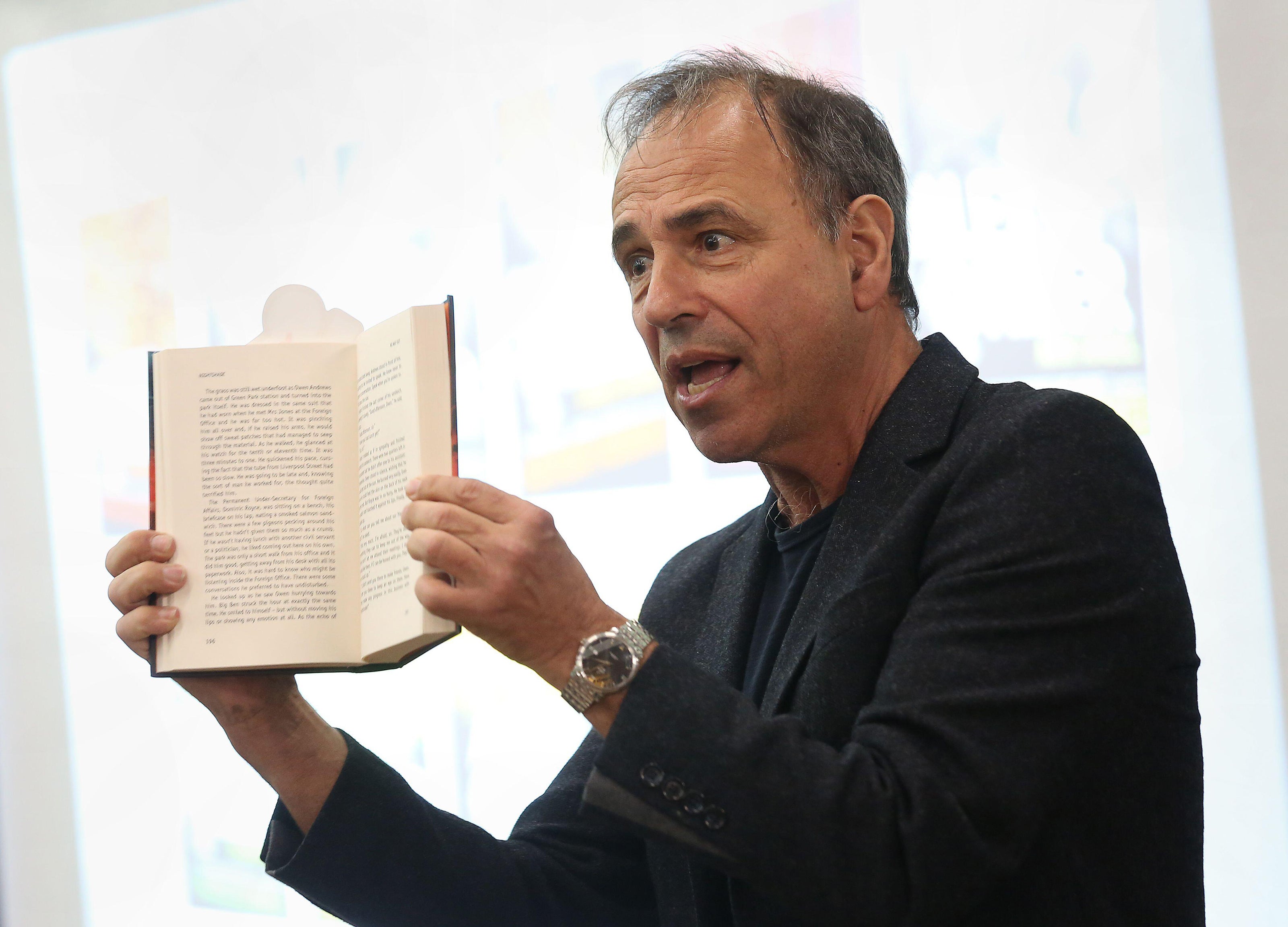

There’s a restlessness to Anthony Horowitz, master of the mystery novel, TV writer, playwright and journalist, a whirlwind of ideas, juggling so many creative balls at once that it’s amazing he has such clarity of thought.

To describe the bestselling author as prolific is an understatement. Author of some 56 books including the Alex Rider teen spy series, three James Bond novels and several reimaginings of Sherlock Holmes, plus TV hits including Midsomer Murders, Foyle’s War and Poirot, he’s already had three books published this year – he was on a roll during the pandemic – and is now looking forward to making a six-part TV series with his producer wife Jill Green.

Mementoes related to Horowitz’s work adorn his office – a human skull on his desk reminds him time is short, Tintin figurines because Tintin was his first inspiration, models from the world of Bond, favourite Sherlock Holmes books, a computer from the Stormbreaker movie.

