Bengaluru, India – In early March, a realistic AI-generated image of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, styled as Bhishma Pitamah from the ancient Hindu epic Mahabharata, was boosted as a political advertisement on Instagram.

With long wavy grey hair, a sun-shaped mark on his forehead and donning body armour, the image depicted what Modi fans see as his role in today’s world: a reincarnation of supreme commander Bhishma who fought against foreign threats.

This Instagram image, created by the right-wing page Hokage Modi Sama and first posted in 2023, was boosted as a political advertisement for two days in March, garnering more than 35,000 impressions.

An Al Jazeera review of Meta Ad Library data of political advertisements in India over the past three months revealed that, between February 27 and March 21, Hokage Modi Sama promoted nearly 50 pieces of AI-generated images of Modi, making it the leading advertiser of AI-generated Modi images on Instagram.

The Meta Ad Library is a public archive that hosts a collection of political advertisements run on its platforms, which include Instagram and Facebook.

The common theme across all the images shared by the handle was the valorisation of Modi as a Hindu leader. Popular AI images boosted through sponsored posts on Hokage Modi Sama feature Modi as a reincarnation of Bhishma, a suit-wearing son of god, embracing Hindu heritage and the King of Hindu Rashtra settled on his throne, garnering millions of likes and views. (Hindu Rashtra is the contentious ideology of a Hindu-majoritarian rule of India, a move away from its secular founding principle.)

“Through these images, the attempt appears to be to impart a simultaneous sage-like and warrior-like quality to Modi, both of which create the aura of a political leader who is indefatigable, undefeatable, beyond reproach and thus worthy of our unquestioned loyalty,” Amogh Dar Sharma, a lecturer at the University of Oxford who studies political communications, told Al Jazeera.

But the posts by the most prolific online advertiser of Modi’s AI images also show the challenges with enforcing AI-related rules on social media, amid fears of manipulated images being leveraged for propaganda among voters who might not fully understand the extent of alteration that photos and memes could have gone through.

Meta is aware of such use and before a crucial 2024 election year, it announced that starting January, political advertisements on Instagram and Facebook created using artificial intelligence (AI) will have to disclose the use or risk getting banned.

In the 30 days leading up to March 29, Hokage Modi Sama spent 537,799 Indian rupees ($6,500) to boost 363 pieces of political content, including images and videos on its Instagram page, according to Meta Ad Library data. Our analysis shows that nearly 14 percent of all sponsored advertisements, amounting to 50 images, were AI-generated.

All Hokage Modi Sama AI ads were sponsored posts on Instagram and the disclosure of AI’s use was through hashtags such as #aiartwork, #midjourneyart, #midjourneyai and others. Midjourney, which the hashtags appear to refer to, is a popular generative artificial intelligence program.

But Meta told Al Jazeera that hashtags are not an acceptable disclosure for an advertisement which is digitally created or altered. In cases where advertisers need to disclose that their content is digitally created or altered, Meta will add a label that says “Digitally created” near the “Paid for by” disclaimer, including in the Ad Library. Such labels are currently not present on Hokage Modi Sama AI advertisements.

Meta did not answer Al Jazeera’s specific question on whether the photorealistic images advertisements of Modi violated its policy of depicting a real person doing something they did not, or depicting a realistic-looking event that did not happen.

Instead, Meta pointed Al Jazeera’s reporter to a blog post from March 2024 on AI disclosure requirements for advertisers and how the company is preparing for the Indian elections.

Prateek Waghre, the executive director of the India-based Internet Freedom Foundation (IFF), told Al Jazeera that since these particular advertisements are tagged as #aiart, there is a need for content creators to acknowledge the attempt at boosting AI images through some form of disclosure to comply with Meta’s recently updated policies requiring AI disclosure.

AI used to push ‘strategic narratives’

Indian election campaigns have been a vehicle for a slow diffusion of AI-generated images and videos, including through AI resurrections of dead political leaders, and their use as campaign art in official party accounts, as Al Jazeera reported earlier. Despite the threat of AI-generated election misinformation, deepfakes aren’t being exclusively used to deceive voters. Instead, generative AI is being co-opted to build a narrative.

