam and Azhagankuppam in the Yedayanthittu estuary. It expressed surprise over missing detailed studies on turtle-nesting grounds, mangroves and other eco-sensitive aspects in the area.

Shrimp farms still a threat

In the last two-and-a-half decades, shrimp farming in Villupuram has increased a great deal, according to officials and villagers. Since then, water quality has dropped. The NGT, based on a petition filed by Tamil Annai Thamarabharani Welfare Trust in 2015 against unauthorised shrimp farms and hatcheries functioning in and around Nadukuppam village in Marakkanam, ordered the authorities to cut off power supply to shrimp farms and demolish them, except the 30 to 40 farms that had valid licences. The NGT also directed the authorities to ensure that agricultural land, salt pans, mangroves, wetlands, forestland and land for public purposes shall not be used for construction of aquaculture farms. Following the order, the Forest Department took up a massive encroachment eviction drive and shut 90 illegal shrimp farms on forestland. “Right now, there are no shrimp farms in the forest area and the sanctuary. There are some on patta land,” says Sumesh Soman, District Forest Officer, Villupuram. However, sources say hundreds of aquaculture farms still operate.

Ellama, a resident of Pudupakkam Colony, has 40 cents of land in the village. Around 20 years ago, she says, her family sustained itself through agriculture. But after the shrimp farms arrived, the water got spoiled and she farms only once, after the monsoon. The shrimp farm workers allegedly mix salt with borewell water to make it more saline and discharge the residual liquid into the freshwater stream. Likening shrimp farm owners to “mafias”, an official says there are people who own and operate up to 100 to 200 shrimp farms.

According to the 2016 report, owing to Kazhuveli’s proximity to the East Coast Road, it is under pressure to convert its peripheral areas into resorts. “Another issue is the local community’s dependence for livelihood that has turned into unsustainable resource extraction, and the local community being hostile to intervention by the Forest Department, which is seen as a threat to many illegal prawn farms operating in the area. Hundreds of hectares of reed beds were dredged to create a prawn farm inside the core wetland in the summer of 2014, due to which thousands of waterfowl may lose their wintering habitat,” it says.

What next?

Through field observations from 2002 to 2005, two researchers from the Pitchandikulam Bioresource Centre published a paper on the species diversity of the Kazhuveli watershed region in the Zoos’ Print journal. They found at least 268 vertebrates and termed the wetland “an area of immense importance from the standpoint of natural history and potential towards conservation”. Taking note of the ebb and flow of fishes, they said, “If only the wetland can be provided adequate protection from encroachment and poaching, the natural dynamism of the late 80s and early 90s could easily reassert itself.”

When the project started, it was reportedly said sluice gates in the check dam would be opened to let seawater in. But the check dam is constructed above the sea level, and there is no way seawater can flow in during high tides, the PWD official confirms. Mr. Reddy told The Hindu on September 28 that clearance for the bund was still pending with the Forest Department. “We’ve asked them to modify the plan...to let seawater in,” he said.

“The way forward is for departments to sit down, rope in an institution like IIT-M, and do a technical assessment to figure out a balance to provide drinking water to villages and also let seawater in to protect the ecosystem,” says Supriya Sahu, Additional Chief Secretary, Departments of Environment, Climate Change and Forests.