This week’s landmark report on the impact of invasive alien species revealed costs to the global economy exceeded US$423 billion (A$654 billion) a year in 2019. Costs have at least quadrupled every decade since 1970 and that trend is set to continue.

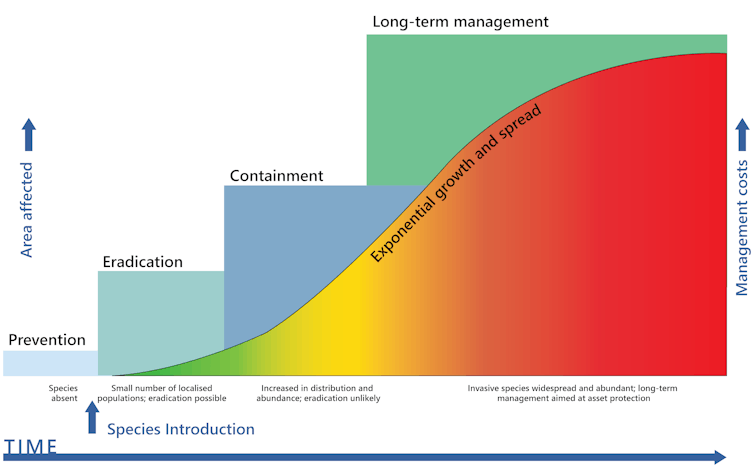

Prevention is better than a cure. Stopping pests and diseases arriving and establishing in Australia is not only better for the environment, it’s much cheaper too.

The biosecurity system is our front line against invasion. Species that pose a significant risk to agriculture have historically received more attention, but we also need to defend our borders against threats to nature.

Here we take a closer look at some pests and diseases we need to keep out at all costs, to protect our biodiversity.

One of the biggest threats to biodiversity

Alien species are those deliberately or accidentally introduced to areas where they are not native. If they cause problems, we call them invasive.

Invasive alien species include weeds, feral animals, exotic pests and diseases.

Those that have already arrived have taken a huge toll. Introduced predators were largely responsible for most of Australia’s mammal extinctions. And introduced diseases have decimated our frogs.

Invasive species are pushing most (82%) of Australia’s 1,914 nationally listed threatened species closer to extinction.

Imagine if those invasive species had been kept out of Australia. Here are eight of the pests and diseases we really need to keep out.

Read more: 1.7 million foxes, 300 million native animals killed every year: now we know the damage foxes wreak

1. Giant African land snail

Giant African snails have a ferocious appetite. They feed on more than 500 species of plants including agricultural crops and eucalyptus trees. The shells of these giants can be 20cm long and females typically lay 1,200 eggs a year. Adult snails could sneak into shipping containers or machinery and their eggs could be transported in soil or goods. They are now present on Christmas Island.

2. Avian influenza

Avian influenza or bird-flu is a viral disease found in birds. Some strains can kill farmed poultry and susceptible wild birds. Such highly pathogenic strains are thought to have killed millions of wild birds globally in the past few years. The virus can also jump across to mammals, recently knocking off 3,500 sea lions Peru.

Migratory birds could bring the virus here but it could also be carried in imported birds and poultry products, including contaminated eggs, feathers, poultry feed and equipment. Our biosecurity system is responsible for surveillance and early detection, preparedness and management to protect our vulnerable wildlife. In California, preparation includes vaccinating endangered condors.

Read more: Migrating birds could bring lethal avian flu to Australia's vulnerable birds

3. New tramp ants

We’re already battling some species of tramp ants, but there’s more where that came from - there are at least 16 different species. So far six species including red imported fire ants have been detected, with efforts underway to contain or eradicate them at their incursion points. On Christmas Island, another tramp ant species (yellow crazy ants) formed “super colonies”, killing every animal in their path, including tens of millions of the island’s iconic red and robber crabs. Ants are easily transported to new areas in dirt, plants and cargo. Tramp ants threaten Australian ecosystems, agriculture and human health.

4. Bat white nose syndrome

White nose syndrome is a bat disease caused by a fungus. In less than 20 years it has killed more than five million bats across North America, causing local extinctions and reducing the beneficial services performed by bats such as eating harmful insects. The fungus could be introduced to Australian caves on the shoes, clothing and equipment of people who had previously visited caves in Europe or North America.

5. Crayfish plague

A highly infectious fungal disease, crayfish plague is the main cause of crayfish declines across Europe. It has the potential to devastate Australian freshwater crayfish populations. North American crayfish can be carriers of the disease and the illegal trade of crayfish, such as the dwarf Cajun crayfish for aquariums, also threatens to introduce the disease.

6. New myrtle rust strains

When a strain of myrtle rust arrived in Australia in 2010, it spread quickly along the east coast, infecting 358 different native plant species including eucalypts, bottle brushes and lilly pillies. It has caused major declines and local extinctions of many species. Other exotic myrtle rust strains occur outside Australia. These present serious threats to Australia’s natural environment and to commercial native forest plantations. Importing infected plant material is the main risk of introduction.

7. Savannah cats

Savannah cats are two to three times the size of domestic cats. In 2008 the federal government banned the importation of savannah cats. A scientific assessment found pet savannah cats had the potential to establish and roam across 97% of the country if they escaped or were released. They can take down prey twice as large as feral cats, so 90% of Australia’s native land mammals would be at risk. Demand for the species from the pet trade raises the risk of smuggling or illegal trade.

8. Black spined toad

The black spined toad is potentially more damaging than the cane toad because it could survive across a bigger region including in the colder parts of Australia. It would prey on native frogs and other small animals, be toxic to larger animals, and probably carry exotic parasites or disease. It is a common stowaway in shipping cargo.

Prioritising nature

Australia’s biosecurity system has generally served our country well, but it is under constant and growing strain. Historically, the environment has also been the poor cousin of agriculture at the biosecurity table.

Preparedness and responses for environmental threats remain chronically underfunded, especially when compared to those developed for industry.

A well-resourced independent body focused on the prevention and early elimination of new environmental pests and diseases would be a major step toward achieving our global commitments to end extinction.

Jaana Dielenberg is based at The University of Melbourne and works for the Biodiversity Council. She is a member of Invertebrates Australia and the Ecological Society of Australia. She previously worked for the now ended Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the Australian Government's National Environmental Science Program. She thanks James Trezise for his contribution to this article.

Patrick O'Connor receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Australian and State Governments. He is a councilor on the Biodiversity Council and affiliated with the Nature Conservation Society of South Australia and the Australian Landcare movement.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.