The VR landscape is shifting and developers need to think more creatively about how games and experiences are created, as well as finesse the fundamentals of virtual reality, that’s what Seb Bouzac, creative director at Archaic tells me, as we sit down to chat about the state of VR.

The best VR headsets you can buy right now range in power and approach to delivering virtual reality experiences. From PSVR 2 to Meta Quest 3 and HTC Vive there’s a broad range of ways to engage, and each one brings with it challenges.

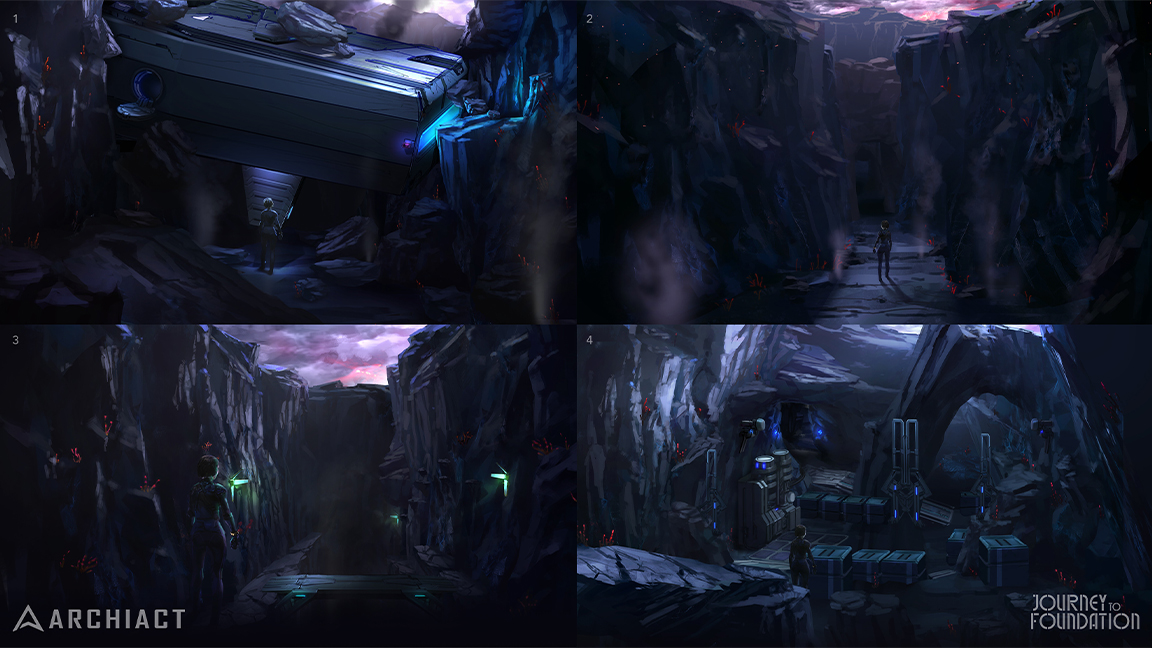

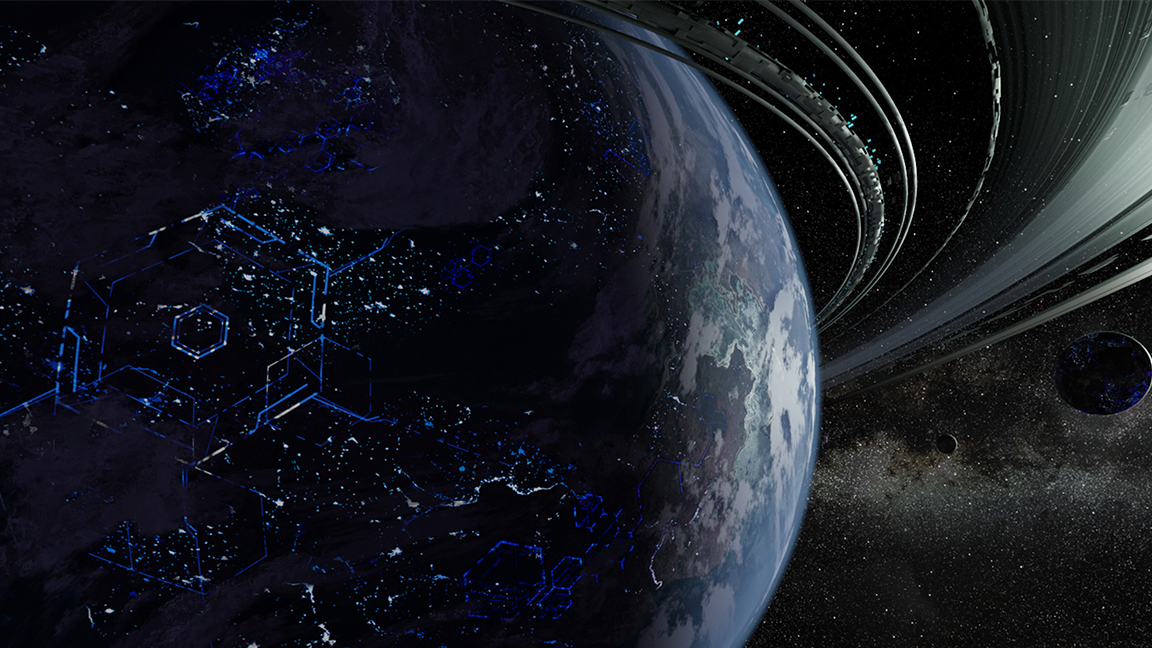

Archaic’s latest release is Journey to Foundation, a game based on the novels of Isaac Asimov and was considered as a connected experience to Apple TV’s epic Foundation series, and yes, an Apple Vision Pro version was muted. How the team approached its Foundation game is interesting, they pulled away from an Apple tie-in and instead created its own style, and