There’s nothing like a cold beer to cut the summer heat. But have you seen the prices at live events around Chicago this summer?

NASCAR fans paid $63 for a six-pack of Busch Light or Michelob Ultra during the Chicago street race event in July.

The Cubs are charging $28.99 for a 26-ounce “beer bat” memorabilia cup filled with cold lager — a little pick-me-up you might well need to get over how much the cup costs.

White Sox park is tied with five others where fans pay the second-highest beer prices in Major League Baseball — about 69 cents an ounce, or more than $11 for a 16 oz beer — USA Today found.

The Sox and Cubs did not respond to requests for their latest concessions prices.

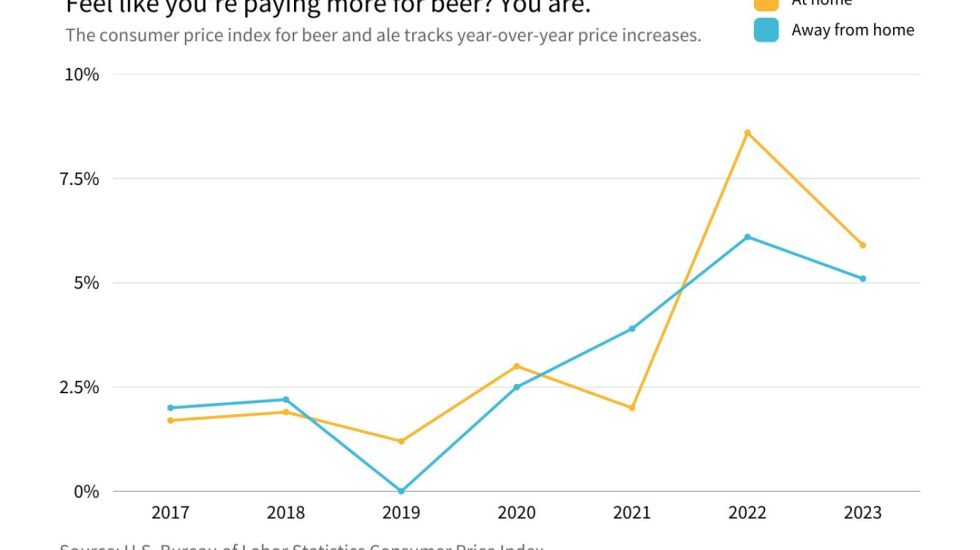

Americans — living with inflation for some time now — haven’t seen beer prices rise as much as food overall. But beer lovers are feeling it now at the height of summer, especially at live, outdoor events. Retailers are charging more, and so are event concessionaires, who have captive audiences — many in those crowds apparently willing to buy a $30 beer bat.

“Beer has not been immune to the inflation we’ve seen in the rest of the economy, though the rates have been lower than a lot of other food products,” says Bart Watson, an economist with the Boulder, Colo.-based Brewers Association, which lobbies for craft breweries.

Watson and other beer industry analyst, attribute the increase to higher prices for wheat, malt, aluminum — for the cans — and shipping and labor.

The average price for domestic beer is up 4.6% in the past 12 months, according to NielsenIQ, the consumer intelligence company.

Long-term, the price of a drink outside your home is more than double what it cost 23 years ago, according to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, which also tracks beer prices.

“The cost of raw ingredients are drastically going up for many things, including beer production, things like hops,” says James Schummer, an economist at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

“That leads to the dilemma of the degree to which the beer manufacturers want to pass that along to customers,” Schummer says. “The challenge for beer manufacturers is: Nobody wants to be the first to pass along these cost increases to the customer because whoever moves first is going to lose some business. On the other hand, they can’t just sit there and eat these losses.”

Higher prices, fewer drinkers

Beer companies have been raising prices though they haven’t been hurting for revenue. At the same time, people are drinking less beer.

Constellation Brands — the maker of beers including Corona and Modelo, which recently passed Bud Light as the most popular beer in the United States — raised prices about 3% to 4%, the company reported in June, according to Dan Su, a beverage analyst for Chicago financial services company Morningstar, Inc. And the company hasn’t lost profit from price increases prior to the most recent uptick, according to its latest financial disclosures.

Price increases at Chicago-headquartered Molson Coors seem to have been enough to get the company through the latest economic headwinds. After raising prices by 10% in two phases last spring and fall, Molson Coors noted in its latest quarterly filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that such boosts helped stave off any losses the company might otherwise have faced due to higher costs.

So perhaps the bigger concern for brewers big and small is that people are drinking less beer. Gaining more market share are canned cocktails, spritzers and malt beverages like White Claw. For which consumers might be getting a better deal: Prices for those haven’t risen as markedly as beer, according to federal data.

In 2022, spirit supplier revenue surpassed beer revenue for the first time in history, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States.

In an era in which most companies are raising prices, beer companies are banking on consumers’ expectations that everything just costs more these days.

It doesn’t have to be that way, says Richard Wolff, an economics professor at the New School of Social Research in New York. Wolff says there are many ways to remain profitable besides raising prices, including improving efficiency and exploring new markets or new marketing campaigns — tactics that companies always are investigating anyway.

“The answer to the question, ‘Why we have inflation,’ has to be that the employers made the decision that their best profit opportunity right now — or at least one of their best profit opportunities — is to jack up the price,” Wolff says.

Pointing to factors outside their control, such as the war in Ukraine’s higher wheat prices or higher costs for malt, energy, transportation and packaging, has mostly worked in companies’ favor.

As a result, beer companies have managed to keep making more money even as beer consumption has tapered off somewhat.

Craft brewers creative

Craft brewers aren’t immune to the economic issues facing beer. At Revolution Brewing, higher costs for ingredients, logistics, packing and everything else are “a huge challenge,” according to Doug Veliky, the Chicago brewery’s marketing head.

“Everybody now has higher costs as part of their business,” Veliky says. “Wages aren’t necessarily keeping up with the cost of beer … and a little less beer is being purchased right now.”

A six-pack of Revolution Brewing’s most popular beer — Anti-Hero IPA — often sells at retailers for about $12. Last year, it cost about $11. Three to four years ago, it was about $9.99, Veliky says.

“We’re still in a great position as a company,” he says. “We have to make sure we’re being extra-considerate about what our consumers are looking for from us. One way to get it all back is to come up with an exciting new beer that blows people’s minds. And that is the real way to do it.”

Revolution is rolling out a new, nonalcoholic sparkling hop water called Super-Zero — aiming to tap into rising interest in seltzers and nonalcoholic beverages.

For many craft beer lovers, specialty brews are worth the higher prices. At a craft beer festival in Lincoln Park in mid-July, people paid $45 to drink all of the beer they could during a two-hour tasting window.

Among them were Elise Brooks, 36, and her husband Patrick Brooks, 40, of Norwood Park. They say they haven’t changed their beer-buying habits just because it’s a little more expensive.

“I wish it made a difference in my life, but it does not,” says Elise Brooks, who works in the service industry. “I will pay it. I will pay to drink what I want to drink. I will never order something I don’t want to drink based on a couple bucks. Maybe I’ll complain a little bit, but I’ll still pay it.”

Within limits anyway.

“We go up $10 bucks, maybe I’ll rethink things,” she says.