“While disinformation is definitely a serious problem that requires our attention, it also deflects attention from the more subliminal ways in which AI-generated content can help push strategic narratives of political parties,” Sharma of Oxford University told Al Jazeera, after reviewing the AI image advertisements.

“It is not simply that AI is ‘deceiving’ voters into believing something that is blatantly false; rather, AI enables content to be produced that is more creative and that can draw upon more innovative cultural references – this yields political propaganda which is more entertaining and therefore more shareable, which enables widespread circulation” he added.

For instance, the most popular AI image posted by the Hokage Modi Sama page is the “Our Saffron Superhero”. It shows Modi wearing saffron kurta pyjamas, with a flowing cape walking beneath the “Om” flag, a Hindu spiritual symbol. The AI image has nearly two million likes with comments such as, “Who wants India to be a Hindu nation?” in the comments section on Instagram. Most images recast the Indian prime minister as a “saviour”, “saffron-clad guardian of India’s future”, “symbol of Hindu renaissance” and more.

Sharma pointed out that while mythologising political leaders or featuring them in Hindu epics is not new, AI is allowing it to be executed with greater finesse.

“These AI-generated images of Narendra Modi seem to be the latest iteration in a long-running strategy of the BJP to create a cult about [Modi] as a wise and sagacious leader,” Sharma said.

While the Instagram and Facebook pages of Hokage Modi Sama do not have explicit disclaimers on a direct affiliation to Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the page has a history of publishing pro-Hindutva and pro-BJP content. Previously, the page had gained traction after sharing an image of social media platform X’s owner Elon Musk as a Hindu monk, with the caption, “Our fellow bhakt Elon”, denoting Musk as a Hindu nationalist.

Multiple attempts to contact the administrator of Hokage Modi Sama were unsuccessful. In the anime Naruto, “Hokage” is a prestigious title bestowed on a village leader, while Sama is a respectful way to say “sir” in Japanese, so the page roughly means “Leader Modi Sir”. The Instagram handle with 130,000 followers now sells merchandise such as T-shirts, coffee mugs and diaries based on the saffron superhero AI image.

Globally, AI images have been used in political campaigns. In March, supporters of United States presidential candidate Donald Trump’s campaign used fake AI images of him posing with Black voters for “strategic outreach” to the Black community. In Argentina, two presidential hopefuls used AI-generated images to boost their popularity and attack opponents. And in Indonesia, President-elect Prabowo Subianto, the once-feared military dictator, used AI images to rebrand himself as a “cuddly grandpa” on his campaign trail.

In India, in the run-up to the Telangana state elections in December 2023, fact-checking outlet BOOM Live reported that AI images falsely portrayed regional political leader K Chandrashekar Rao at the launch of a free meals scheme for students, which he never attended.

