In 1977, Associated Press reporter James W. Mangan's exclusive interview with a South Texas election judge who detailed certifying false votes for Lyndon B. Johnson nearly three decades earlier made headlines across the country.

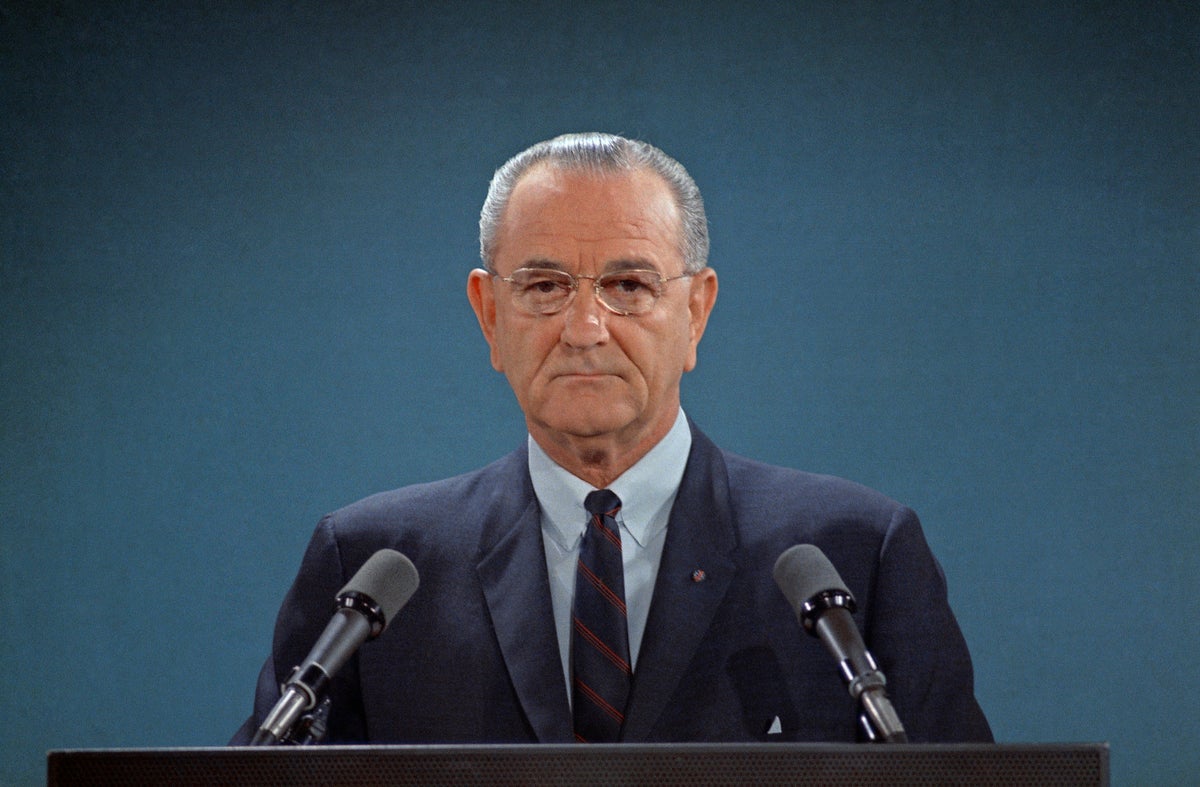

With the win by an 87-vote margin in the 1948 Democratic primary runoff, Johnson, then a congressman, easily defeated his Republican opponent to take a seat in the U.S. Senate, and he eventually ascended to the presidency.

Mangan spent three years pursuing the story, which pulled back the curtain on the victory that had drawn suspicions ever since election officials in rural Jim Wells County announced the discovery of uncounted votes in ballot box known as Box 13.

Headlines across the U.S. that accompanied the story included: “Polling Official: Phony Votes Stole ’48 Runoff for LBJ”; “LBJ’s election to Senate ‘stolen’”; “Texan Claims Fix in LBJ Election.”

Here's the story that ran July 31, 1977:

___

A former Texas voting official seeking “peace of mind” says he certified enough fictitious ballots to steal an election 29 years ago and launch Lyndon B. Johnson on a path that led to the presidency.

