For anyone trying to understand where interest rates and inflation are heading, it has been a strenuous few days. Jay Powell, chairman of US central bank the Federal Reserve, warned senators he may have to do more to fight inflation than expected, indicating the prospect of interest rates rising more sharply again. Similarly Christine Lagarde, his counterpart at the European Central Bank (ECB), has said that the eurozone is far from ready to declare victory over inflation.

But just as borrowing costs look set for uncomfortable new highs, there were signs of further complications in the form of a nasty sell-off of US banking stocks amid fears that rising interest rates are damaging their balance sheets. This then dragged down markets in Europe and Asia.

So where are we likely to be heading from here?

The core inflation problem

The world’s major economies have been fighting steep inflation for nearly two years now. After many years of prices only rising very slowly, annual inflation shot into double digits in many economies in 2022. This was thanks to supply chain disruptions in response to COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, which drove up energy and food prices.

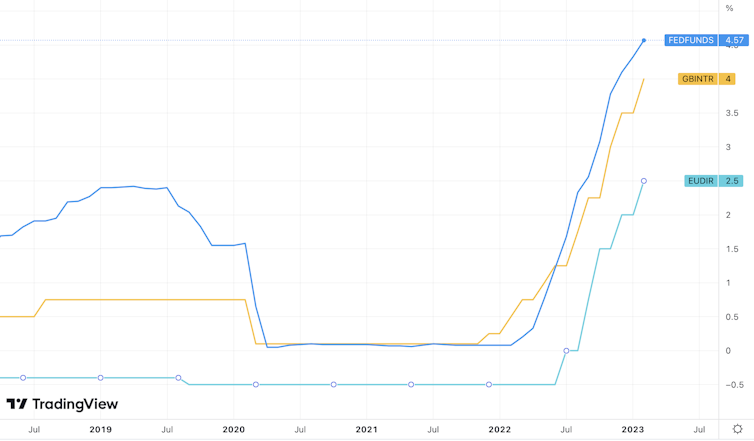

The ECB, Fed, Bank of England (BoE) and other central banks raised interest rates aggressively to try and bring inflation back within their 2% targets. The UK and US have raised their benchmark rates from near zero a year ago to 4% and 4.5% respectively, while the equivalent ECB rate is up to 2.5%. This has had a marked effect on banks’ lending rates, as anyone trying to borrow money in recent months will be well aware.

UK, US and Eurozone interest rates

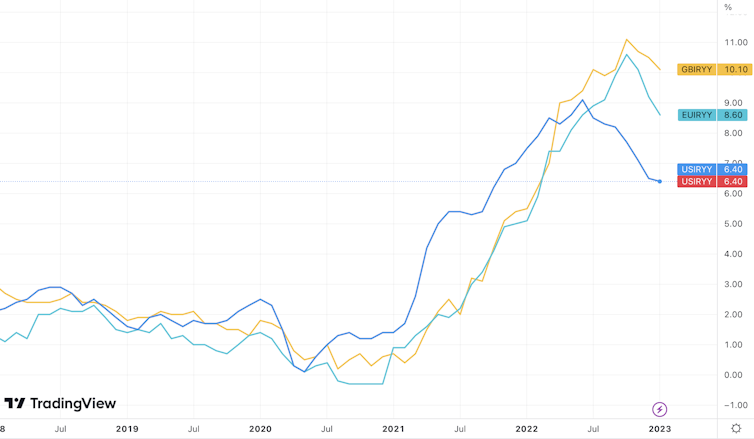

Until recently, it seemed likely that these rate rises were topping out because inflation had peaked. Headline inflation in the US fell from 9.1% in June to 6.4% by January partly thanks to easing food price pressures. This prompted the Fed to raise its benchmark interest rate by only 0.25 points in February, having been raising it in increments of 0.75 points only a couple of months earlier.

In the eurozone and UK, inflation has been moving in the same direction, with decelerating energy prices particularly benefiting Europe, though it has still been judged high enough in both areas to warrant monthly rises of 0.5 points. Overall, however, it suggested that central banks were on target to get back to 2% in the coming year or so.

Inflation rates in US, UK and eurozone

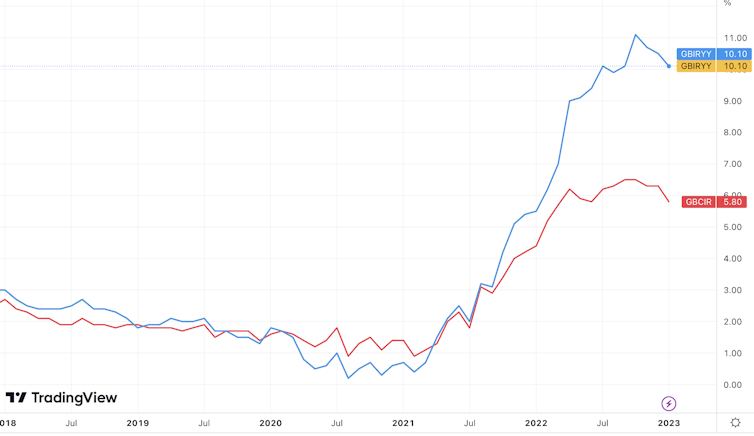

Yet it may have been too soon to breathe a sigh of relief. While the most recent monthly inflation numbers were still ticking downwards, it turned out to be a different story with core inflation. This closely watched measure strips out volatile items such as food and energy to give a clearer sense of price behaviour across the economy.

In the eurozone core inflation rose from 5.3% in January to 5.6% in February, while in the US it went from 4.6% in December to 4.7% in January. Both of the most recent numbers were above what the markets had been expecting. Only the UK’s most recent core inflation has been below expectations, though at 5.8% it’s still much higher than the Bank of England would like.

UK inflation vs core inflation

The reason why core inflation is staying raised could be linked to the fact that unemployment is so low. In the eurozone’s services sector, for example, we’ve been seeing rising wages as companies compete to pay for workers. Another factor has been companies raising their prices more quickly than usual to maintain their profit margins.

What it means

As most consumers will know only too well by now, raised inflation erodes your living standards. It means that people can buy fewer items with the same amount of money, making weekly shopping increasingly stressful.

As Powell and Lagarde have been signalling, the latest inflation data point to a need for further aggressive interest rate rises to come. The ECB is due to make its next decision on rates on March 16, with the Fed and BoE meeting the week after. Lagarde has already said it is “very, very likely” that the eurozone’s rate will rise by another 0.5 percentage points, while the market expects a similar rise from the US.

The effects are simple: the higher interest rates, the more borrowers need to pay back. Mortgage holders with tracker mortgages or whose fixed deals are coming to an end will be paying more. There is the consolation that people will be paid more on their savings accounts, though there can be a lag.

The most recent data is the latest US jobs figures (known as non-farm payrolls), which point to a slight decline in the unemployment rate from 3.5% in December to 3.4% in January. This would normally be good news but lower unemployment and increases in monthly salaries are providing the cushion for consumers to spend more in response to rising prices, which is of course adding to the problem.

On the other hand, bank stocks are selling off because the markets worry that banks’ financial positions are being compromised by the effect of rising rates on their vast bondholdings: the higher the rates, the lower the value of bonds. This is potentially a concern, but at least for now it’s probably not going to change the direction of travel.

Until core inflation is definitely under control, borrowing costs are going to rise more sharply than everyone was hoping. All eyes will be on the US inflation data in the coming days to see if there is any reason to change course.

Supriya Kapoor ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.