Al Albert hopped on top of a table, courtside, surrounded as bedlam threatened far more than his game notes. Even for a member of America’s first family of broadcasting, this marked a first (nearly trampled by a court storming) and a most (ridiculous postgame ever).

Backing up a few hours: He never could have anticipated this. On May 13, 1976, the Nets trailed the Nuggets in a basketball finals series by 22 points late in the third quarter. David Thompson couldn’t stop scoring (42 points). Dan Issel couldn’t stop multitasking (30 points, 20 rebounds). The Nets led the series, 3–2. But it seemed likely, nearly certain, that Denver would force a Game 7 back home in Colorado.

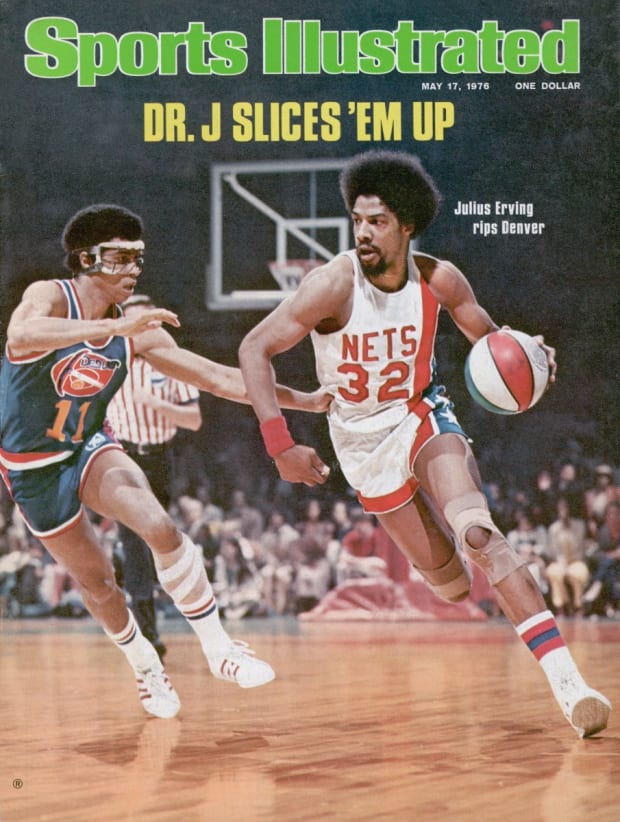

Likely? Near certain? O.K., said Dr. J. The Nets’ star, Julius Erving, took over (31 points, 19 rebounds, five assists, five steals and four blocks in 45 minutes), while three teammates reached double figures to erase the deficit and net the championship with a 112–106 triumph. This wasn’t the NBA title, by the way. It was for the American Basketball Association crown. And, on a historic night, no less: This would become the final game ever played in the ABA.

Malcolm Emmons/USA TODAY Sports

Hence the bedlam. The final horn sounded. The Nets, then a “New York” franchise and operating out of Nassau Coliseum in Long Island, were euphoric, and their fans even more so. Al was based in Denver, the voice of the Nuggets, and, while set up at that courtside table, the celebration engulfed him. “Fans stampeded through the press table like wild horses,” says his younger brother, Steve. “And, in the process, they absolutely obliterated everything.” They stripped Al of his headset and microphone; severed phone lines, cable lines; dragged his television monitor to the ground and stomped all over it. Those notes? Vaporized, Steve says.

Steve doesn’t stifle a laugh now, with Denver back in another final series, for the first time in a long time. But that night, now almost 50 years ago, he studied the chaos with concern. He saw Al standing on top of that table, seeking refuge. His brother’s facial expression landed somewhere between confused and helpless. At that moment, a smaller slice of basketball history—two brothers calling a finals series, with Steve calling the Nets games—mattered little. Safety mattered more.

“Out of respect for the hometown announcer, I guess, wave after wave of people circumvented my end of the broadcast table,” Steve says. “Thankfully, they went clear around it.”

He’s really laughing now, over the phone Monday. It’s not often that two broadcasters from the same family end up calling the same game, let alone one of impossibly high magnitude, and not on the same side (as in childhood) but the opposite one (as adults). Rarer still with a near trampling. Rarer even still for the final game of a professional sports league. It must be some sort of first.

