In mid-2020, amid a burgeoning pandemic, 19-year-old Llyr George – the younger brother of Love Island star Dr Alex George – died by suicide. What made it even more crushing for Llyr’s family, like countless others, was that there had been no warning sign. Unanswered questions only compounded the grief. “Sadly, men are still much more likely to take their own life than women,” his brother says today – three-quarters of UK suicides in 2020 were by men. “The awful shame is [that many] don’t tell you, so you’re not aware that they’re struggling. We know that men generally use violent forms of suicide, while women have more help-seeking behaviours and will often present to A&E or they’ll talk to their friends.”

Since his brother’s passing in July 2020, the man affectionately known as Dr Alex has used his platform to help ensure other individuals don’t suffer in silence. Appointed Downing Street’s Youth Mental Health Ambassador last year, he’s under no illusions as to the task at hand. “Fundamentally we have a treatment-based model in this country where mental health services are expected to deal with everyone’s struggles. They’re actually designed for only about three per cent of everyone they see – for anorexia, bipolar disorder or other psychotic illnesses. Whereas so much of anxiety and depression – even early body image problems – can be dealt with in the community.”

Consequently, George is calling on Liz Truss to fund 190 Early Support Hubs. Designed to be walk-in and with no wait time – and target people up to the age of 25 – they should, so goes the thinking, quash early anxiety before it spirals into something far worse. Case in point: “One of the biggest mistakes we’ve made when talking about body image is that we mostly talk about women,” he says. “But hundreds of thousands of young men around the country are taking anabolic steroids to change the way they look. When I was aged 15, I wouldn’t see men with perfect bodies day-to-day unless I was buying Men’s Health magazine. Now you go onto Instagram and that’s all you see. Men are affected by it.”

The Love Island alumnus is reminded of his own battles with body image, including a short period prior to entering the villa. “Before the show, I felt a massive pressure to look a certain way; I was training two hours a day, starving myself, not seeing friends. I wouldn’t even have a coffee because I didn’t want the calories with milk in. Even if I looked at what stereotypically might be seen as a good shape, I felt absolutely horrendous.”

Of course, it’s not only young men who are being failed by society right now. In 2021, males aged between 50 and 54 were found to have the highest suicide rate in England and Wales. Kris Hall, founder of a non-profit tackling mental health issues in hospitality called The Burnt Chef Project, also suggests that traditionally male-dominated industries foster stress and anxiety. “Within hospitality, and certainly within the male arena of this, you’re under a lot of pressure and you’ve got to ensure you’re not the weak link,” he explains. “You don’t want to be the one to sink the ship, especially when everyone has high levels of stress.”

When it comes to professional kitchens, for example, the 35-year-old regularly informs chefs that there’s nothing unmasculine about being vulnerable. “Being able to identify that you are human and susceptible to emotions and feelings and illnesses is a powerful tool to be able to use within a 70 per cent male-dominated environment. You can still be stoic and lead with courage.”

Over the past decade, Hall’s scheme has supported and trained thousands of individuals across hundreds of countries. As part of its recent Workplace Stress Guide, surveying 673 people working across the hospitality sector (almost a sixth of whom were men), 69.44 per cent of male workers claimed that unrealistic time pressures had impacted their wellbeing. Ultimately, says Hall, we’ll only be able to create safe spaces for men to seek solace and open up if we focus on company-wide culture, and not solely a few bad eggs.

“Everyone views the stereotypical angry male chefs of the world as very aggressive, dominating characters,” he explains. “But I see people who’ve succumbed to high levels of stress over a period of time, whose ability to cope in an emotionally intelligent way has been severely impacted. Unless you provide people with the tools and support they need to understand, stop and swap that behaviour, then they’re not going to change.”

There are estimated to be over 1.5 million people currently waiting for a mental health appointment with the NHS. This isn’t any great surprise for Hall, who opted to seek private help after he himself reached crisis point in his twenties and found himself at the back of a telephone queue. One decade and a global pandemic later, he warns that – aided by one of the worst cost of living crises in modern history – we could be sleepwalking into a new nadir for men’s mental health. “Post-Covid, we’re already seeing millions of people on waiting lists to access therapy for at least three to six months,” he says. “At the same time, we’ve got private therapists increasing their costs due to the supply and demand equilibrium.”

