A newfound population of stars in nearby dwarf galaxies represents the long-sought progenitors of a specific type of stellar death, or supernova, according to new research.

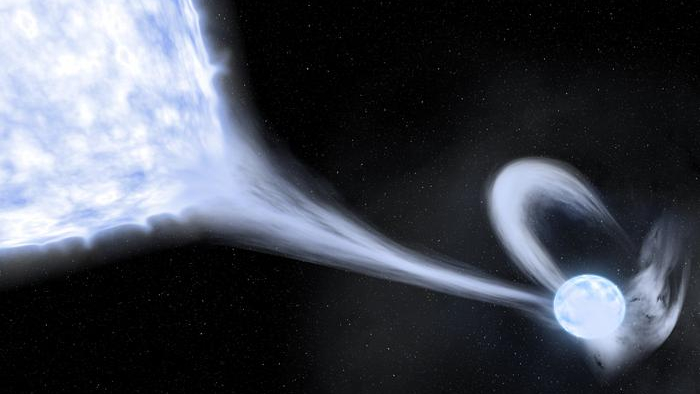

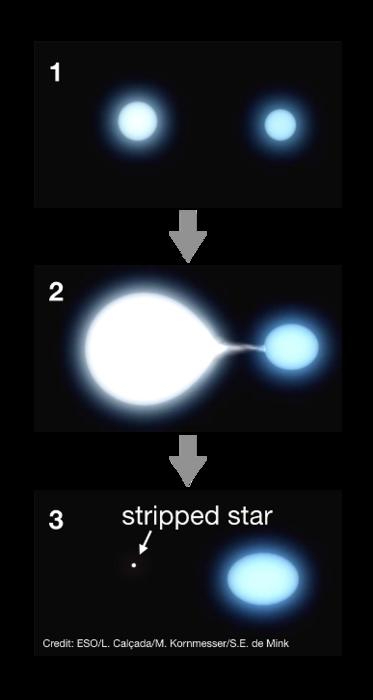

Theories have shown that, for every three massive stars, one is stripped of its outer hydrogen layers across hundreds, or even thousands, of years such that its scorching hot helium core — about 10 times hotter than the sun's surface — gets exposed. So, when these stars die in explosive supernovas, they leave behind hydrogen-poor environments different from other types of supernova events. Despite their theorized abundance, "they were not observed until now," study co-author Ylva Götberg of the Institute of Science and Technology Austria said in a statement.

"This was such a big, glaring hole," study co-author Maria Drout of the University of Toronto said in a different statement. "If it turned out that these stars are rare, then our whole theoretical framework for all these different phenomena is wrong, with implications for supernovas, gravitational waves and the light from distant galaxies."

Related: Astronomers identify 1st twin stars doomed to collide in kilonova explosion

Now, Drout and her colleagues have spotted 25 stars that appear to be stripped of their hydrogen envelopes in the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, two of the Milky Way's closest galactic neighbors. Many of these stars, which are about two to eight times more massive than our sun, are gravitationally bound to another star and form what're known as binary systems. These companion stars were likely responsible for removing hydrogen envelopes of the detected stars, scientists say.

A few stars are also accompanied by a neutron star, which is an ultra-dense remnant of a once-massive star, indicating that the detected system is just one step short of becoming a double neutron star system that would eventually merge, according to the new study.

To arrive at their conclusions, the researchers used data about the brightness of millions of stars collected by the Swift Ultraviolet Optical Telescope. Then, using the Magellan telescopes at Carnegie's Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, the team narrowed the list of candidates to 25 stars which showed unusual UV emissions, hinting at emptied hydrogen envelopes.

While only 25 stars of this missing population have been found so far, "these stars have always been there and there are probably many more out there," said Götberg.

"We must simply come up with ways to find them," she added. "Our work may be one of the first attempts, but there should be other ways possible."

This research is described in a paper published Dec. 14 in the journal Science.