Greater conservation efforts are needed to protect Antarctic ecosystems, and the populations of up to 97% of land-based Antarctic species could decline by 2100 if we don’t change tack, our new research has found.

The study, published today, also found just US$23 million per year would be enough to implement ten key strategies to reduce threats to Antarctica’s biodiversity.

This relatively small sum would benefit up to 84% of terrestrial bird, mammal, and plant groups.

We identified climate change as the biggest threat to Antarctica’s unique plant and animal species. Limiting global warming is the most effective way to secure their future.

Threats to Antarctic biodiversity

Antarctica’s land-based species have adapted to survive the coldest, windiest, highest, driest continent on Earth.

The species includes two flowering plants, hardy moss and lichens, numerous microbes, tough invertebrates and hundreds of thousands of breeding seabirds, including the emperor and Adélie penguins.

Antarctica also provides priceless services to the planet and humankind. It helps regulate the global climate by driving atmospheric circulation and ocean currents, and absorbing heat and carbon dioxide. Antarctica even drives weather patterns in Australia.

Some people think of Antarctica as a safe, protected wilderness. But the continent’s plants and animals still face numerous threats.

Chief among them is climate change. As global warming worsens, Antarctica’s ice-free areas are predicted to expand, rapidly changing the habitat available for wildlife. And as extreme weather events such as heatwaves become more frequent, Antarctica’s plants and animals are expected to suffer.

What’s more, scientists and tourists visiting the icy continent each year can harm the environment through, for example, pollution and disturbing the ground or plants. And the combination of more human visitors and milder temperatures in Antarctica also creates the conditions for invasive species to thrive.

So how will these threats affect Antarctic species? And what conservation strategies can be used to mitigate them? Our research set out to find the answers.

What we found

Our study involved working with 29 experts in Antarctic biodiversity, conservation, logistics, tourism and policy. The experts assessed how Antarctica’s species will respond to future threats.

Under a worst-case scenario, the populations of 97% of Antarctic terrestrial species and breeding seabirds could decline between now and 2100, if current conservation efforts stay on the same trajectory.

At best, the populations of 37% of species would decline. The most likely scenario is a decline in 65% of the continent’s plants and wildlife by the year 2100.

The emperor penguin relies on ice for breeding, and is the most vulnerable of Antarctica’s species. In the worst-case scenario, the emperor penguin is at risk of extinction by 2100 – the only species in our study facing this fate.

Climate change will also likely wreak havoc on other Antarctic specialists, such as the nematode worm Scottnema lindsayae. The species lives in extremely dry soils, and is at risk as warming and ice-melt increases soil moisture.

Climate change won’t lead to a decline in all Antarctic species – in fact, some may benefit initially. These include the two Antarctic plants, some mosses and the gentoo penguin.

These species may increase their populations and become more widely distributed in the event of more liquid water (as opposed to ice), more ice-free land and warmer temperatures.

So, what to do?

Clearly, current conservation efforts are insufficient to conserve Antarctic species in a changing world.

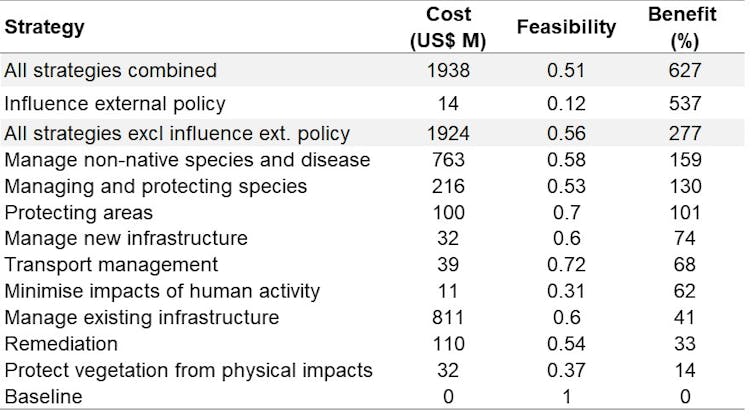

The experts we worked with identified ten management strategies to mitigate threats to the continent’s land-based species.

Unsurprisingly, mitigating climate change (listed as the “influence external policy” strategy) would provide the greatest benefit. Reducing climate change to no more than 2℃ of warming would benefit up to 68% of terrestrial species and breeding seabirds.

The next two most beneficial strategies were “managing non-native species and disease” and “managing and protecting species”. These strategies include measures such as granting special protections to species, and increasing biosecurity to prevent introductions of non-native species.

How much would it all cost?

The United Nations’ COP15 nature summit concluded in Canada this week. Funding for conservation projects was a core agenda item.

In Antarctica, at least, such conservation is surprisingly cheap. Our research found implementing all strategies together could cost as little as US$23 million per year until 2100 (or about US$2 billion in total).

By comparison, the cost to recover Australia’s threatened species is estimated at more than US$1.2 billion per year (although this is far more than is actually spent).

However, for the “influence external policy” strategy (relating to climate change mitigation) we included only the cost of advocating for policy change. We did not include the global cost of reducing carbon emissions, nor did we balance these against the much greater economic costs of not acting.

As Antarctica faces increasing pressure from climate change and human activities, a combination of regional and global conservation efforts is needed. Spending just US$23 million a year to preserve Antarctica’s biodiversity and ecosystems is an absolute bargain.

Jasmine Lee received funding from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment, an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship, and the Australian Antarctic Science Program (project 4297).

Iadine Chadès receives funding from the NSW Department of Planning, Industry and Environment (Saving our Species program, the Biodiversity Conservation Trust), the Queensland Department of Environment and Science, the NHMRC Centre of Research Excellence (CRE) SPECTRUM, and from the Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence Future Science Platform (CSIRO).

Justine is funded through the Australian Research Council Special Research Initiative – Securing Antarctica's Environmental Future. She has previously received funding from the Australian Antarctic Science Program. She is also a director of Homeward Bound Projects Pty Ltd and a director of the Landscape Recovery Foundation. Justine was employed by the Australian Antarctic Division as a Principal Research Scientist in 2022, on a part time appointment

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.