Much like George, Hall believes it’s unfair to blame the NHS. It’s simply too big for that. “As awareness of mental health grows, people are asking for help sooner, but we don’t have the mechanisms to cope. That’s why I feel so passionate about creating free-to-access services to help stem the tide.”

Another individual bringing these topics out of the shadows right now is Conor O’Keeffe, an ultrarunner from Cork who recently ran the equivalent of 32 marathons in 32 days across 32 Irish counties. The endurance athlete even started the challenge with 32 pounds on his back to symbolise negative thoughts. He shed a single pound per day to help raise over £60,000 for Pieta House, just one of the charities currently bearing some of the load for Ireland’s similarly creaking mental health services.

Along the way, O’Keeffe, 30, was joined in person by followers on social media and listeners of his podcast. One encounter with a young man in County Clare sticks in the mind. “It was surface-level chat – college, sport, future plans,” O’Keeffe remembers. “Once we’d had a little run together he jumped in his car and drove off.” Minutes later, however, the teenager pulled up in front of O’Keeffe and hopped out of his car with a different demeanour. “I could see tears in his eyes and he just put his arms out for a hug, telling me that my podcast helped him so much. Now, he’s the typical guy you would read about in the newspaper taking his own life – outgoing, fit, healthy, handsome, a genuine guy you wouldn’t imagine had a care in the world. Obviously, he just felt nobody understood him.”

Clearly, O’Keeffe did. But how do we create more of these conversations? “What I’ve found men respond especially well to is ‘no bull***’,” O’Keeffe says. “They want honesty. What they don’t need is a campaign by companies jumping on the bandwagon because it’s the hot thing to make money out of. We need real guys who’ve been affected, talking about real experiences, warts and all. Rather than saying ‘I felt really bad’, we need to be candid, ‘Yeah, I felt like throwing myself off a bridge and not waking up again’.”

He speaks from experience. Before finding his purpose through running, O’Keeffe would drive around his hometown with a sense of numbness, feeling “listless, lacklustre, depressed, and sluggish” to the point he wanted to smash his car into a wall. “I’m incredibly grateful that whatever was inside kept me going”.

O’Keeffe also believes that one less talked-about reason for rising male suicide is the uncertainty of the modern world. “The idea of what a man is has been changing over the last number of years,” he says. “Our grandfathers knew what their place was within the family unit and therefore within society itself. There isn’t this jigsaw [that] we can fit into seamlessly anymore. The landscape had to change of course – women putting their careers first and having kids later – but we’re still figuring things out. For men, confidence and self-esteem are being chipped at by modern life. That is something that we struggle with. As a gender we are also conditioned from childhood to ‘man up and get on with it’ – so the earlier we can start talking to kids about [their] emotions the better. It’s tough to get through to a five-year-old year on a deep level, but it’s not impossible. It starts from there.”

