With UK government bonds and sterling both falling hard in recent days, the Bank of England has been forced to step in. Only a few months after it started tightening monetary policy to fight inflation by raising benchmark interest rates and ending its programme to “create” money through quantitative easing (QE), it has made a U-turn.

It plans to create perhaps £65 billion over a two-week period to buy long-dated government bonds to shore up that market, as well as temporarily putting on hold plans to start unwinding its £838 billion of QE money. So will this work?

The specific reason for the intervention appears to be UK pension funds, which suddenly became very vulnerable because of the bonds plunge. This was because pension funds rely on financial schemes known as liability-driven investment strategies or LDIs.

LDIs are essentially an insurance policy to ensure that funds have enough money to pay people’s pensions, even when bonds are paying very low returns. But when bond prices plunged after the government’s mini-budget, funds were forced to find extra money to cover their LDIs. This forced them to sell more bonds and threatened a domino effect where bond prices would keep falling and some funds could have collapsed.

The bank’s intervention has important implications for the wider economy. It comes when people are under increased financial stress because of higher interest rates, climbing energy bills, wages not keeping up with inflation and volatility in the financial markets.

The economy is growing only weakly and may well tip into recession. According to my recent co-authored work, a recession could depress the UK economy for as many as 20 months – longer than the 15 months predicted by the Bank of England.

Stress in the UK markets

These conditions are likely to be an additional reason for the bank’s intervention – despite contradicting its efforts at tightening. Since the interest rates (or yields) on bonds rise as their prices fall, stepping into the market to buy bonds aims to push down these rates.

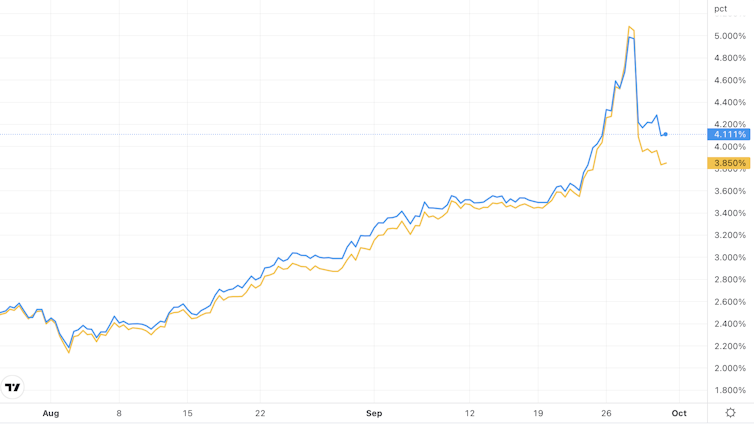

So far it has worked: yields on UK 20-year and 30-year bonds were both north of 5% before the intervention and are now respectively 4.1% and 3.9%. Since the level of these yields sets the tone for borrowing costs in the rest of the economy, this should encourage more consumer spending and business investment.

Yields on 20-year and 30-year UK bonds

The downsides

The bank’s intervention, without even consulting its Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), is a form of what is known as yield curve control. This is a variety of QE in which, instead of just creating a certain amount of money with which to buy bonds, the central bank wants to achieve a specific yield. Such a policy is mainly associated with Japan, where the central bank has been buying bonds to keep yields at very low levels since 2016.

So far the Bank of Japan has achieved its objective, but the yen has lost a lot of value because the bank is having to create more and more money via QE: it now owns some US$3.8 trillion (£3.4 trillion) of Japanese government bonds, over half the total market. Meanwhile, the yen has virtually halved since 2010, and in recent weeks the Bank of Japan had to act to prop it up.

While Japan and the UK’s moves to control bond yields are somewhat different, the Bank of England intervention is also likely to put additional downward pressure on sterling. It is also going to be inflationary. This shows how unappealing the policy options are at present.

The implications

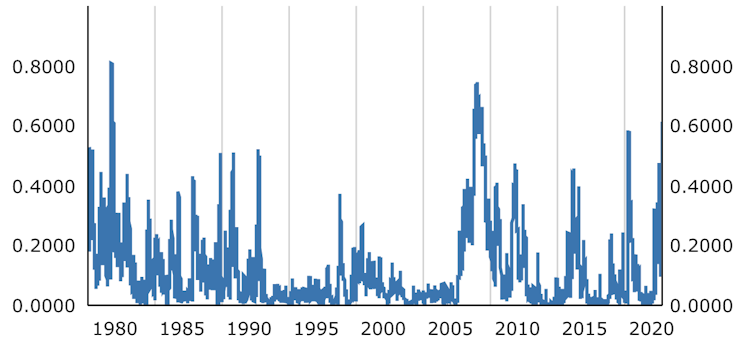

Will the intervention work? The impact of QE on interest rates is the subject of voluminous research. It is difficult to estimate because it depends on the level of the interest rate, as well as the economic conditions. Things are complicated further because central bank studies find QE to be more effective than academic papers do.

But going roughly by the findings in this co-authored paper of mine, an additional £50 billion of QE purchases in the UK might lower bond yields by 12 basis points (0.12 percentage points). That suggests that unless the bank continues with this new scheme far beyond the current October 14 end date, it is unlikely to have much effect.

Moreover, QE partly works by signalling to the markets that it will keep interest rates low for a protracted period. By setting a time limit and also saying that it plans to return to QT in due course, the bank is undermining its new policy.

Also, the credit ratings agencies may well downgrade UK sovereign debt. They usually reduce a country’s credit score when economic policy uncertainty rises significantly, or debt rises to unsustainable levels, or the quality of governance is on the slide.

We’re certainly seeing a big rise in uncertainty. At the same time, the latest World Bank data reveals that in terms of government effectiveness, the UK is down from the top 7% of countries to the top 13% over five years. What remains to be seen is how UK debt will rise, since we currently don’t have official forecasts following the mini-budget.

With no such estimates due to be published until November 23, not to mention the Bank of England’s failure to consult the MPC, the credit ratings agencies will be seriously tempted to downgrade. Such a move would push UK bond yields upwards again, therefore undermining the bank’s intervention.

It’s worth bearing in mind that the main source of the current instability remains the government’s mini-budget and unfunded tax cuts. This is what undermined investor confidence and caused the sell-offs of UK bonds and sterling in the first place, so the best way to reverse this is to tackle the problem at source by the government modifying its plans.

Having said that, such a U-turn would also leave investors very uneasy about economic management. One way or the other, a rocky economic road looks likely until at least the next general election.

Costas Milas has received in the past funding by the Bank of England to work, as the principal investigator, on the project “Liquidity and output growth in the UK”. Costas Milas has received in the past ESRC funding as the principal organiser of an ESRC Seminar Series on Nonlinearities in Economics and Finance.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.