NASA announced Artemis I’s next launch attempts. But the space agency must juggle a few things first.

Last week the space agency tried twice to launch Artemis I from Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Cape Canaveral, Florida. Thousands of people tackled traffic ahead of Labor Day weekend to reach the Space Coast in hopes of witnessing the first heavy-lift Moonshot since the Apollo era. But NASA called off each one, citing a propellant leak, among other issues. The space sector is abuzz with what could happen next. Not just for Artemis I, but for the future of NASA rocketry.

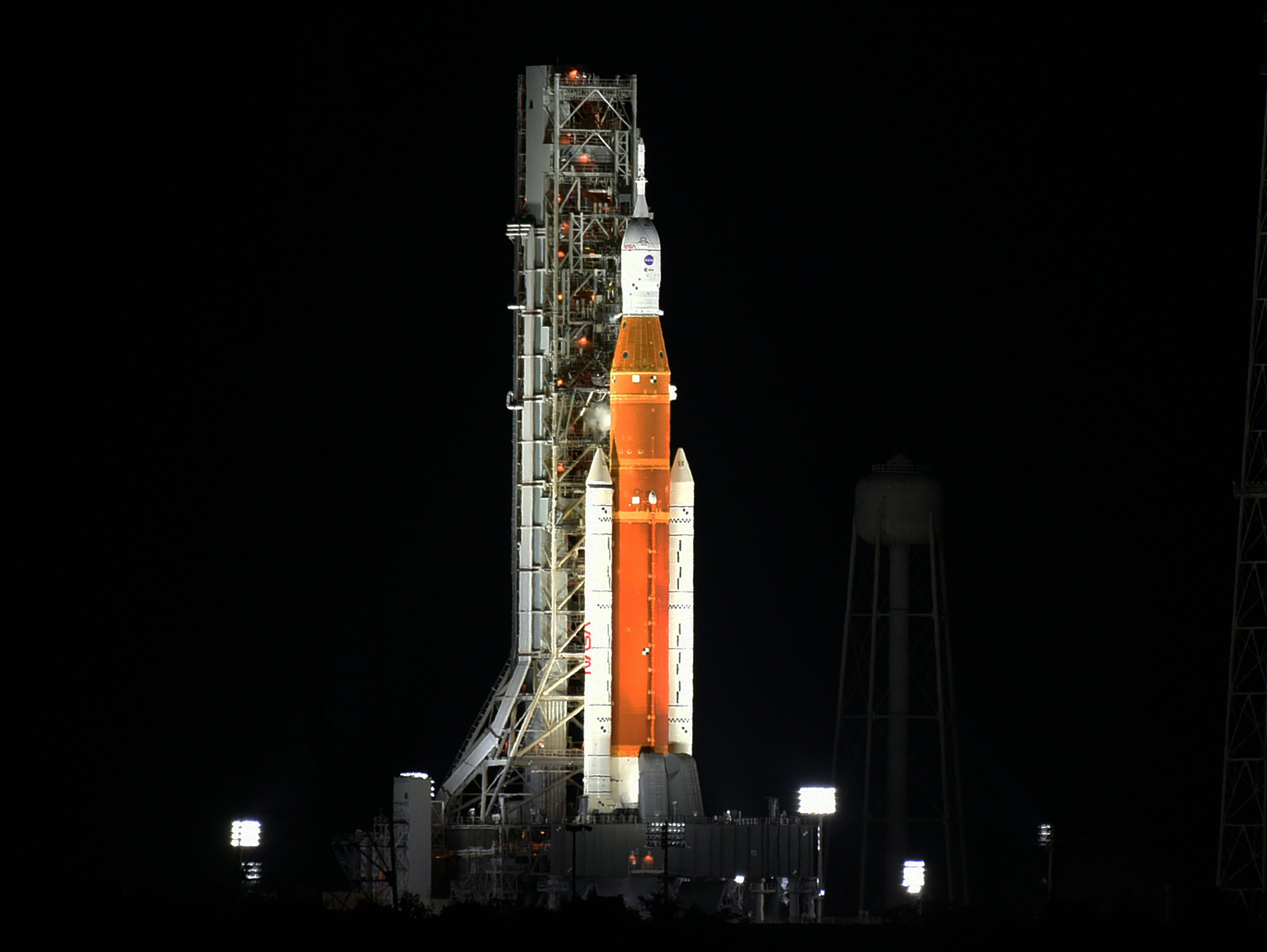

For now, teams work at the launchpad to mitigate the chances of yet another scrubbed launch. The setbacks during both attempts — Monday, August 29, and Saturday, September 3 — come after five months of launch delays, and multiple unfinished wet dress rehearsals. NASA remains optimistic.