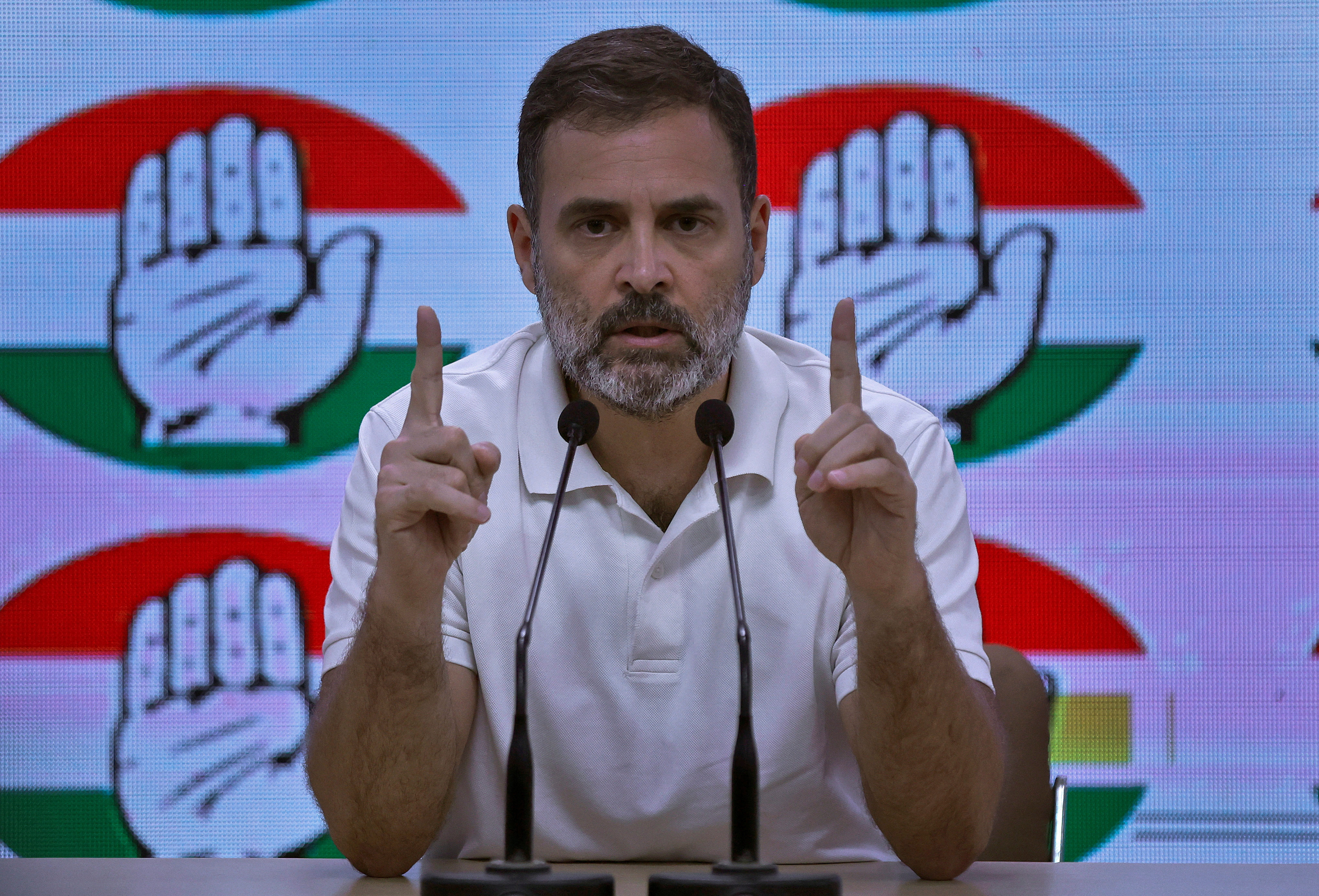

An Al Jazeera review of the Meta Ad Library from December 2023 revealed that the page Mana Telangana shared multiple fake AI images on Instagram and Facebook of Indian opposition leader Rahul Gandhi of the Congress Party posing with children and farmers. Farmers constitute an influential voting block in India and have frequently protested against Modi’s market-friendly agriculture laws.

Gandhi’s fake image with farmers was accompanied by the caption: “Rahul Gandhi empathizes with farmers, promising unwavering support and a commitment to addressing their concerns individually.” The sponsored post contained the hashtags #aigenerated and #aiimages, indicating they were AI-generated, and had an estimated 7,000 impressions.

West vs Global South

There is also a disparity in the way platforms in the West and the Global South are tackling the trend of AI images ahead of elections.

For instance, to mitigate the potential abuse of AI images ahead of the November US presidential elections, popular AI image-generator Midjourney banned the creation of fake President Joe Biden and Donald Trump images in March.

But there have been no such steps in India, raising “concern regarding the equitable enforcement of policies by tech platforms across different regions”, Baybars Orsek, the managing director of Logically Facts, told Al Jazeera. Logically Facts is part of Meta’s third-party fact-checking programme, and part of the misinformation combat alliance in India.

Attempts by Al Jazeera to generate AI images on Midjourney of Modi and Gandhi shaking hands were successful, while the prompt to generate an image of Modi and Trump shaking hands resulted in a “Banned Prompt Detected” notification.

“This decision brings to light the disparities in how such moderation policies are applied globally, especially in the context of the Global South, including countries like India, which is heading into the most significant election of the year,” Orsek said.

Al Jazeera emailed Midjourney about the disparity in moderation and is yet to hear back.

It is similar to how social media companies such as Facebook or Twitter policies to keep their platforms safe are skewed towards the West and often neglect perspectives from the Global South, added the IFF’s Waghre.