Rivers of muddy water from heavy rainfall raced through city streets as thousands of people evacuated homes downhill from California’s wildfire burn scars amid atmospheric river storms drenching the state in early January 2023.

The evacuations at one point included all of Montecito, home to around 8,000 people – and the site of the state’s deadliest mudslide on record exactly five years earlier.

Wildfire burn scars are particularly risky because wildfires strip away vegetation and make the soil hydrophobic – meaning it is less able to absorb water. A downpour on these vulnerable landscapes can quickly erode the ground, and fast-moving water can carry the debris, rocks and mud with it.

With more storms expected through mid-January, officials warned of a risk of debris flows near several recently burned areas, including near Santa Barbara and Los Angeles, Monterey and Santa Cruz counties and the Shasta Trinity National Forest.

I study cascading hazards like this, in which consecutive events lead to human disasters. Studies show climate change is raising the risk of multiple compound disasters, including new research showing increasing risks to energy infrastructure.

When storms hit burn scars

Five years ago, on Jan. 9, 2018, a deadly cascading disaster struck Montecito, a community in the coastal hills near Santa Barbara.

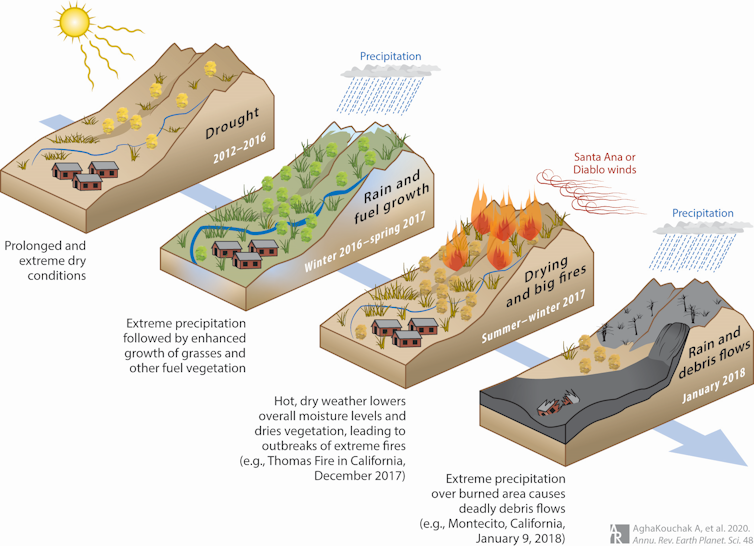

The cascade of events had started many months earlier with a drought, followed by a wet winter that fueled dense growth of vegetation and shrubs. An unusually warm and dry spring and summer followed, and it dried out the vegetation, turning it into fuel ready to burn. That fall, extreme Santa Ana and Diablo winds created the perfect conditions for wildfires.

The Thomas Fire began near Santa Barbara in December 2017 and burned over 280,000 acres. Then, on Jan. 9, 2018, extreme rainfall hit the region – including the burn scar left by the fire. Water raced through the burned landscape above Montecito, eroding the ground and creating the deadliest mudslide-debris flow event in California’s history. More than 400 homes were destroyed in about two hours, and 23 people died.

These kinds of cascading events aren’t unique to California. Australia’s Millennium Drought (1997-2009) also ended with devastating floods that inundated urban areas and breached levees. A study linked some of the levee and dike failures to earlier drought conditions, such as cracks forming because of exposure to heat and dryness.

Individually, they might not have been disasters

When multiple hazards such as droughts, heat waves, wildfires and extreme rainfall interact, human disasters often result.

The individual hazards might not be very extreme on their own, but combined they can become lethal. These types of events are broadly referred to as compound events. For example, a drought and heat wave might hit at the same time. A cascading event involves compound events in succession, like wildfires followed by downpours and mudslides.

With compound and cascading events likely to become more common in a warming world, the ability to prepare for and manage multiple hazards will be increasingly essential.

Climate change intensifies the risk

Several research studies have shown that compound events that include both drought and heat waves have become more severe and frequent in recent years. Studies have also shown that droughts and heat waves increase the likelihood of wildfires. And wildfires can also trigger other cascading hazards, turning otherwise unexceptional events into human disasters.

At the same time, extreme rainfall events are expected to intensify in a warming climate. A warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, leading to wetter storms. This means more burned acres could be exposed to potentially extreme rainfall events in a warmer world.

Cascading hazards are not limited to rain over burned areas. For example, soot and ash deposits on snowpack can increase snowmelt, change the timing of runoff and cause snow-driven flooding.

It’s also important to recognize that human activities and local infrastructure can affect extreme events. Urbanization and deforestation, for example, can intensify flooding and worsen mud or debris flow events and their impacts. That was evident in the videos of muddy water pouring through streets in Santa Barbara County on Jan. 9, 2023.

In a recent study, colleagues and I also looked at the risks to energy infrastructure from cascading disasters involving intense rain over burn areas, focusing on natural gas pipelines and other infrastructure. Our results showed that not only will natural gas infrastructure be increasingly exposed to individual hazards, creating the potential for fires, the chances of cascading hazards are expected to increase substantially in a warming climate.

Managing multiple disasters and climate change

About a year after the devastating Montecito mudslide in 2018, I visited a location where damage to a natural gas pipeline hit by the mudslide led to a fire that burned multiple homes. Looking upstream, I could see many hills next to one another with similar burned scars, slopes and vegetation cover. Each one can be the ground zero for the next human disaster.

Despite the high risk when extreme rainfall and droughts interact, most research in this area focuses on only rainfall or drought, but not both. Different government agencies oversee flood and drought monitoring, warning and management, even though both are extremes of the same hydrological cycle.

Recent disasters and research show a strong need to integrate management and risk reduction strategies of droughts and flood. Having one agency focus on one hazard can have unintended consequences for another hazard. For example, maximizing reservoir storage when expecting a drought can increase the flood risk.

Emergency response has improved since the 2018 Montecito disaster, but it’s clear that communities and government agencies still aren’t fully prepared for the scale and potential impacts of future events.

This article was updated Jan. 10 with the Montecito evacuation lifted. The article is an update to a version published Oct. 24, 2021.

Amir AghaKouchak receives funding from National Science Foundation, NASA, NOAA, Caltrans and the California Energy Commission (CEC).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.