I can some relief in Bouzac’s eyes as he tells me they were able to design their own look and style for Foundation, based on the constraints of aiming for the lower end Meta Quest 2 (it's compatible with Quest 3).

Journey to Foundation embraces the “hard sci-fi" aesthetic of the novels’ descriptions, grounded in the idea that technology has been present for so long that it just works, without anyone really knowing how. "We really tried to stay true to what we believed was the vision back then in the books,” says Bouzac, “creating a world that would be believable".

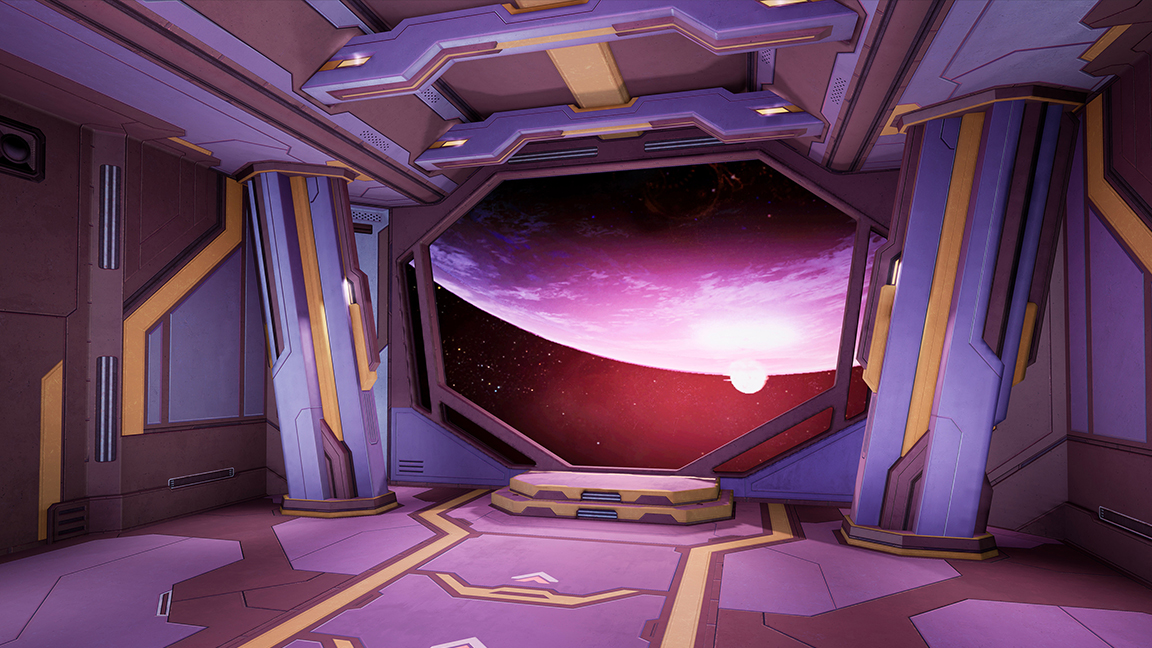

The game's art direction focuses on creating a world that feels both futuristic and aged, with a mix of interior stations, expansive space vistas, and abandoned architectural wonders. The challenge lies in balancing the visual aspirations with the technical constraints of VR hardware, especially when developing for platforms with varying capacities.

