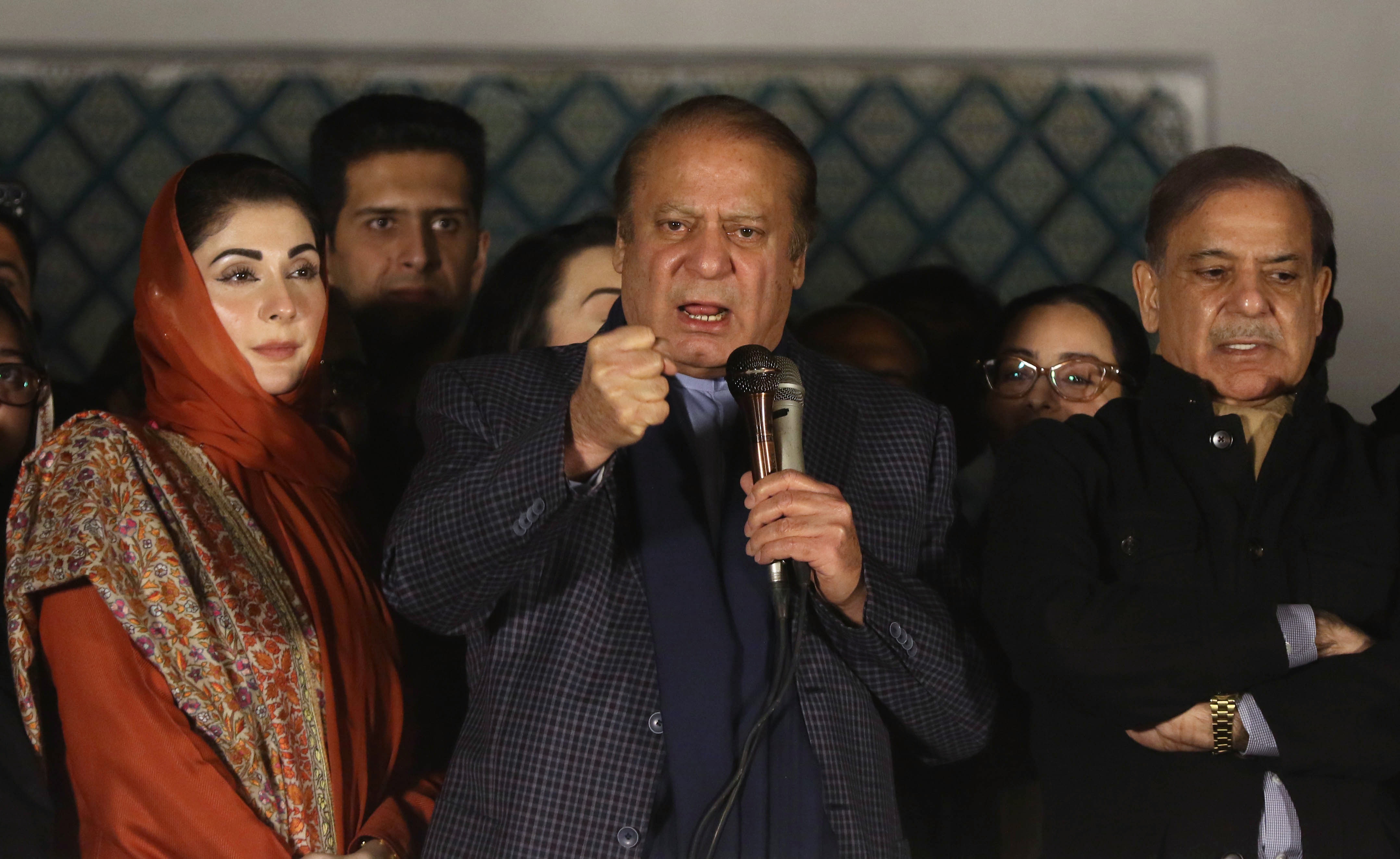

Islamabad, Pakistan — When Nawaz Sharif, the three-time former prime minister, emerged on the balcony of his party’s headquarters in Lahore on Friday night, fireworks went off as he was given a rousing welcome by the crowd of nearly 1,500 people.

Sharif started out with what has now become the staple of his public addresses, asking the crowd of his Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PMLN) supporters, “Do you love me?”. The response, “We love you!”, echoed among his adoring audience.

Yet, more than three days after Pakistan voted in general elections, there is little evidence that the sentiment of Sharif’s core supporters is shared by the wider public in the nation of 241 million people that stunned analysts in their voting patterns on February 8.

For weeks before the elections, the PMLN was viewed by experts as the favourite to secure a clear victory that would give the 74-year-old political veteran another chance to rule Pakistan. Once targeted by Pakistan’s military establishment, Sharif appeared to have won the favour of the generals for the 2024 vote.

So confident were Sharif and the PMLN of their win that they had scheduled a victory speech from their leader for Thursday night, barely hours after polls closed. Then, the results started coming in, and the bubble was burst.

“As the voting patterns emerged, it shocked and surprised the party, forcing a rethink which is why they were in complete silent mode for nearly 12 hours,” said Majid Nizami, a political analyst, and a specialist on elections.

When Sharif finally addressed supporters on Friday, he claimed victory, but acknowledged that his party had failed to secure a simple majority and so would need coalition partners to form a government.

“This was not the result the party was expecting. They thought they would achieve more than 85 percent of seats from Punjab province, but initial trends showed they were barely getting 50 percent of seats,” Lahore-based Nizami told Al Jazeera.

