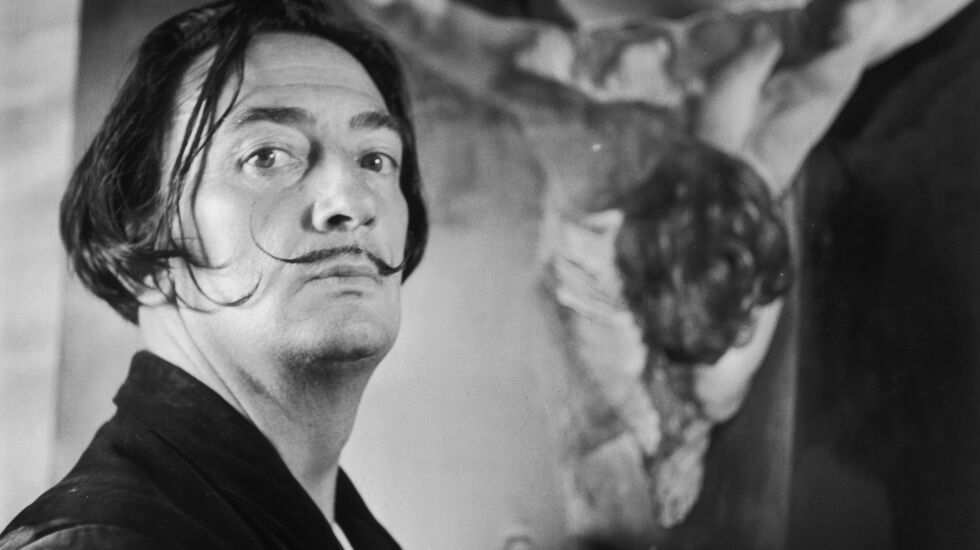

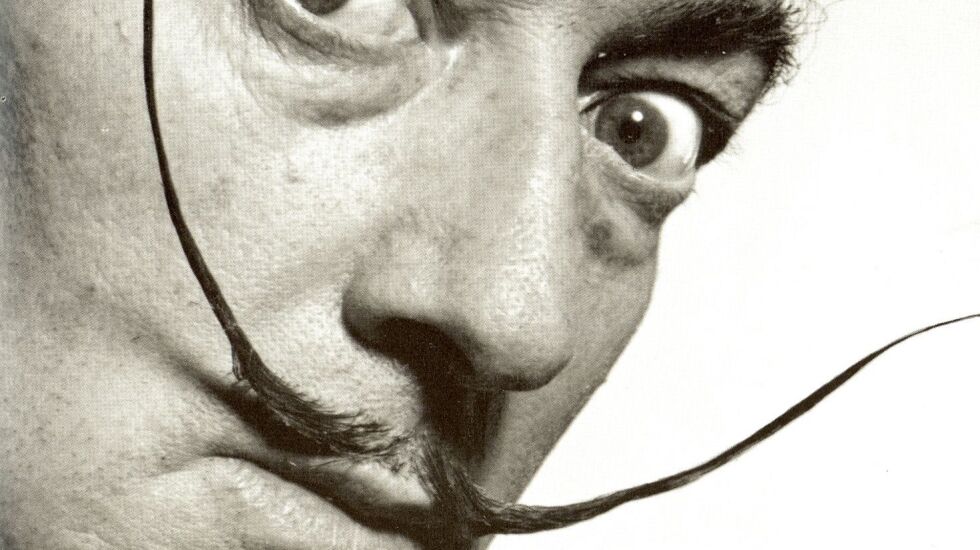

No 20th-century artist is more recognizable than Salvador Dali, with his trademark handle-bar mustache and wild-eyed looks.

But the surrealist’s over-the-top antics and voracious hunger for money and celebrity, especially later in his life, went far in damaging a serious artistic reputation that was crowned with a 1941-42 retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

“Many of my peers don’t look at Dali,” said Caitlin Haskell, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Art Institute of Chicago. “A lot of the academy, a lot of the curators of modern art think this is not as rigorous, not as meaty. Dali gets a bad name from people who typically like modern art.”

