There are more chickens than any other species of bird on the planet. With three chickens for every human being, they are a food staple for millions of people around the world. But new research shows chickens were domesticated only relatively recently and were once revered.

The question of where chickens come from and how humans have interacted with them over time has eluded us for decades, until now. For many people it is difficult to think of chickens as anything other than food. But two new studies are changing our understanding of human-chicken relationships.

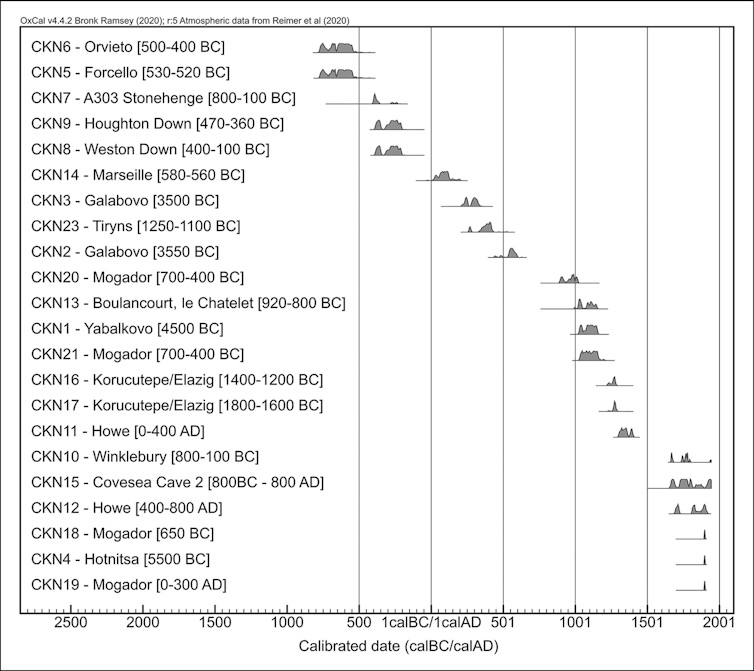

One of our new studies radiocarbon dated bones from 23 of the earliest proposed chickens in Europe and northwest Africa, to test their age. By confirming which chickens are actually ancient we get a clearer insight into when they arrived in these areas and how people interacted with them. Only five specimens corresponded with the dates that archaeologists had previously assigned to them. The other 18 were much more recent than previously thought, sometimes by thousands of years.

Earlier hypotheses, which based their dates on contextual clues such as where these bones had been located and what other artefacts they were found with, suggested that chickens were present in Europe up to 7,000 years ago. But our results show they were not introduced until around 800 BC (2,800 years ago). This reveals that chickens are a rather recent arrival to Europe, compared to domestic cattle, pigs and sheep which reached Britain around 6,000 years ago. The new dating also suggests that in many locations there was a time-lag of several hundred years from when chickens were first introduced to an area, to them really being thought of as food.

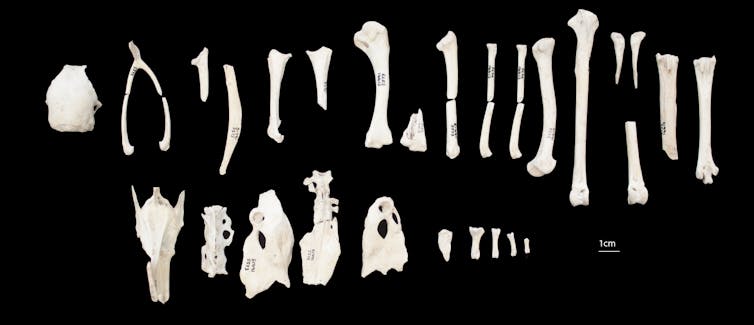

Many of the early chickens identified by our radiocarbon dating are complete or almost complete skeletons. In Britain none of the most ancient skeletons show evidence they were butchered for human consumption. They were often older animals, buried alone in pits. One specimen even had a well-healed leg fracture, indicating human care. She was also still able to lay eggs: she had a substance called medullary bone inside her skeleton which is formed during egg production.

These clues suggest that rather than being considered a source of food, these early arrivals to northern Europe were more likely regarded as special exotica, especially given their small population size at the time.

In some locations shortly after chickens were introduced, we find them buried with humans. A new survey of British Late Iron Age and Roman burials that contained chickens indicates these burial rites were often gendered: males were buried with cockerels and females with hens. Chickens may have been included in human graves as “psychopomps”, whose role it was to lead human souls to the afterlife. Such a role would have been in keeping with their association with Mercury (the Roman god of communication and travel). Large quantities of cockerels were sacrificed to Mercury at temples such as Uley, Gloucestershire. In other cases, the chickens in graves were a food offering. This is a practice that became more common in Britain through the Roman period.

It is clear that human-chicken relationships were complex and about more than just food for quite some time, even after they started to venture onto the dinner table.

So where did these special birds first come from?

From the jungle to the fields

Recent DNA analyses confirmed chickens were domesticated from a subspecies of red jungle fowl called Gallus gallus spadiceus which lived in south or south-east Asia. This would imply chickens were domesticated within this broad region.

Before now, there were three main hypotheses on location and timing. The first places domestication around 4,000 years ago in the Indus Valley. The second argues it happened in south-east Asia well over 8,000 years ago. The third sees their origins in northern China 10,000 years ago.

But these theories fail to take into account crucial factors. These include: dating uncertainties, skeletal similarities between chickens and other local wild species, and the broader cultural and environmental context.

In the second new study our team reassessed the identification of the species, the domestic status and the dating of the most ancient reported chicken bones from more than 600 archaeological sites across 89 countries, in four continents. We found all three hypotheses are wrong. The oldest bones now confidently assigned to domestic chickens come from the Neolithic site of Ban Non Wat in central Thailand, and date to around 3,500 years ago – much later than previously thought.

While uncertainty remains about why chickens were domesticated, one thing appears to have drawn chickens and people together: rice. The introduction of dry rice farming in central Thailand coincides with the date of the oldest chicken remains. This suggests the new type of farming may have been a catalyst for the domestication process.

The clearing of the jungle for cereal cultivation would have created a comfortable environment for the red jungle fowl. Simultaneously, the newly grown rice, along with millet, would have drawn the wild jungle fowl into close contact with humans, sparking the domestication process, after which their chicken descendants were dispersed across the world with human societies.

Julia Best was supported by the AHRC (AH/L006979/1 and AH/N004558/1), by the NERC Radiocarbon Facility (NF/2015/2/5). The work was conducted when she was employed by both Cardiff University and Bournemouth University.

Ophélie Lebrasseur is affiliated with the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse, UMR 5288, CNRS/Université Toulouse III Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France, and the Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano, Ministry of Culture, Buenos Aires, Argentina. She receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 895107. Part of the work was conducted when Ophélie Lebrasseur was employed by the University of Oxford, where she was supported by the Arts and HumanitiesResearch Council (grant AH/L006979/1) (2014-2017) and the European Research Council(ERC) starting grant (ERC-2013-StG-337574-UNDEAD) (2017-2018).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.