Sometime in our Solar System’s past, a 500-mile-wide ball of rock called 2002 MS4 was peacefully drifting through the Kuiper Belt, minding its own business, when something smashed into its northern hemisphere.

The collision blasted out a crater slightly deeper than — and twice as wide as — the one left by the meteor that killed the dinosaurs here on Earth. Astronomers recently spotted it as they watched the tiny world pass in front of a densely star-spangled background. It’s the first big crater astronomers have ever seen in the remote outer reaches of our Solar System, and it could be a hint that dwarf planets have more eventful pasts than we’ve realized. Federal University of Technology in Brazil astronomer Flavia Rommel and her colleagues recently published their findings in a preprint paper (which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed.)

Little World, Big Crater

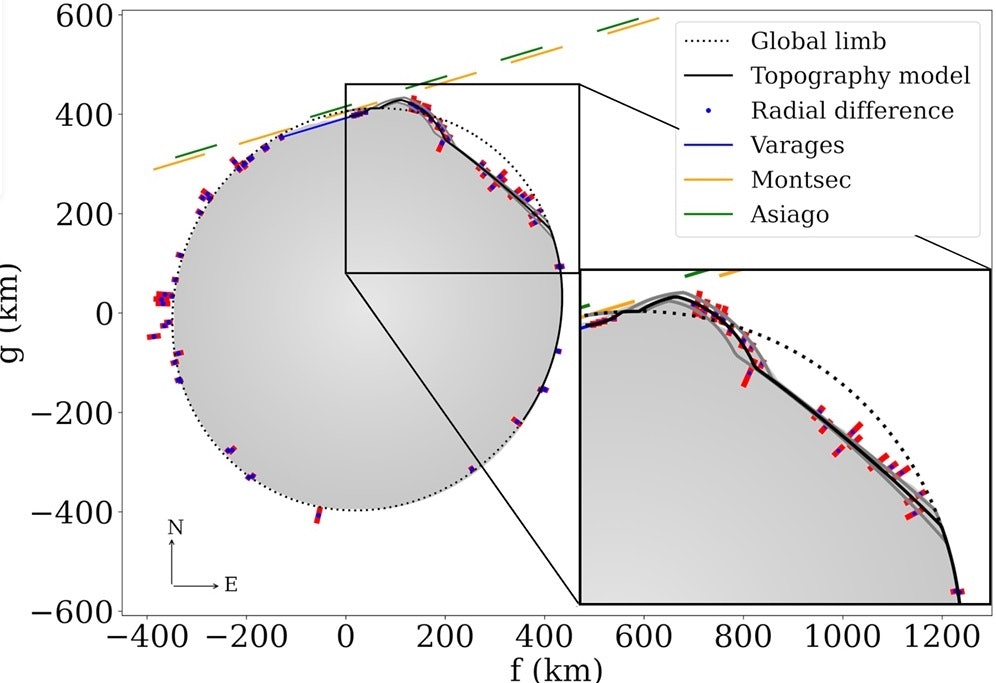

Tiny 2002 MS4 orbits about 42 times farther from the Sun than Earth, in the dim, distant reaches of the Kuiper Belt. Because it’s so small and so far away, it catches and reflects very little sunlight, so even JWST can’t get a detailed look at it. Instead, hundreds of astronomers led by Rommel — some academic and some ordinary citizens — mapped out the shape of the planet by watching its silhouette against the background of stars.

And it turns out that little 2002 MS4 has an enormous dent in one side. Rommel and her colleagues were surprised by that, because big meteor impacts are rare in the sparsely-populated outskirts of the Solar System: There are fewer stray chunks of space rock out there, not to mention fewer things for them to run into. The huge crater on 2002 MS4, in fact, is the only large crater ever discovered beyond Pluto.

The crater’s rim towers 15.5 miles above the dwarf planet’s surface, making it nearly 3 times taller than Mount Everest — and a couple of miles taller than the tallest mountain in the Solar System, Olympus Mons. From that great height, the crater plunges another 28 miles deep into 2002 MS4’s rocky crust. It spreads across nearly 200 miles of the world’s surface; you could fit Vermont and New Hampshire neatly inside it with room left over at the edges.

Astronomers Mike Brown and Chad Trujillo discovered 2002 MS4 during the same survey that found Eris, Sedna, and Quaor (and helped seal Pluto’s fate). But so far, this dented little world is one of the largest objects in our Solar System without a proper name — but it may be one of the most interesting. The rocky, icy objects out in the Kuiper Belt are relics of our Solar System’s distant past, so unraveling the secret histories of worlds like 2002 MS4 might shed light on how planets and star systems form.

.png?w=600)