“I try to make sure that wherever my eye settles in my office, it is something that will remind me of my work,” he observes.

Horowitz, 67, divides his time between his London home and his Suffolk bolthole, switching off to walk his dog for at least two or three hours a day. He runs all his work past Jill, to whom he has been married for 34 years and with whom he has two grown-up sons.

“Jill reads everything I do first and is my best and wisest critic and is completely honest. It matters a great deal to me what she thinks. We’ve always had a marriage and a relationship partly based on work because we are both very driven.”

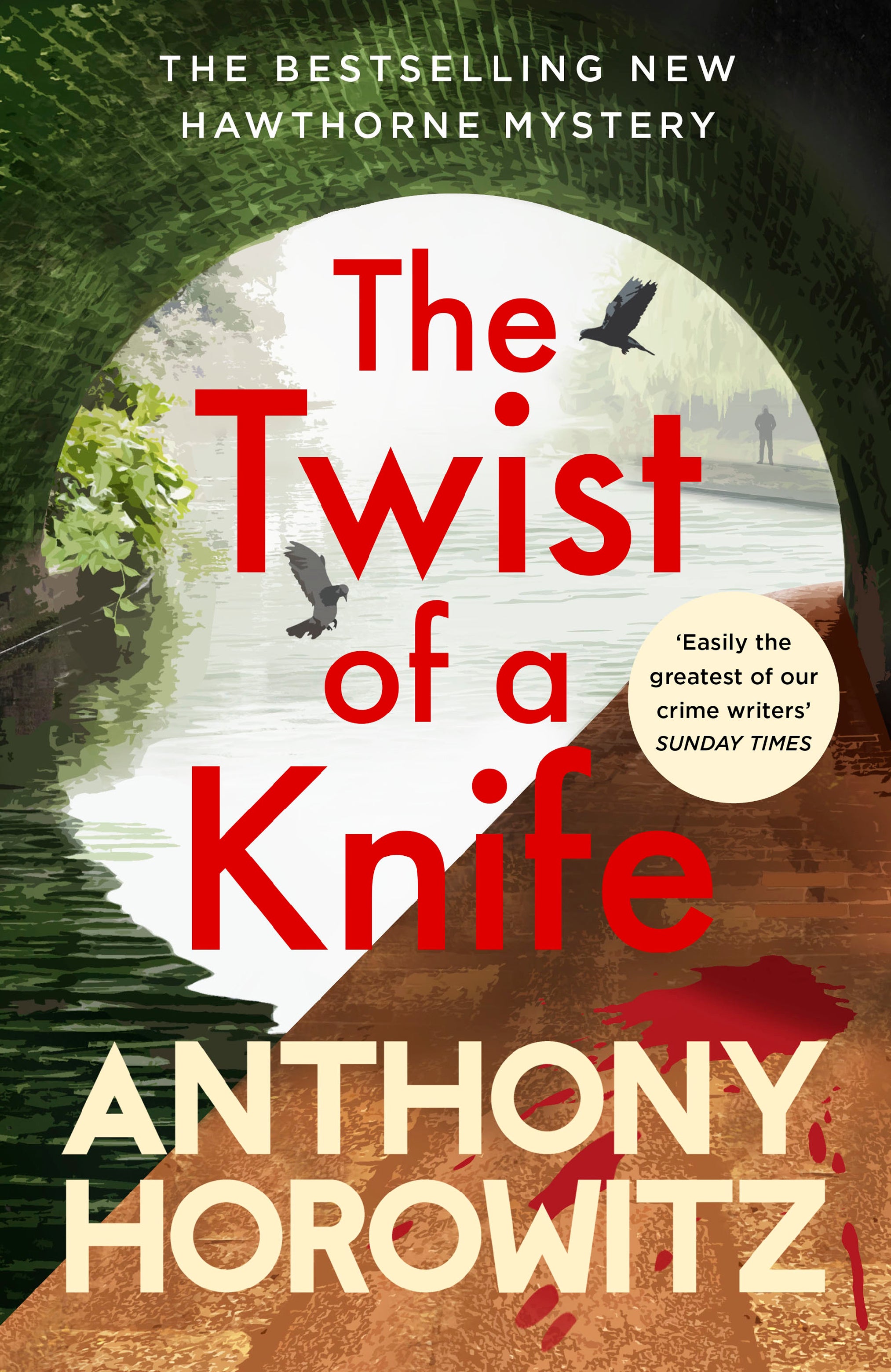

Today, while in the process of moving to West London, he’s squeezed in our interview to talk about his 56th book, The Twist Of A Knife, a clever locked room mystery and fourth in the Hawthorne and Horowitz series.

