Barbara Walters, who died on Dec. 30 at the age of 93, understood a conversation's most valuable nutrients were in "the juice." That's how she described the texture of an interview, the details that didn't necessarily relate to harder questions we expected her to pose to famous people but told us a lot about them.

Only Walters knew how to obtain that nectar in a way that made consuming her interviews feel essential in a broadcast news industry dominated and ruled by men. "'The most important thing is only the hard news question,'" she recalls her colleagues insisting in a 2014 "Oprah Winfrey's Master Class" video. "I don't think so. I think it's important to know what's important to them."

In this context, she's referring to the American presidents she's interviewed, which includes every single one starting with Richard Nixon and ending with Barack Obama. She also interviewed Donald Trump in a 1990 episode of "20/20" as part of a promotional tour for his book "Surviving At The Top," before he entered political life.

Relative to other men whose reputations Walters caved in on national TV, Trump was easy game.

Sometimes, Walters would leap right to the squeeze. Trump likely assumed prime time's queen of the Gaussian blurred focus would buy the illusion of opulence and success he was selling. Who was Barbara Walters, after all, other than a woman albeit one famous enough to pay attention to but, in the end, a mark like all the rest? Maybe that's why he opened their 1990 interview with a babbling brook of bilge about how dishonest the press is.

"Well, as a member of the press, let me try to clear up some of the things which you say aren't true," she calmly responds, cracking open his book. "'My bankers and I worked out a terrific deal that allows me to come out stronger than ever. I see the deal as a great victory,'" she reads. Then she looks up from the page. "Being on the verge of bankruptcy, being bailed out by the banks –" she says.

"Well, you don't have to say it like that," Trump weakly blurts before Walters holds up her hand and continues the savaging: "Skating on thin ice, and almost drowning? That's a businessman to be admired?"

Trump trying to maintain his cool, says, "You say 'on the verge of bankruptcy,' Barbara, and you talk on the verge, and you listen to what people are saying –"

"I talked to your bankers," she shoots back, rendering him momentarily mute. A beat or two later she adds for good measure, "Several."

Relative to other men whose reputations Walters caved in on national TV, Trump was easy game. In her time and when she was at the height of her powers, Walters coaxed murderers to bare their inner darkness, using similar finesse to lower the guarded egos of celebrities finding themselves in the news for reasons other than their work.

She's chatted with rulers and revolutionaries, beloved legends like Christopher Reeve (for which she won a Peabody) and icons in moments of trouble, like Mike Tyson and Robin Givens, who filed for divorce from Tyson shortly after admitting to Walters, in front of millions, that her husband's temper frightened her. Walters' 1999 one-on-one with Monica Lewinsky at the apex of the sex scandal involving then-president Bill Clinton drew a record-setting 74 million viewers, the most for a TV news telecast on a single network.

Walters' biggest prime time interviews and end-of-the-year lists of "Most Fascinating People," were appointment television because the audience knew Walters would be able to pry details out of them that no other journalists could. And she owed that to her devotion to exploring and exposing something about the personalities of subjects.

Personality-driven coverage is the bane of the hard-news reporter's existence, as it should be, but long before it permeated the industry and made journalists indistinguishable from hosts and fans in the minds of the audience, Walters demonstrated its value.

"You have to find out, if you can, what makes someone tick," she explains in that OWN video, "Because personality does affect history. There has to be ambition there. It can't just be pragmatic. There has to be some idealism."

"Personality does affect history," said Walters

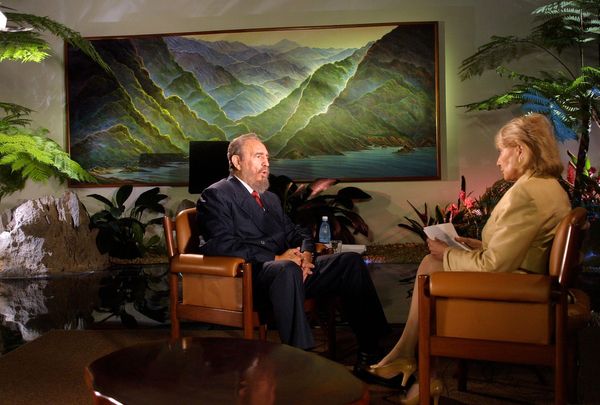

As many colleagues look back on her career in the wake of her death, they've marveled at the fact that her entry into the TV news game was dismissed by her peers as a novelty. This turned to resentment when she began scoring highly sought-after interviews with world leaders, resulting in historic footage of her crossing the Bay of Pigs with Cuban dictator Fidel Castro or delivering the first joint TV interview with Egypt's third president Anwar Sadat and Israel's sixth prime minister Menachem Begin.