The statement comes from Luis Salas, who was the election judge for Jim Wells County's notorious Box 13, which produced just enough votes in the 1948 Texas Democratic primary runoff to give Johnson the nomination, then tantamount to election, to the U.S. Senate.

“Johnson did not win the election; It was stolen for him. And I know exactly how it was done,” said Salas, now a lean, white-haired 76; then a swarthy 210-pound political henchman with absolute say over vote counts in his Mexican-American, South Texas, precinct.

The controversy over that runoff election has been a subject of tantalizing conjecture for nearly three decades, ever since U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black abruptly halted an investigation, but the principals have been silent. George B. Parr, the South Texas political boss whom Salas served for a decade, shot himself to death in June 1975. Johnson is dead and so is his opponent. Salas, retired from his railroad telegrapher's job, is among the few living persons with direct knowledge of the election.

Johnson's widow, Lady Bird, was informed of Salas' statements and said through a spokeswoman that she “knows no more about the details of the 1948 election other than that charges were made at the time, carried through several courts and finally to a justice at the Supreme Court.”

The Associated Press interviewed Salas frequently during the past three years, seeking answers to questions that, save for rumors, were left unanswered. Only recently did Salas agree to tell his full version of what happened. In his soft Spanish accent, Salas said that he decided to break his silence in quest of “peace of mind and to reveal to the people the corruption of politics.”

Salas says now that he lied during an aborted investigation of the election in 1948, when he testified that the vote count was proper and above board. “I was just going along with my party," he says.

He told the AP that Parr ordered that 200-odd votes be added to Johnson's total from Box 13. Salas said he saw the fraudulent votes added in alphabetical order and then certified them as authentic on orders from Parr.

The final statewide count, including Box 13 votes, gave Johnson an 87-vote margin in a total tally approaching 1 million and earned him the tongue-in-cheek nickname: “Landslide Lyndon.”

Texas Democrats were split in 1948. Johnson, then 39, a congressman, represented “new” Democrats in his bid for the U.S. Senate. His primary opponent was Coke R. Stevenson — 60 years old, three times Texas governor, never beaten and the candidate of the “old” wing of the party. They called him “Calculating Coke.”

The vote in the July primary was Stevenson 477,077, Johnson 405,617. But a third candidate, George Petty, siphoned off enough votes to deny Stevenson a majority, forcing a runoff between Stevenson and Johnson, set for Aug. 28, 1948.

In the interim, Johnson intensified his campaign. One of the places he went stumping was the hot, flat, brush country of South Texas, George B. Parr country, where the Mexican-American vote seemed always to come, favoring Parr's candidate, in a bloc.

The power had passed to Parr from his father, Archie, a state senator who had sided with Mexican-Americans in a 1912 battle with Anglos over political control in Duval County. The younger Parr was known as the “Duke of Duval.”

Salas said he was Parr's right-hand man in Jim Wells County from 1940 to 1950, but quit over Parr's failure to support a fellow Mexican-American who had been charged with murder.

“We had the law to ourselves there,” Salas said. "It was a lawless son-of-a-bitch. We had iron control. If a man was opposed to us, we'd put him out of business. Parr was the godfather. He had life or death control.

“We could tell any election judge: ‘Give us 80 per cent of the vote, the other guy 20 per cent.’ We had it made in every election."

The night of the runoff, Jim Wells County's vote was wired to the Texas Election Bureau, the unofficial tabulating agency: Johnson 1,786, Stevenson 769.

Three days after the runoff, with Stevenson narrowly leading and the seesaw count nearly complete, Salas said, a meeting was called in Parr's office 10 miles from Alice. Salas said he met with George B. Parr; Lyndon Johnson; Ed Lloyd, a Jim Wells County Democratic Executive Committee member; and Bruce Ainsworth, an Alice city commissioner. Lloyd and Ainsworth like Johnson and Parr, now are dead.

Salas told the AP:

"Lyndon Johnson said: ‘If I can get 200 more votes, I’ve got it won.'