Why Apple Vision Pro matters

Bouzac is positive about Apple Vision Pro, saying, “having another player in the game is actually good because it's expanding the market in general, but it's also adding a new set of constraints for developers because now you have two spectrums to handle, the low lower end and the higher end. Unfortunately, you have to aim for the lower hand first because if you start with the higher res and have up to 30 people on screen and all these cool things then you try to drop to Quest and you realise ‘oh, I can only have five people on screen,’ so you need to completely change the design”.

With a slew of great VR games behind him, including Freediver: Triton Down and the VR edition of Doom 3, Bouzac and Archiact have a track record of getting the most out of the tech. He mentions how making Doom 3 had an impact on his approach to VR development and managing expectations of the tech being used.

"When we looked at the code and the game there was no way we could do everything we would have wanted to do if we had the mandate of, let's say, redesign Doom 3 from the ground up for VR. We would have changed everything," he reflects.

The experience of making Doom 3 VR taught Bouzac that the VR-ness of the medium matters above all, and for that game the team focused on changing the UI and how players interacted with the world over trying to rework the core gameplay. He also explains how making a game for the lower end of the VR spectrum and then upgrading visuals and features is a better method than going all-in on the best tech and working back; for Bouzac Meta Quest 2 is the base from which new games are created.

He riffs on this point and offers advice to any developer by emphasising the significant shifts in VR tech, especially with the introduction of affordable mobile headsets like Meta Quest 2 and 3, has changed the user base and expectations. However, he says, “For the developers it's getting more constraining because now you have to make sure the game works on, and is suited for, all kinds of platforms in general”. He adds, the upshot could likely lead to more platform exclusives, and we know Sony has that in the bank, just look at Horizon: Call of the Mountain.

Making sense of space in VR

So technology is shaping game design, and it’s not necessarily the leading edge innovation’s of PSVR 2, Quest 3 and Vision Pro, but instead the limitations of older headsets. This is the reality of game development, of managing budgets and making compromises. For VR, Bouzac explains, it comes down to convincing a space is real. He emphasises the importance of “creating spaces that feel relevant and believable, taking into account the player's natural expectations in a three-dimensional space […] Everything needs to be thought from that first-person view perspective”.

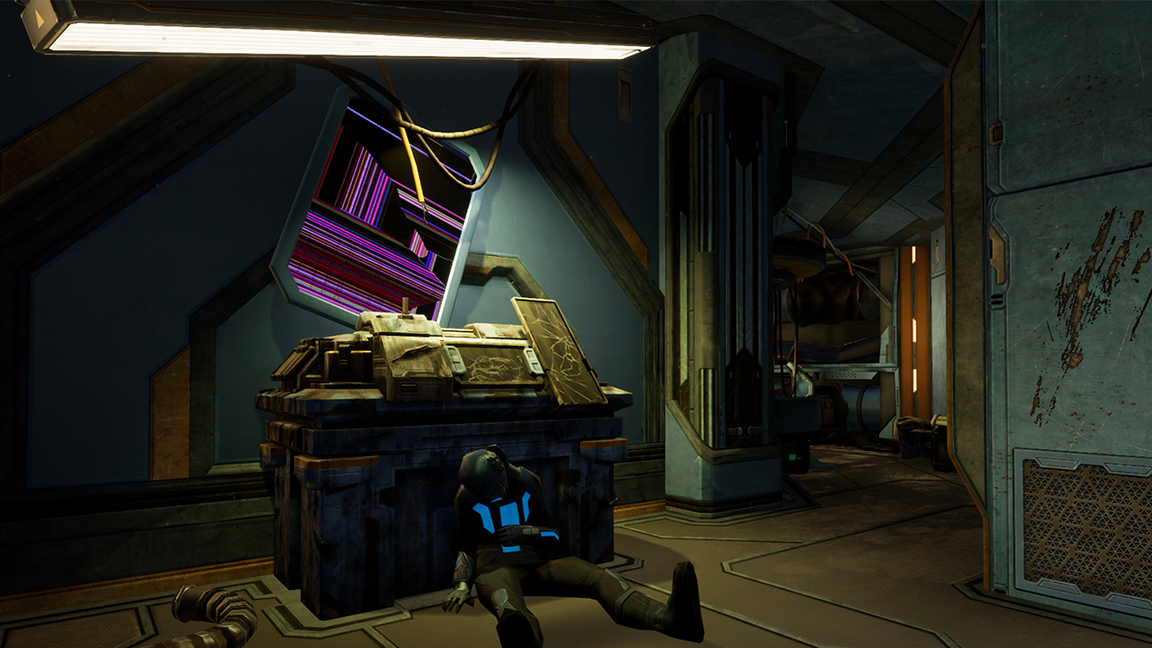

He explains how VR challenges traditional level design, requiring developers to think not only about the initial staging of a scene but also how it unfolds as players explore. The balance between indoor and outdoor environments, large-scale and intimate spaces, adds to the complexity of designing for VR. Bouzac explains, “In VR, a space needs to make sense, it needs to feel relevant to an existing or fantasy space but it still needs to give the player the right proportion, the right distance, the right staging, same when you enter a room [in real life]”.