It’s not like their lives, while based in the same profession, pointed either Al or Steve toward that precise moment. Steve was in his first season calling ABA games, after moving back to New York from Cleveland, where he worked hockey broadcasts. Al had been the voice of the Nets, of all things, before the Nuggets enticed him West. That season, 1976, marked his first in Denver. New York, meanwhile, didn’t look beyond the Albert family dinner table to replace him.

Facing the court, Steve sat at the far left end of the broadcast table. Al settled into the same spot, but on the far right. This wasn’t a movie, but it sure felt significant to the brothers. Man, Steve thought before tip-off, we used to do this for Ping-Pong at age 9. They were still kids, after all, which layered additional meaning.

That went for the Nuggets, too, as a franchise. Until this season, that game marked the franchise’s last in a finals in either the ABA or NBA. That season was supposed to be their season. Denver led the league with 60 victories. It fought through a physical seven-game series with Kentucky to reach the semifinals, then won another series, also in seven, over San Antonio. The Nuggets were coached by a native New Yorker in Larry Brown and his wise-cracking sidekick in Doug Moe. Thompson won Rookie of the Year honors. They had everything and everyone they needed—except for two elusive finals wins and maybe the energy sapped from two long, tough series before the finals.

“Seems like a pretty long time ago,” Steve says. “Makes for a nice little sidebar.”

It’s more than that, though. Back up a few decades: The Alberts were New Yorkers, born in Brooklyn, bred in N.Y.C. sports. Marv was the oldest, then Al, then Steve. They grew up playing roller hockey together on their street and impersonating wrestlers in their bedrooms, while stuffing pillows down shirts and bouncing up and down on beds.

Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated

They also, oddly, shared the same exact ambition—and from the earliest of ages. Their parents thought (hoped?) it was a phase, this shared dream of we’re all going to be broadcasters. They’d lock themselves in a small room adjacent to the living room at night, turn down the volume on whatever game happened to be on television (Yankees, Dodgers, Giants), then announce the action themselves. The brothers taped on a VHS recorder, the big, bulky machine with reel-to-reel tapes. They switched roles all the time: One brother did play-by-play at the end of the game … another controlled the crowd and sound effects records … the third simulated things like the crack of a bat, using two marking pencils their father purchased in bulk at the nearest grocery store. His boys broke them all the time.

Marv became their ringleader, the teacher of the Albert School of Broadcasting. Soon, they started calling Ping-Pong matches. Yes, table tennis, which they played in the family basement, often driving their parents to justifiably complain. But this wasn’t what their mother hoped—a passing fancy, she often called their shared ambition, wishing they’d turn to stethoscopes over microphones. And then, with Al and Steve early into their actual, bona fide professional careers, “here we were,” Steve says, “announcing against each other in the ABA championship.”

In the years between that finals series and this one, all three brothers called all manner of sports (NBA, NHL, pro boxing, NFL, college hoops). But two Albert brothers never had a night quite like that one.

Same went for the Nuggets. They moved from the ABA to the NBA the next season, and, in the nearly half a century between finals appearances, advanced to the playoffs 28 times—and lost in the first or second round in 24 of those postseasons. But while nobody will mistake Nuggets fans for Broncos ones, Steve believes that this season—and this series—are reminding everyone outside of Colorado that professional basketball fandom exists in Denver. Always has, as evidenced by Al’s career, 21 years of which he spent courtside, calling Nuggets contests. “He was beloved,” Steve says.

Denver’s first NBA finals came far later than for its ABA brethren, which also moved over (Indiana, San Antonio and the New York–New Jersey–now–Brooklyn Nets). Steve is asked whether Miami’s comeback in Game 2, which started with a 15-point deficit, reminded him of that long-ago night when the Alberts made a slice of history within a larger slice of history. Sort of. But not quite.

After all, the 1976 game marked the series finale. Al never got to sign off on the franchise’s final ABA affair, as the telecast was taken off the air. Neither ever called an ender quite like that one. Asked what he might tell anyone who settles into their seat at the broadcast table for this series finale—imagine if Denver wins, in Denver, after everything—Steve says, simply, hold on to your hat, keep the headset on and maybe nail your notes to the table.