“Parr said to me in Spanish: ‘We need to win this election. I want you to add those 200 votes.’ I had already turned in my poll and tally sheets to Givens Parr, George's brother.

“I told Parr in Spanish: ‘I don’t give a damn if Johnson wins.'”

“Parr then said: ‘Well, for sure you’re going to certify what we do.”

“I told him I would, because I didn't want anybody to think I'm not backing up my party. I said I would be with the party to the end. After Parr I and I talked in Spanish, Parr told Johnson 200 votes would be added. When I left, Johnson knew we were going to take care of the situation.”

Salas said he saw two men add the names to the list of voters, about 9 o'clock at night, in the Adams Building in Alice. He said the two were just following orders and he would not identify them.

The AP interview then produced this exchange:

Q. When you told Parr you would certify the votes, he said he would get someone else to actually add the names?

A. Yeah. And I actually saw them do it. I was right there when they added the names.

Q. Were all 200 names in the same handwriting?

A. Oh, yeah. They all came from the poll taxes, I mean, from the poll tax sheet.

Q. But some were dead?

A. No one was dead. They just didn't vote.

Q. So you voted them?

A. They voted them.

Q. You certified?

A. I certified. So did the Democratic County chairman. I kept my word to be loyal to my party.

Q. Had some of those names already voted?

A. No, they didn't vote in that election. They added 'em. They made a mistake of doing it alphabetically.

Q. They added them alphabetically, as though they had walked in to vote alphabetically?

A. Yeah, that's what I told George B., and he wouldn't listen to me. I said: ‘Look at the A, you add 10 or 12 names on that letter. Why don’t you change it to the other, C or D or X, mix ‘em up?’ George said, ‘That’s all right.' George was stubborn. He would not listen to anybody. But it was stupid. They went to the poll tax list and got those names. For instance, on the A they got 10 or 12 names.

Q. People who had not voted?

A. That's right. they went on the B the same way, until they complete 200, and I told George, ‘That’s wrong.'

Q. While they were doing it you told him?

A. Yeah, and he said: ‘It’s OK.'

Q. They should have changed the handwriting?

A. How? Only two guys? How they going to change it? The lawyers spotted it right away, they sure did.

Six days after the runoff, with Stevenson still holding a narrow lead in the statewide count, a second telegram was sent, changing Jim Wells County's vote to: Johnson 1,988, Stevenson, 770.

Johnson gained 202 votes; Stevenson 1. They came from Box 13.

The next day, the official statewide vote canvass gave Johnson 494,191 and Stevenson 494,104.

Stevenson protested. Johnson said that if Stevenson had evidence, it was his duty to go to a grand jury. “I know that I did not buy anybody's vote,” Johnson said.

Stevenson went to federal court in Fort Worth and, on Sept. 14, Judge T. Whitfield Davidson signed a temporary restraining order forbidding certification of Johnson as the Democratic nominee. The judge ordered an on-the-spot probe of voting in Jim Wells County.

When that inquiry began, on Sept. 27, reporters from around the country showed up in Alice. By then it was national news.

The same day, in Washington, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Black agreed to hear Johnson's petition to lift the injection. Johnson's attorney was Abe Fortas, in later years a Johnson appointee to the high court.

Stevenson was in Alice that day; Johnson was on President Harry S. Truman's campaign train. During a campaign stop in Temple, Tex., Truman brought Johnson to his side and publicly endorsed him as the next senator from Texas. Also on the train at San Antonio that day, according to Salas, were Parr, who had received a presidential pardon from Truman in 1946 after serving nine months on an income tax conviction, and Lloyd, the Jim Wells County executive committeeman.

Salas told the AP he was summoned the next day by Lloyd and told: “Luis, everything is all right. We talked to Truman on the train. Don't worry about the investigation.”

Two days later, Justice Black, in an order he dated himself in longhand, voided the temporary injunction against putting Johnson's name on the ballot and ended the investigation. Black said, “It would be a serious break with the past” for a federal court to determine an election contest.

Stevenson had lost; Johnson had won.

That ended Stevenson's political career. He retired to his Hill Country ranch, insisting until he died in 1975 that the election had been stolen from him. Johnson became a power in Congress, and 15 years later he was president.