In 1985, Walters admitted that she chafed at the memories of watching long, substantive conversations with heads of state boiled down to four or five minutes. "What you get is the news," she said. "But you wouldn't get any of the stuff that made the person a person, or that qualified the statement, or explained it."

That comes from an archived interview by video producer Skip Blumberg fellow critic Matt Zoller Seitz unearthed and draws from throughout his thoughtful remembrance of Walters, in which he points to her fairness as one of her defining strengths.

But Blumberg's film (charmingly titled "Interviews with Interviewers . . . About Interviewing") provides valuable insight into the way she polished the art of the interview, deconstructing how she penetrates the facades of the famous and circumspect. Her preferred tactic was to ask her subjects questions about their childhood, a time of life she observed people speak about with great sensitivity. She found such recollections would open up the people she interviewed. That combination of hard journalism with velvet tactics created an architectural layout for generations of journalists who came after her to follow, for better or worse.

As we were reminded on her final episode of "The View" in 2014, every woman who works or worked in TV journalism owes their career to the barriers and ceilings Walters shattered. In that episode, Winfrey surprised her by appearing on that set and gathering 29 journalists who came in her wake to embrace the retiring pioneer, including Connie Chung, Robin Roberts, Deborah Norville, Meredith Vieira, Tamron Hall, Gayle King, Katie Couric, Savannah Guthrie, Elizabeth Vargas and Diane Sawyer.

All of these women have at some point or another occupied a network anchor chair. But only some ply the style Walters created with some semblance of her skill, if not always or often with the sharp points and jabs with which she used to joust.

Every woman who works or worked in TV journalism owes their career to the barriers and ceilings Walters shattered.

King, meanwhile, employs a similar unflappability and sobriety as Walters did in the face of hostile subjects. Then again, it's one matter to ply that when interviewing politicians or other public figures and another to wield it in the face of strongmen in prime time on broadcast TV, as Walters did with Vladimir Putin in 2001 when asking him to his face if he'd ever had anyone killed.

But NBC's Keir Simmons sparred with Putin in 2021 – not Savannah Guthrie, who proved to be an able match for Trump during his 2020 pre-election Town Hall, where she applied a type of verbal jiujitsu similar to the artful attack Walters used 30 years before. More men are assigned juicy political prime time broadcast interviews these days than women.

Then again, it could be that Putin demanded a male interviewer following Megyn Kelly's match with the Russian authoritarian in 2017 at an International Economic Forum presentation in St. Petersburg. Kelly came at Putin with blunt force, questioning him about the war in Syria and allegations about hacking, leading him to eventually quip, "Maybe someone has a pill that will stop this."

Walters had ways of avoiding such confrontations, explaining to Blumberg that there are smoother ways into obtaining answers to abrasive questions. "I'm sure you're aware that it's been said that . . ." was a favorite side door into hard questions. But if that art became diluted or lost down the road, we can assign many reasons to that with only a few of them connected to Walters' late-career culture-shifting creation, "The View."

In her hard news interviews, she prided herself on conveying a sense of impartiality about her subjects, although off-camera she was notoriously too cozy with politicians and world leaders including, controversially, mass-murdering Syrian dictator Bashar al Assad.

The success of "The View," however, only served to conflate straight information and opinion in the audience's mind, and create a gendered delineation in the news and information space.

Mind you, that is not a sin to be laid expressly at Walters' feet but, rather, a drop in a stream redirecting audiences away from traditional news into partisan cable shows, documentary series, and controlled hybrids of news and entertainment. The Duke and Duchess of Sussex's stateside media debut, which began with Winfrey's CBS interview – the type of "get" Walters once would have taken for granted – is the prime example of this. That begat their Netflix series and Prince Harry's media parade, starting with his upcoming interview with Anderson Cooper on "60 Minutes."

If a person wanted to, they might observe and listen for echoes of Walters' style in Harry's Sunday interview and the others that happen in its wake. But I also hope that instead of merely appreciating the ways that Walters' contributions to the art of conversation will continue, people gauge their success by the bar she set for herself.

"How could you hope to get to know somebody in just an hour?" Blumberg asked her in 1985. Walters confidently replies, "I guess the proof is in what I've done. If you see the interviews, don't you think that you know the people?"