For the last few weeks, the Webb Space Telescope has treated us to breathtaking views of the distant universe. But in the latest photos, Webb focuses on wonders much closer to home: Jupiter, with its delicate rings, gargantuan aurorae, and monstrous storms.

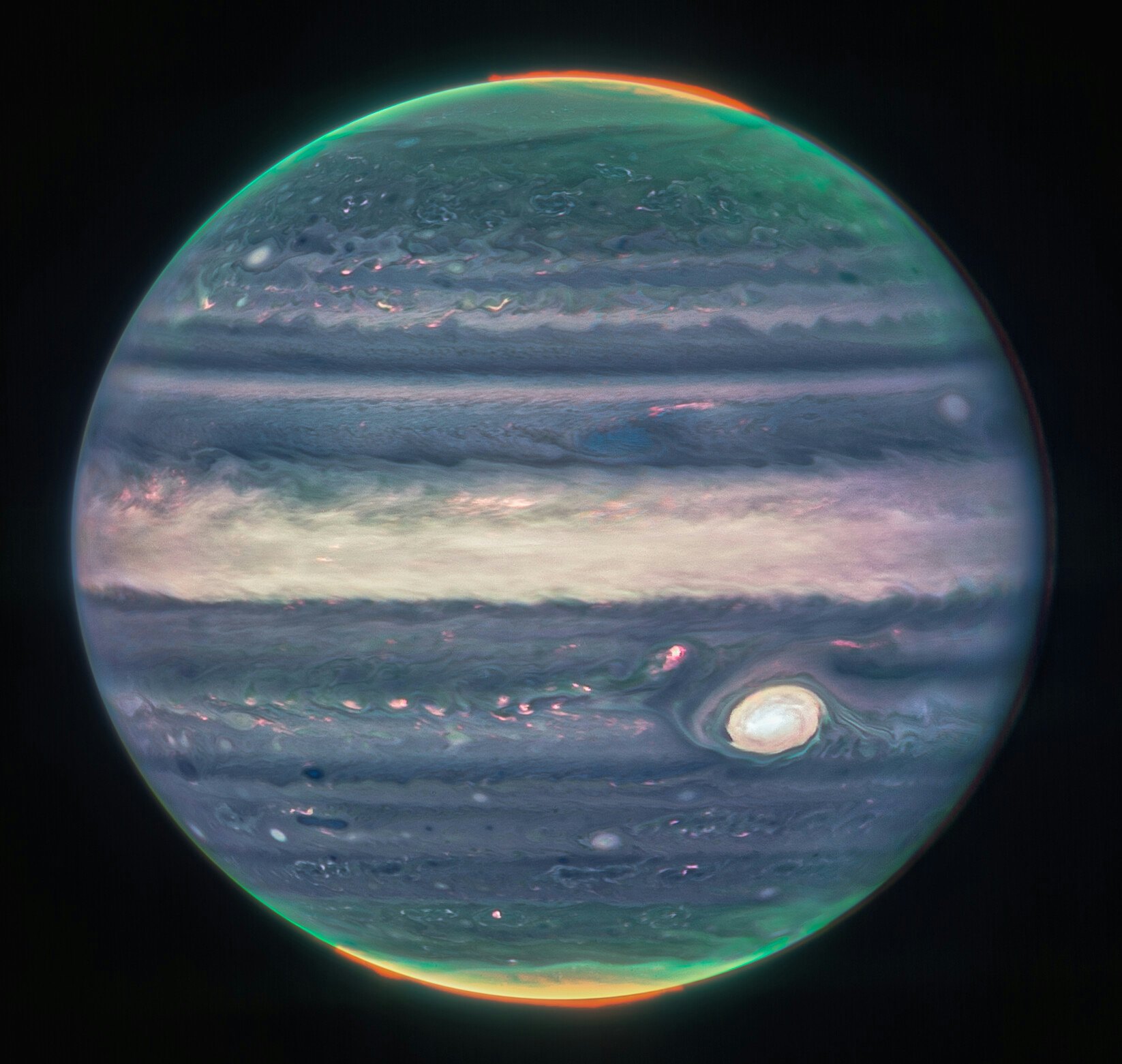

We're used to seeing Jupiter in warm colors, but in these newly-released images, it appears pale and ghostly. Webb's NIRCam instrument photographed Jupiter in infrared light, which human eyes can't see, so researchers mapped each infrared wavelength to a corresponding visible color. Longer wavelengths translate to shades of red, while shorter ones convert to blues. In this close-up view of the gas giant, the polar aurorae are blazes of red.