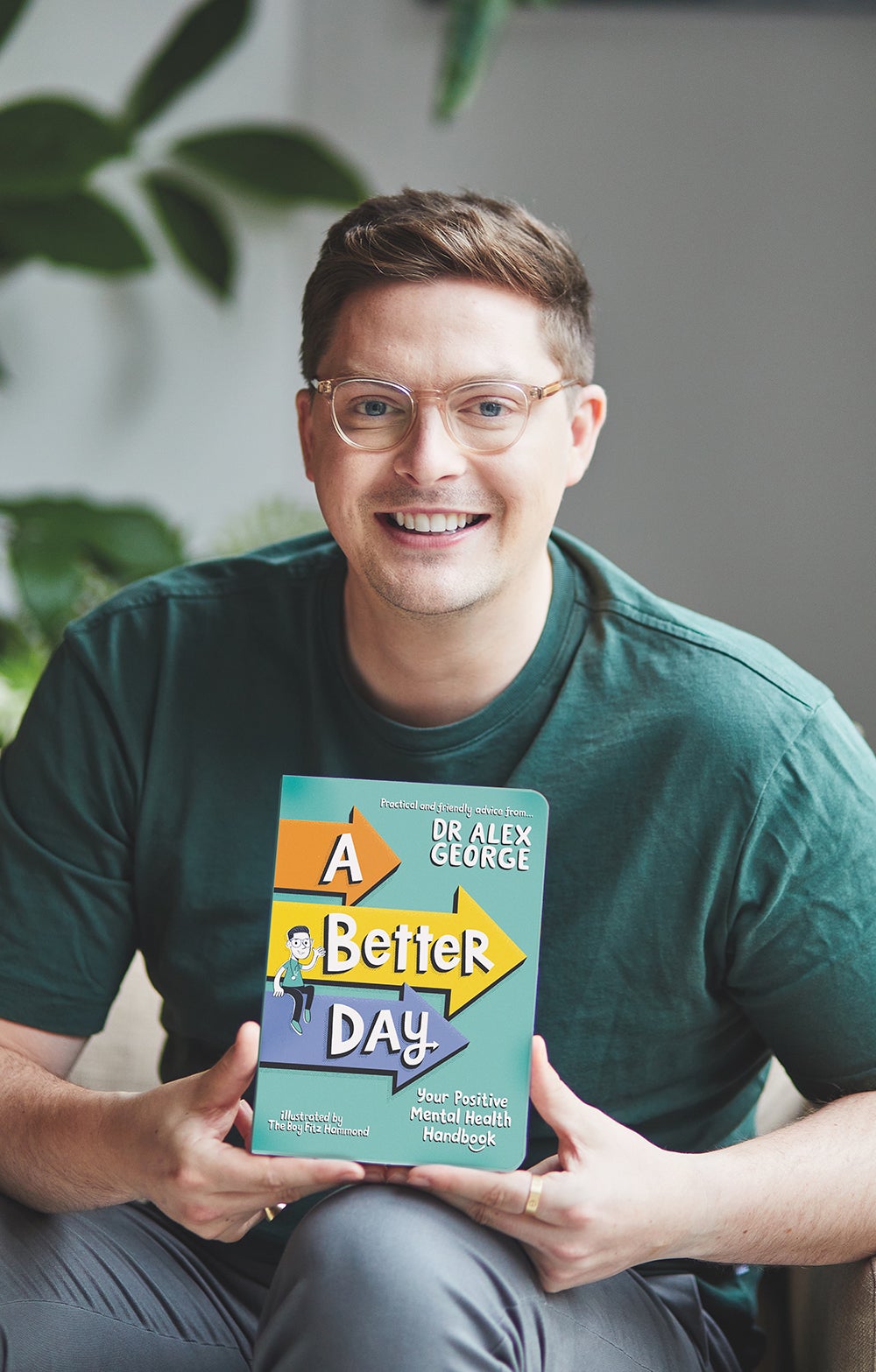

It’s also one of the reasons George has just published a children’s book about mental health – A Better Day: Your Positive Mental Health Handbook – and aimed at readers aged nine and up. “Picture Wembley Stadium full of children and multiply that by six,” he says. “That’s roughly the number of children currently waiting to be seen by mental health services in the UK. The problem is rising and getting worse. I’ve had loads of unbelievable messages from parents and kids already. Writing this book is to help prevent things like what happened with my brother. I want people to live and thrive instead of simply surviving life. It doesn’t have to be that way.”

‘A Better Day: Your Positive Mental Health Handbook’ by Dr Alex George, published by Wren & Rook, is available in all good bookshops now.

If you are experiencing feelings of distress, or are struggling to cope, you can speak to the Samaritans, in confidence, on 116 123 (UK and ROI), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website to find details of your nearest branch.

If you are based in the USA, and you or someone you know needs mental health assistance right now, call the National Suicide Prevention Helpline on 1-800-273-TALK (8255). This is a free, confidential crisis hotline that is available to everyone 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

If you are in another country, you can go to www.befrienders.org to find a helpline near you.