“Salvador Dali: The Image Disappears,” an exhibition that runs Feb. 18-June 12 at the Art Institute, seeks to repair his artistic standing and remind the art world and public why the Spaniard was one of the most important artists of his time. It is the museum’s first-ever such examination of the iconic surrealist.

“I am so excited about this show,” Haskell said. “I think it is going to knock people’s socks off, because people have stopped looking at the paintings. They think they know Dali, but they don’t.”

Unlike comprehensive examinations of Dali at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2005 and Paris’ Centre Pompidou in 2012-13, this is a focused, small-scale show that will take place in a 3,000-square-foot, second-floor gallery in the Art Institute’s Modern Wing.

It will contain 30 paintings, sculptures, drawings and collages and 20 books and related ephemera, including loans from museums from across North America and Europe. Although not a full-blown retrospective, it contains some of Dali’s most famous works like “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War),” a 1936 oil on canvas from the Philadelphia Museum.

“It sounds like we are patting ourselves on the back, but it’s a little jewel-box show,” said Haskell, who organized the offering with Jennifer Cohen. A member of the modern and contemporary department when work on the exhibition began, the latter now serves as the museum’s curator of provenance and research.

The Art Institute has displayed Dali’s work since two installments of the exhibition “A Century of Progress” in 1933 and ’34 in conjunction with the Chicago World’s Fair, and it has dozens of the artist’s creations across a range of mediums.

“Chicago as a city responds to surrealism very early on,” Haskell said, noting some that the city’s most prominent collectors began acquiring examples contemporaneously with the movement, especially those by Dali, and continued through much of the 20th century. Examples in this show include works in the Art Institute’s collection donated by Lindy and Edwin Bergman and Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Shapiro.

Indeed, it was the size and quality of the Art Institute’s Dali holdings that spurred Haskell and Cohen to propose a Dali show along with the surprising fact that museum had never previously presented a show devoted to the surrealist.

A third motivating factor emerged during research for the show and the conservation of some of the featured paintings: several art-historical discoveries, especially a big breakthrough connected to a misdated, 81½-inch-tall oil on canvas formerly titled “Visions of Eternity.”

In scanning a historical Vogue magazine feature on Dali’s “Dream of Venus,” which Haskell described as “surrealist fun house,” Cohen realized the imagery and iconography in the painting related to a display at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens.

The attraction, with a 25-cent entry fee, featured an irregular façade in a style reminiscent of Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí, semi-clad models in aquatic costumes and reproductions of famous artworks like Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus.”

Haskell and Cohen determined that “Visions of Eternity” — now renamed “Untitled (Dream of Venus)” — was actually part of a larger mural Dali created for “Dream of Venus,” a creation that was later cut into five sections, with the other four parts in the collection of a Japanese museum. “It’s a huge discovery and we are presenting that for the first time,” Haskell said.

“Dream of Venus” is the focal point of the third section of the Art Institute exhibition, which focuses on the 1930s, when, as Haskell puts it, “Dali becomes Dali.” He goes from being a member of the surrealist circle in Europe headed by André Breton to becoming what the curators call a “surrealist movement of one.”

That evolution is chronicled in the first section of the show, and the second focuses on Dali’s “paranoiac-critical method,” in which he drew on the subconscious to create works like “Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach” (1938) that can be seen and interpreted in two or more ways.

The show’s title derives from certain images in Dali’s works that seem be disappearing, such as a barely visible lap dog in the lower right corner of the “Inventions of the Monsters” (1937), an oil on canvas about the onset of World War II.

The curators worked with the museum’s conservators, who used infrared photography and other techniques, to learn more about these little-understood apparitions. They were able, Cohen said, to answer a key question around “Inventions” — whether the faintness of the dog image was deliberate or something that had faded with time.

“This is very close to what it would have looked like in 1937, and the ghostliness is intentional,” Cohen said.

Although no larger exhibition of Dali is in the works at the moment, Haskell hints that it certainly could be possible down the road. What will happen for sure, she said, is a reunion of the five sections of the “Dream of Venus” mural. “We will find a way to do that,” she said.