Horowitz appears in the book as himself, accused of murdering a theatre critic who gives his new play, Mindgames (which was actually a play that he wrote), a bad review. But the inspiration, he says, didn’t come from his notices for Mindgames.

“It was Dinner With Saddam, my last play, which I always say divided the critics – it was 50:50. Half of them hated it and half of them loathed it,” he quips.

Jokes aside – and there are plenty of lighter moments in the latest novel – in recent weeks Horowitz has voiced his concern at how the so-called ‘cancel culture’ is putting writers in fear of what they are penning. He thinks carefully before elaborating today.

“These days, writers do have to self-censor. Before you speak in an interview, or at a literary festival when you are answering questions, and when you are writing a book, you always have to put a three-second delay into your mind so that what comes out of your mouth or on to the page has that consideration.

“We are living in a society where people seem to take offence a great deal more easily than they used to, where the reaction is often a little extreme. This is a result of social media, which is not a great platform for reviewing or criticising because it’s so black or white, yes or no, good or bad.

“There’s no grey area on social media, which has fuelled the society in which people are less willing to consider the nuances of an argument and go immediately for one point of view or another, a digital binary choice, or, which is worse, begin to have jaundiced views of the person whose view they are arguing with.”

Horowitz has personal experience of this, saying: “I noticed on Twitter that if people send me angry or unpleasant tweets, they don’t know who I am. They have no idea what I really think. They have an idea in their head which is far from the truth.”

And the results be dangerous, he contends: “Social media is fuelling a view of society which is often harmful at best and can be dangerous and violent.

“One is seeing quite unpleasant and vituperative arguments on social media at the moment, and we are living in the shadow of what happened to Sir Salman Rushdie, which to me is tenuously connected.

“I’m not saying that this anger on social media led to that awful event. One has to think about the freedom of speech issues, religious intolerance issues and other issues, but nonetheless my guess is that the person who attacked Sir Salman had not read his book (The Satanic Verses) and this overwhelming feeling of anger and violence is leading us into dark places.”

In an interview with the New York Post the man who allegedly stabbed Sir Salman on stage at an event in New York on 12 August was reported as saying he had read two pages of The Satanic Verses. Hadi Matar, 24, has pleaded not guilty to attempted murder and assault charges.

Making his argument more widely, Horowitz continues: “I do think writers are by and large now afraid of causing offence.

“They have to pause for thought in everything they do. The extremes of it is when you get people like Sebastian Faulks saying that he might even consider not writing a description of a woman in his books. What an earth is going on if that is the case?”

Horowitz’s children’s books, he says, are edited with some caution.

“My publishers have been more nervous in the editing of my books. Issues of levels of violence, language and attitudes do get more closely examined. I’ve had some of my books read for sensitivity. But that’s the 21st century. People’s attitudes have changed and what didn’t offend people 40 years ago does now.”

He’s heartened that the books he wrote 35 years ago are still in print, so feels that had there been any offensive content in them, somebody would have told him.

“There are very few things I regret – maybe odd things like making fun of vegetarians, which I did 30-something years ago. Now I barely eat meat myself. Your attitudes do change, but because I’ve always focused on entertaining people rather than trying to upset them, there’s nothing in my books I regret.”

What about James Bond, who might well be seen as un-PC in this day and age?

“When I’m writing the books I always hear Sean Connery and see Daniel Craig. I am perfectly happy to defend Bond. My Bond is a man of the 50s and 60s, so he lives by a different moral code to the one we have now.

“I refute the suggestion that he is chauvinistic or sexist or misogynistic. I think he treats women very well in the books and has great respect for them, yet I admit he has some of the attitudes that we now would not celebrate in the 21st century, but that’s because the books were written in the 20th century. It was a different time.”

Horowitz emphasises that the type of contemporary murder mystery he writes focuses on intellectual ability rather than digital discoveries.

“I’m not interested in forensics or computers or police analysis – I’m interested in a more intellectual and entertaining form of crime, which harks back to Conan Doyle and Agatha Christie. I like the pace of it.

“If you don’t have mobile phones, information isn’t instantly at your fingertips. I like detectives to have to sit down and think, rather than pressing a couple of computer buttons to find the answer. It makes for a more entertaining read.”

Never still for long, he and Jill are working on six-part TV series and hope to create a TV adaptation of his novel Moonflower Murders next year. There’s no sign of him slowing down, although he keeps threatening to do less but then gets a stream of ideas and finds it hard to say no to himself.

Future ambitions? “Write a better book – the next one’s got to be better.”

The Twist Of A Knife by Anthony Horowitz is published by Century, priced £20. Available now