Jupiter's aurorae are huge versions of the phenomenon that creates both the Northern and Southern Lights here on Earth. When a solar storm strikes a planet, streams of electrons pelt the planet's atmosphere, energizing molecules there. Those molecules release that extra energy as light, creating dancing streamers of light in the sky. Jupiter's version could swallow up our entire planet.

Beneath the immense glow of Jupiter's aurorae, the upper atmosphere around Jupiter's poles is hazy, reflecting light in wavelengths that translate to greens and yellows in the composite image. Other clouds, deeper in the planet's atmosphere, show up in shades of blue. And the iconic Great Red Spot, a gargantuan storm just south of Jupiter's equator, reflects sunlight so brightly that it glows white.

The image you see is actually a composite of several images taken with NIRCam, using all three of the instrument's infrared filters to focus on different wavelengths of light.

"Scientists collaborated with citizen scientist Judy Schmidt to translate the Webb data into images," says the ESA in a statement.

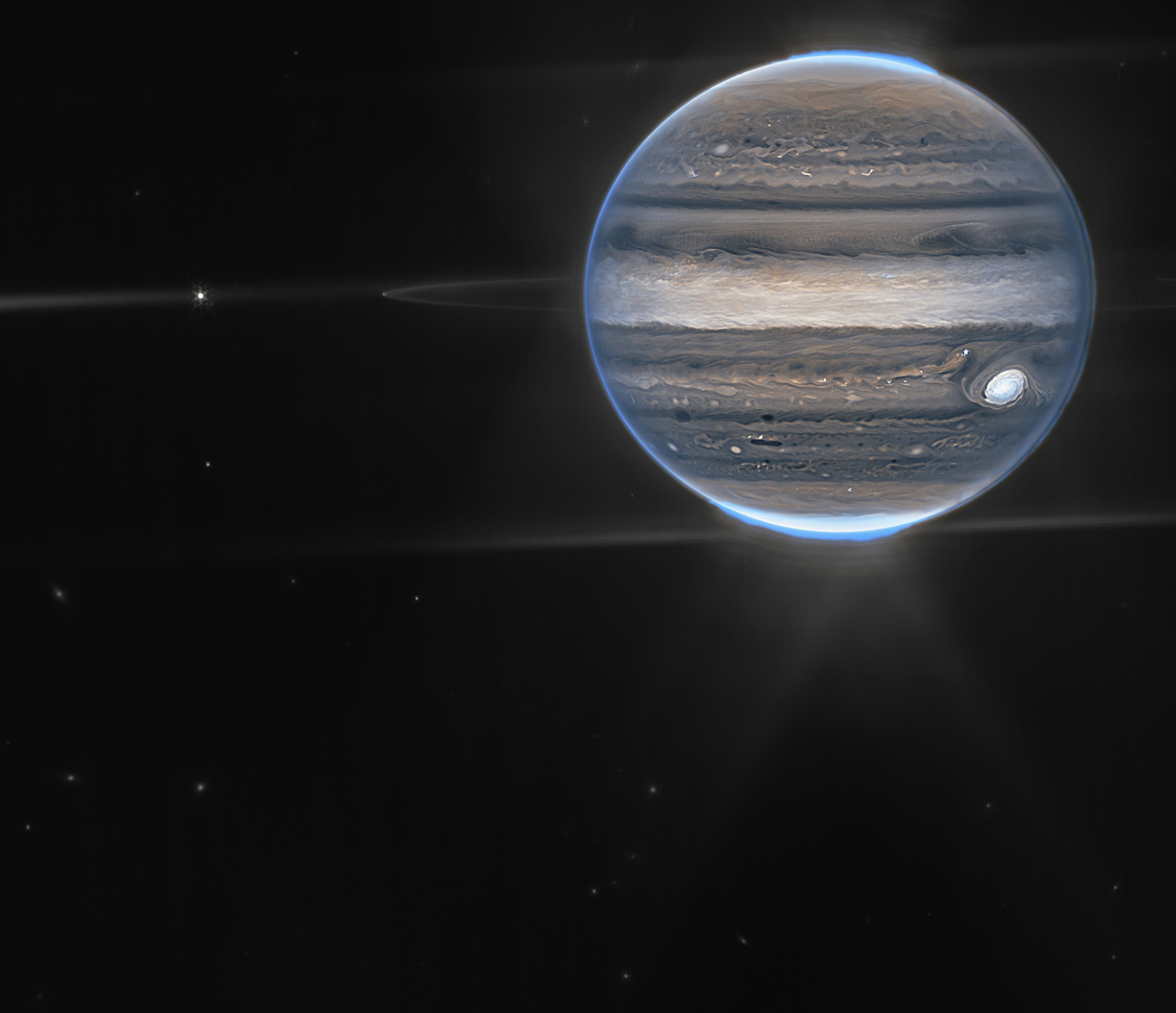

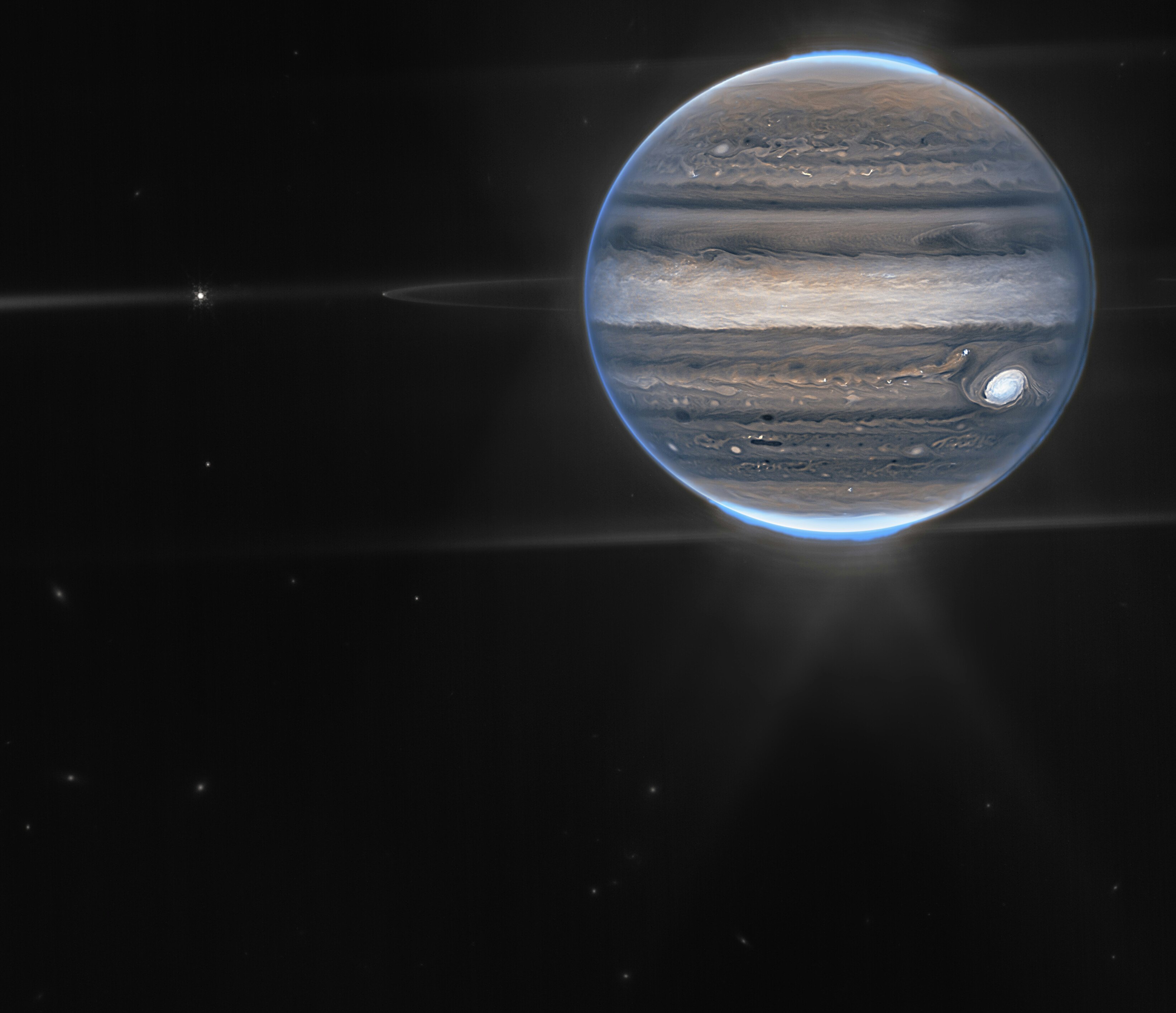

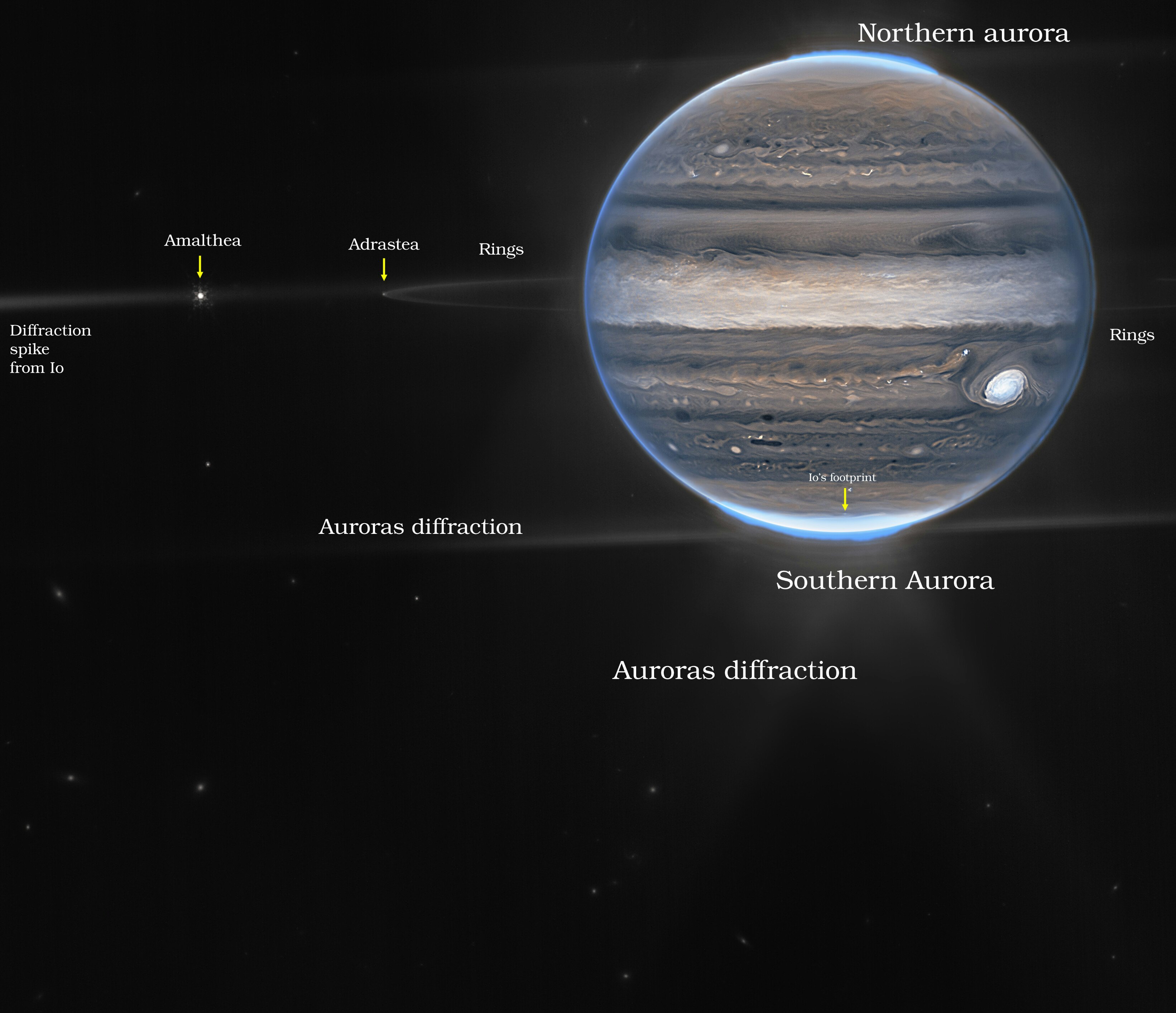

Webb's image processing team combined another set of NIRCam images, using just two of the instrument's filters, into a wider view of Jupiter, its nearly-invisible rings, and two of its small inner moons.

In the image, you can see the faint, delicate lines of Jupiter's rings stretching out to either side of the planet. Imaging Jupiter's rings is no easy feat; they're made of tiny particles that don't reflect much sunlight; as a result, the rings are about a million times fainter than the light reflected from the gas giant itself.

Planetary scientist Imke de Pater and her colleagues plan to study Jupiter's rings in more detail. In particular, they want to understand where the dust that forms the rings actually comes from; it's probably from small moonlets orbiting close to Jupiter. Some of the dust may also come from moons like Adrastea, which shows up as a bright dot at the far left tip of the rings in the Webb wide field image. Even further to the left, a brighter point of light is the moon Amalthea, an oddly-shaped reddish ball of ice and minerals.

Jupiter's polar aurorae glow bright white at the poles in the wide field image, and the Great Red Spot is another blazing swirl of white light against the darker gray of the rest of the gas giant's upper cloud layers.

But Webb can't help looking toward the farthest reaches of the universe. According to the ESA, "The fuzzy spots in the lower background are likely galaxies 'photobombing' this Jovian view."