SPOILER WARNING: The following article gives away just about all of the most important details from Beau Is Afraid, so unless you have taken part in this perplexing journey, act like our title character and try really, really hard to be careful.

Personally, I am convinced that there is not a more unique, ambitious, and demented (a term I use admirably here) voice in horror cinema working today than Ari Aster. The filmmaker made his feature-length debut with a thriller that was quickly regarded by many as one of the best horror movies ever made in 2018’s Hereditary, which he followed up just a year later with the nearly as unsettling Midsommar. However, while his latest feature-length effort, Beau Is Afraid, is certainly disturbing enough to count as a “horror movie,” calling it so may be doing it a disservice.

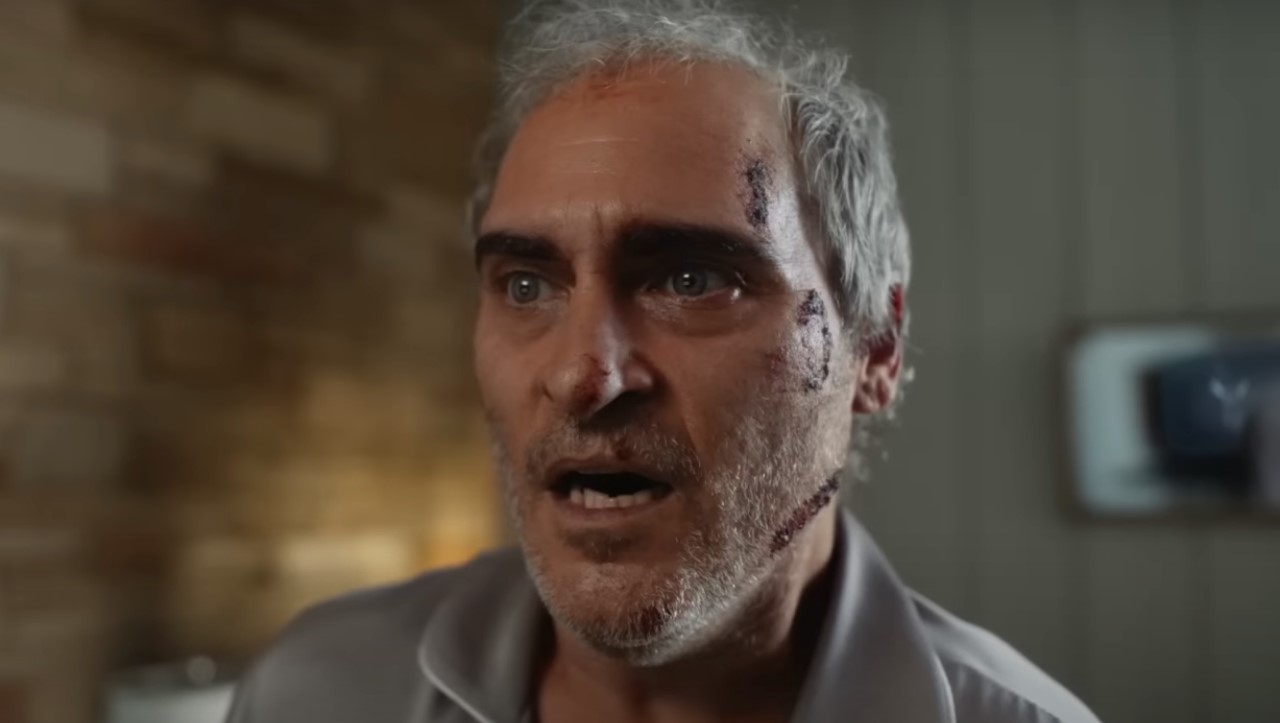

The movie is many things: a commentary on existential dread exaggerated to nearly apocalyptic proportions, a surreal fantasy adventure on par with The Wizard of Oz in terms of visual scope, a three-hour, psychedelic panic attack, etc. At its core, however, it is the story of a deeply neurotic, middle-aged hypochondriac (Academy Award winner Joaquin Phoenix, in one of his most demanding performances yet) and his relentlessly terrifying, absurdly surreal, ongoing struggle to travel to his mother’s house. Does he finally make it to his destination? What becomes of our damaged hero? And what the hell does it all mean? Read on as we attempt to explain the Beau Is Afraid ending as best we can, starting with a basic breakdown of the final act.

What Happens At The End Of Beau Is Afraid?