Designing spaces for VR leads Bouzac to offer some advice to artists wanting to work in VR game development. For a start he explains how VR development is “10% creative and 90% problem solving”, which may sound harsh, but he adds, “you have to be creative to solve those problems”. He continues: “You spend more time figuring things out then applying the rules that you’ve learned in the past, so it's really a balance in understanding what you’re trying to achieve, and what's the best way to achieve it.”

VR art and development is not about set-dressing environments as you would in flatscreen games; in VR players expect to be able to interact with everything, “If I see something in VR I probably want to interact with it […] and if you don't plan on letting you interact with something it's better to not even show it, because otherwise you’re misleading or you are creating expectations that won't be fulfilled”.

The moment you create a world you want to be believable, it doesn't have to be realistic, it just has to be a believable world.

Seb Bouzac, Creative Director, Archaic

When it comes to concept artists’ portfolios there are some things he loves to see, and key to this is an understanding of space and immersion, and possibly more 3D artwork or a consideration of how space and player viewpoints are seen.

Bouzac explains: "The moment you create a world you want to be believable, it doesn't have to be realistic, it just has to be a believable world. Our concept artists, if they don't initially have that experience, will gain that experience by going through iteration. It's really about this idea of a 2D screen or 2D concept in VR. You almost need the other view, like your viewpoint right now [Bouzac gestures to me, looking at him], versus my viewpoint. You need to have two sides of the viewpoint because that's how it's going to really feel in the game versus a 2D experience.”

Start perfecting your hand animation

The same approach to VR environments plays out when it comes to how that world is interacted with, and this has meant hands and hand animation has become a new art form. What seems simple, is actually evolving into something very complex to get right, and can be a “combination of work between interaction design, animation, and sometimes engineering” teams, says Bouzac.

The simple act of grabbing a door handle and pulling up or down, requires planning and finesse. It needs to feel real and look obvious and natural in how, for example, door handles work. I’m learning from Bouzac that good VR design and animation is about observing the real world and breaking down how interactions work.

It’s about understanding “UX design in general, outside of gaming,” says Bouzac, revealing Archaic has animators “dedicated to just simply creating a player's hand, the hero hand, to understand the interaction” and this ensures ‘realism’ never breaks, “the moment that gets broken, that's where you start losing that immersion versus when you stop thinking that you are in a game”. He adds: “Definitely, hands and work and working around the hands is it's huge part of creating VR interactions in general.”

The focus on hands, and immersion, means animation in VR has a subtle shift in approach, as the usual cinematic sequences are jettisoned for in-world moments, and how hands are animated to develop character as much as realism. Bouzac laughs and tells me how the attention you’d usually put into a character’s animation is now focused on hands and it can become complicated because hands are intricate.

“So it becomes complicated,” he says, “but the good thing is, as an animator all it takes for you is to look at your hand grabbing something to understand what it is what I am trying to achieve. The easy part is that you can use your hands as a test ground to a test subject to see if it's actually looking good or not.”

Bringing characters to life

Just as developers need to create for the lower-end of headsets, Bouzac also reveals how upgrading to newer technologies can bring with it the opportunity to create new gameplay ideas and visual concepts. One such development has been Archaic's approach to facial animation in Journey to Foundation. The team has created an in-house tool that can generate facial expressions based on tagging specific words in the game’s script, using pre-made emotional responses.

Bouzac says, “which means that if you play the game, you'll see in some of the conversations, the character as they talk and lip sync, are actually animating their face in a way that matches that emotion that we set in the animation.”

Again, this is about the realistic constraints of game development and deciding where to place the most effort. Bouzac tells me the team could have put more focus into combat but for Journey to Foundation, a narrative-driven adventure, the focus was on character interaction. So the character interaction, the way we interact with characters, no matter the art style, whether realistic or stylised, what is important for us is that we feel that they appear believable”.

Journey to Foundation is available to buy now for Meta Quest 2, Meta Quest 3, Pico 4 and PSVR 2. Visit the the game's official website for more details.