Almost all of the remaining seats in Punjab, the bastion of Sharif’s PMLN, went to candidates backed by former PM Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) — a party that experts believed had been decimated by targeted political and legal attacks in recent months.

What went wrong?

As the dust settles on the election results, the PMLN has emerged with 75 seats in the national assembly, trailing PTI-backed independent candidates by 20 seats.

The PTI alleges widespread manipulation and tampering, insisting that it has been denied a far larger majority and that their mandate has been “stolen” to benefit Sharif and his PMLN.

So, what happened to the PMLN, a party that, as late as early 2022, was leading opinion polls in popularity over PTI and was considered the strongest party in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous and electorally important province?

For Lahore-based political analyst and editor Badar Alam, the roots of PMLN’s disappointing performance in the polls can be traced back to April 2022 when Imran Khan, the PTI chief, and then-prime minister were ousted through a parliamentary vote of no-confidence.

At the time, Sharif was in self-imposed exile in the United Kingdom, after a series of corruption-related convictions. His party allied with the country’s other traditional political force, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and others under what was called the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM), to topple Khan’s government.

They succeeded. But, said Alam, “once Shehbaz Sharif, Nawaz’s younger brother, took over as prime minister, his attention went towards removing all the cases and convictions against his elder brother.”

These are cases that have haunted the Sharif brothers for three decades. The elder Sharif, who ruled the country twice in the 1990s, has been dogged by corruption allegations since then. In 1999, he was ousted in a military coup. His third term in power, after the PMLN won the 2013 elections, was marked by intensifying rivalry with Khan, who eventually won the 2018 election, backed at the time by Pakistan’s powerful military establishment that has ruled the country directly for more than three decades and has influenced politics from behind the scenes for much of the rest of the country’s existence.

Yet, since relations between Khan and the military soured, and he was ousted in 2022 — with the military now seemingly backing the PDM government — Pakistan has been through torrid political, economic and security crises.

Salman Ghani, a political analyst who has been covering the PMLN for a long time, said that as the leading party of the PDM, the decisions of that government hung heavy around the Sharif brothers’ necks.

“The 16-month rule of PDM caused almost irreversible damage to the PMLN. The tenure saw massive inflation, hitting the public everywhere, including their own vote bank,” Ghani told Al Jazeera. “Theirs is a party of development and the economy; people support them for delivery, not for ideology. That perception was destroyed in that time.”

Pakistan was on the verge of defaulting on loans last year, with its foreign reserves depleting to less than $4 billion dollars, and its rupee depreciating rapidly against the US dollar. A $3 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund helped stave off a default temporarily.

Sharif returned home from his exile three months before the elections. Many analysts believe that Sharif’s return and the subsequent change in his legal fortunes — with convictions against him dropped and restrictions against contesting elections removed — were made possible only because the military had decided to back him in the 2024 vote.

Meanwhile, Khan has been charged in more than 100 cases; was jailed in August and barred from contesting in the elections; and was sentenced in three separate cases just the week before the February 8 polls.

His party faced a crackdown — senior party officials were arrested, many were apparently coerced to leave his movement, and the PTI was barred from even using its election symbol, the cricket bat, in the elections. Its candidates were forced to contest as independents.

But the PTI wasn’t the only party that suffered. The PMLN and the military, seen by many ordinary Pakistanis as being behind the crackdown, made the mistake of underestimate popular support for Khan, said Ghani.

“When a person is oppressed, their support increases massively. We saw that in the case of Nawaz Sharif himself. Those who are pushed against the wall, they are the ones to retaliate the most. PMLN did not understand this,” he added.

Alam, the Lahore-based analyst agreed.

“Not even once did they [the PMLN] condemn the violence and persecution of the PTI; in fact, they played their part in fully subjugating them. This made PMLN a victimiser, resulting in public anger against them,” he said.

A party leader acknowledged that the PMLN had been blindsided by the recent election results.

“PMLN is on the defensive; Nawaz Sharif is on the defensive,” he told Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

The insider also blamed “sycophants” within the party, whom he accused on focusing on their own interests, for the PMLN’s failure to adapt its messaging as public opinion started to swing against it.

“Nawaz Sharif used to be very adept at handling media himself, but now that isn’t the case,” he said.

While the PMLN supremo, in his speech on Friday, did name other parties the PMLN might seek alliances with to form a government, he did not mention the PTI.

Alam said that PMLN and Nawaz Sharif must show some “grace”.

“PMLN came in as a party that was a government-in-waiting. PTI and Khan were in survival mode, but they upset the predictions. The country is in crisis, and it is imperative for Sharif, if he thinks he is a statesman, to concede and ask PTI to form a government,” Alam said.

Lahore-based Ghani said that the election risked compounding the country’s political, economic, and security challenges.

“Countries, when they hold elections, their objective is to bring stability. Democracy functions when it holds elections, and a mandate is earned. In our country, the election result is causing further instability,” he added.

Ghani said that Sharif, in his Friday speech, ought to have acknowledged the support of voters for Khan and the PTI, and indicated a willingness to “reach out to them”.

But what about the party’s own support base and future? It’s not looking very good for the PMLN, said Nizami, the analyst.

“Their strength and hegemony were in central Punjab area, from where they used to sweep the number of seats. It was unthinkable for them to lose votes. Yet, they have been losing ground to PTI and are unable to stop the rot,” he said.

“They have much to ponder now.”