When Beau Wassermann finally makes it to his destination, the funeral for his extravagantly wealthy mother, Mona (portrayed in her younger years by Zoe Lister-Jones), has already ended, but he learns he is not the only guest who arrived late when the woman he fell in love with as a teen, Elaine Bray (played here by Parker Posey and in flashbacks by Julia Antonelli), shows up. The reunited pair go up to Mona’s bedroom to have sex to Mariah Carey’s “Aways Be My Baby” and, all the while, Beau fears that this sexual encounter (his first) will kill him, just like how his father died at the moment his conception, as his mother claimed. However, it is Elaine who dies by the end, at which point Beau discovers his mother (Tony winner Patti LuPone) is alive and saw the whole thing.

The ensuing conversation between the fractured mother and son could be better described as a scornful onslaught of coldly unsympathetic remarks toward Beau, intensified by a series of heart wrenching reveals. For starters, like most of the characters Beau encountered throughout his journey, his therapist (Stephen McKinley Henderson) is Mona’s employee and their sessions were merely her way of keeping tabs on him. He then learns that a recurring dream involving his mother locking a boy up in her attic is actually a memory of the last time he saw his brother and also hidden up there is his real, live father: a giant penis-shaped monster. Yet, the most devastating reveal is Mona’s long-standing, deep-seated hatred for her son, which compels Beau to strangle his mother, supposedly, to death.

Traumatized by his actions, Beau runs out of the house and finds a motorboat that he takes out into the water and, unwittingly, right into a stadium where his mother (a master at faking her death, apparently) puts him on trial for his selfish, traitorous acts against her. Unfairly unable to defend himself against video evidence that twists key moments from the film against his favor, Beau has no choice but to wistfully reflect on his somber existence before succumbing to his boat’s loudly malfunctioning motor as it reaches the point of explosion.

The Final Act (And Entire Film) Is An Epic Meditation On Guilt

Throughout Aster’s filmography so far (including his short films) lie themes of dysfunctional relationships and psychological manipulation. Hereditary chronicles a family’s destruction in the wake of tragedy, but is revealed to be all part of a demonic cult’s planning, and Midsommar (which Aster based on his own experience with a break-up) sees Dani (Florence Pugh) and Chrisitian’s (Jack Reynor) one-sided relationship reach its tumultuous peak as they and their friends insidiously fall prey to a deadly cult. Beau Is Afraid is, arguably, the strongest example of these themes in an Aster film, but with the major differentiator being the inclusion of guilt as a major factor.

As we come to realize, Mona has been treating Beau as her puppet since the beginning, ruling over every aspect of his life — from his decrepit apartment building, which she owns, to the people he interacts with, whom she employs — with painstaking control. To make matters worse, she takes every opportunity she can to subtly (at least, at first, that is) make him feel guilty for merely existing, with the lie that his conception killed his father being the conception of his neuroses. This prevents him from experiencing love and keeps him in a constant fear of death, with the former being a potential cause of the latter from his perspective.

Beau is not even allowed the chance to plead his case, only provided a lawyer whose deliberate lack of a microphone makes him nearly impossible to hear (symbolizing the frustrations of being silenced) and who is publicly killed before he can finish the defense. Furthermore, as Aster reveals in an interview with IndieWire, Beau’s pitiless trial has a certain loosely personal meaning to him. He says his intention with the final sequence is, as we watch Mona clearly derive pleasure from her son’s suffering, to put the audience in her shoes, with Beau serving as Aster's surrogate, as Mona is a metaphorical reflection of the audience judging the filmmaker, or at least the art he has created. That appears to explain why the setting of the final act almost resembles a movie theater.

What Is Real And What Is Fantasy In Beau Is Afraid?

Similar to another recent, experimental thriller, Skinamarink, Beau Is Afraid often feels like a nightmare transferred directly to celluloid for its unsettling atmosphere and bizarre imagery. At times, it begs the question of whether or not what takes place is actually happening or if it is all in Beau’s head.

Honestly, I think you could make the argument the entire movie is just a really, really bad dream because it is highly unlikely that anything we see could happen in reality (Beau’s monstrous, phallic father being the most obvious example). However, I do believe that the film is meant to take place in a reality different from our own and one that allows such otherworldly phenomena to exist.

Yet, if there is one moment that is, undeniably, a product of Beau’s imagination, it is when the play he stumbles onto in the middle of the film curdles into a, mostly, favorable foretelling of his future. If not for its brightly colored landscape, brought to life with wondrously crude animation and theatrical artificial sets, what automatically clues the viewer in to the fact that this is a fantasy is the sight of Beau with a wife, children, and any semblance of hope.

Hopefully, this is breakdown has quenched any curiosity or confusion you have felt over the Beau Is Afraid ending. However, if you are still in the dark about the penis monster, I am afraid we are in the same boat there.