These are the next important dates:

- September 17 — short fuel loading demonstration

- September 23 — third launch attempt

- September 27 — fourth launch attempt

If Artemis I gets the green light for either of these days, leadership must work around another key NASA mission, the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), so as to avoid a conflict over use of NASA’s communication infrastructure called the Deep Space Network. These dates shouldn’t be a problem for DART, scheduled to make its most crucial maneuver on September 26.

A fifth tentative launch date is possible, but that depends on the Eastern Range. It’s a collaboration with the U.S. Air Force to monitor and safeguard long-range launchers from harming communities or ships in the ocean underneath a rocket’s flight path.

Jim Free, associate administrator of NASA’s Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate, told reporters on Thursday that “our job is to live up to their requirements.” To pick this third date, Artemis I teams must also coordinate around the next astronaut flight to the space station, Crew 5, on October 3.

Here’s the background — In an unexpected move, NASA chose a date outside of their predetermined list — Saturday, September 3 — to perform the second launch attempt of Artemis I. Multiple dates help safeguard against mild hiccups to launch, like a poor weather forecast.

But NASA has encountered cumbersome problems, like re-emerging liquid hydrogen leaks. Specialists must service these, but this, in turn, prevents Artemis I from being flight ready before certain protocols time out. That meant its final predetermined target date, Monday September 5, was impossible to meet.

The big idea — Three days after Artemis’s first launch attempt, Inverse spoke with Lori Garver, former deputy director of NASA. Her new book, Escaping Gravity, describes her work at the space agency to move it in the direction of more work with the private aerospace sector. Many, like Garver, argue that this invites creative solutions to make spaceflight cheaper and with a quicker turnaround.

Garver and other members of the space sector are concerned by Artemis I’s delays, and what that could indicate about the rocket’s capability.

“Maybe it will launch on Saturday,” she conceded, though that date has now passed. “But we had problems with the green run, we had problems with the wet dress, and these are indicative of a program I think that, again, NASA hasn’t been doing this for over a decade … [and] it’s possible this is related to that.”

Artemis I’s heavy lift base, the Space Launch System, is the source of the mission’s beleaguered status. Garver’s skepticism about the SLS’ design has proven correct, for now.

SLS is designed to throttle the Orion capsule towards the Moon much like the Saturn V. but with repurposed Space Shuttle technology.

Both Garver and Casey Dreier, chief advocate and senior space policy advisor at The Planetary Society, tell Inverse that SLS is at risk of being operationally inefficient. But Dreier also thinks it’s too early to call.

“We simultaneously want NASA to take risks and then critique them when those risks don't pan out,” Dreier says. “I believe NASA deserves some sympathy here.”

“I was watching some old NASA documentaries on the first four Shuttle test flights, which suffered many delays and mistakes, including leaking oxidizer fuel all over the shuttle, gunked-up oil filters, and liquid hydrogen leaks,” he adds. “The big difference there, of course, is the rapidity at which NASA could iterate and learn from each launch. The first ten shuttle launches happened in the space of three years.”

By contrast, Dreier adds, “the first ten SLS launches will take more than a decade! That's a long time to try and discover every edge-case that could impact launch readiness.”

What’s next — Now, NASA must wait until later this month, when Earth and the Moon are once again in a good configuration for a successful roughly month-long mission.

Artemis and Ground Systems teams decided to replace the seals of the quick disconnect that connect the umbilical fuel lines between the mobile launcher (the tower behind Artemis I) and the rocket. They’re doing this at Artemis I’s current home, historic Launch Pad 39B, underneath a plastic, air-conditioned tent workers put up to protect the exposed façade from contamination. This repair work could mitigate the chances of yet another scrubbed launch. NASA will be more confident in it after running a fuel loading test to check for persistent leaks.

Leadership like Mike Bolger, NASA Exploration Ground Systems program manager at KSC, also says NASA will take a “kinder and gentler approach” to loading the ultra-cold fuel into Artemis I in the future to prevent further problems.

In addition to juggling access to the Deep Space Network, the work on the seals, the modified wet dress rehearsal to check these repairs and the constraints of planetary configuration, NASA also has to clear matters up with the Eastern Range.

NASA has filed waivers with the Range over Artemis I’s flight termination system (FTS) batteries, which typically expire after 25 days. If they cannot get these waivers, Artemis I must return to the rocket garage at KSC known as the Vehicle Assembly Building, where they would get reset. The FTS batteries are found across the rocket, John Blevins, SLS chief engineer, told reporters. They’ll be paying special attention to three FTS batteries in the rocket’s core stage, the “real heart of the FTS system.”

Why it matters — A successful Artemis I launch and mission past the Moon and back to Earth will signal the beginning of a new spacefaring era. It will prove that the SLS and Orion capsule is capable of returning to the Moon with a heavy and precious cargo — like a crew and life systems — aboard.

It also closes the first chapter to planting humans on the lunar surface, for Artemis III. Much like Apollo 8’s work, Artemis II will connect these two feats by first taking a crew around the Moon and back.