Former President Donald Trump held his first presidential campaign events on Jan. 28, 2023, against the heavy backdrop of four major criminal investigations into his behavior while in and out of office.

In the lead-up to his campaign launch, Trump personally attacked prosecutors and the investigations they are leading as politically biased and a “hoax.”

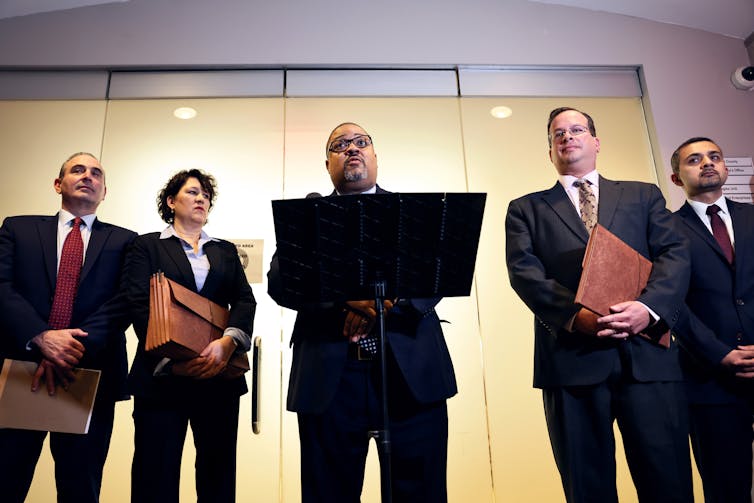

“These prosecutors are vicious, horrible people, they’re racists and they’re very sick, they’re mentally sick. They’re going after me without any protection of my rights by the Supreme Court, or most other courts,” Trump said in January 2022of New York Attorney General Letitia James and Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, both of whom are Black. Bragg is reportedly approaching a decision about whether to charge Trump with illegally paying money to silence porn actress Stormy Daniels about their relationship.

Trump has also called other Black prosecutors investigating him – including Fani Willis, the Fulton County district attorney leading an inquiry into his interference with the 2020 election results in Georgia – “racist.” Willis has said that she requires extensive personal security following death threats from Trump supporters.

This public castigation is helping elevate prosecutors, who typically hold fairly low profiles, into the national spotlight.

The Conversation spoke with Jessica S. Henry, a criminal justice expert at Montclair State University, to help navigate the role of prosecutors and the potential risks of making their positions fair game on the presidential election circuit.

What role do prosecutors serve in the justice system in the US?

Prosecutors are among the most powerful figures in the courthouse. They are the people who decide whether to bring charges, what charges to bring, whether to negotiate a plea bargain and what those terms would be. Very few criminal cases ever go to trial. And so prosecutors wield tremendous power.

Are these posts typically considered political?

Electoral politics have always been part of the backdrop of prosecution. District attorneys – the top prosecutors in a state – are elected in 45 states. And in contested elections, the rhetoric is typically about who is the toughest on crime. Prosecutors who can prove that they’re the toughest typically win. Tough, in these terms, is defined as getting convictions and securing long sentences.

There are examples of prosecutors who used their official position to try to augment their standing in an election. Mike Nifong, for example, was the district attorney in Durham, North Carolina, in 2006, and he was also up for election in a community with a large Black population. Chrystal Magnum, a Black woman, claimed that she had been raped by white lacrosse players at Duke University. Nifong pursued rape charges against these students. But Nifong lied to the media, to the defense and to the courts – and ultimately, the charges against the Duke lacrosse players were dropped. And in a very rare occurrence of accountability for prosecutors who engage in misconduct, Nifong was disbarred.

How have prosecutors become more political in the last few years?

In 2016, about 70% of all prosecutors up for election ran unopposed. In 2022, about 12 of the 30 district attorney election races were considered competitive. So, these are not often contested positions.

And yet, there has been a shift recently, in which people who think that criminal justice can be done differently and done better, choose to run for the head district attorney position. And those with a more reform-oriented agenda – often called progressive prosecutors – have been getting elected around the country. This has brought some really important changes involving who is prosecuted and for what – and also more political opposition from those who want to maintain the status quo.

How does this change the way prosecutors go about their work?

Prosecutors are supposed to be ministers of justice, immune from outside influence, but they’re also people with biases and vulnerabilities. So, when they’ve got high-profile figures like Trump screaming their names out in the national media, it has to increase the pressure on them and how they use their discretion and power. When a case plays out on the national stage, prosecutors may wind up paying attention not only to the specific facts of the case being featured in the spotlight, but also how it is being perceived by their constituents and portrayed by the national and local media.

It can sometimes be deeply problematic when people outside the prosecutor’s office try to dictate prosecutorial decision-making for political gain. In Texas, for instance, lawmakers have proposed a bill that targets prosecutors who refuse to prosecute people who have abortions or parents who seek transgender-affirming medical care for their children. That puts a lot of pressure on prosecutors who are trying to do what they believe is right under the law.

On the flip side, prosecutors are supposed to represent “the people.” So it can be important that the community make its perspective known, such as in the case of police shootings of unarmed people, and the public’s desire for accountability by having prosecutors criminally charge officers for their actions.

In states where prosecutors are elected, they are subject to the same electoral politics as any other elected official. It would be naive to say that prosecutors are completely immune from that external pressure. Of course, we’d like to think that prosecutors, in their commitment to justice, only prosecute cases that are justified and only when there’s enough evidence. But that doesn’t always happen, and sometimes those decisions wind up reflecting local politics rather than the evidence in a particular case.

Do you see that as a risk, potentially, for prosecutors right now?

I don’t know whether we’re going to see attacks on prosecutors as part of a larger trend in national elections. But every time Trump goes after one of these institutional players, like a prosecutor or even a judge, what he’s really doing is destabilizing the public’s ability to trust government institutions.

There is research that shows that the criminal legal system is only as robust and legitimate as the public perceives it to be. While there are many flaws in the criminal system, I believe that personal attacks on prosecutors who pursue criminal charges against Trump ultimately harm our democracy.

Jessica S. Henry does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.