SOME songs paint vivid pictures. Few songwriters have combined the seemingly mundane – the worker on a telephone pole or the man leaving quietly in the early morning – with romance and poignancy as exquisitely as Jimmy Webb.

For more than 50 years, that name has been engraved on the roll call of great American songwriters. The youngest person ever inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, Jimmy Webb’s contribution includes classics like By The Time I Get To Phoenix, Wichita Lineman, Galveston, and Macarthur Park.

Winning his first Grammy at the age of 21 for Up, Up and Away, he had already paid his dues as a teenage songwriter with Jobete, the publishing arm of Motown Records. His ambition to have a life in music stretches back even further, however.

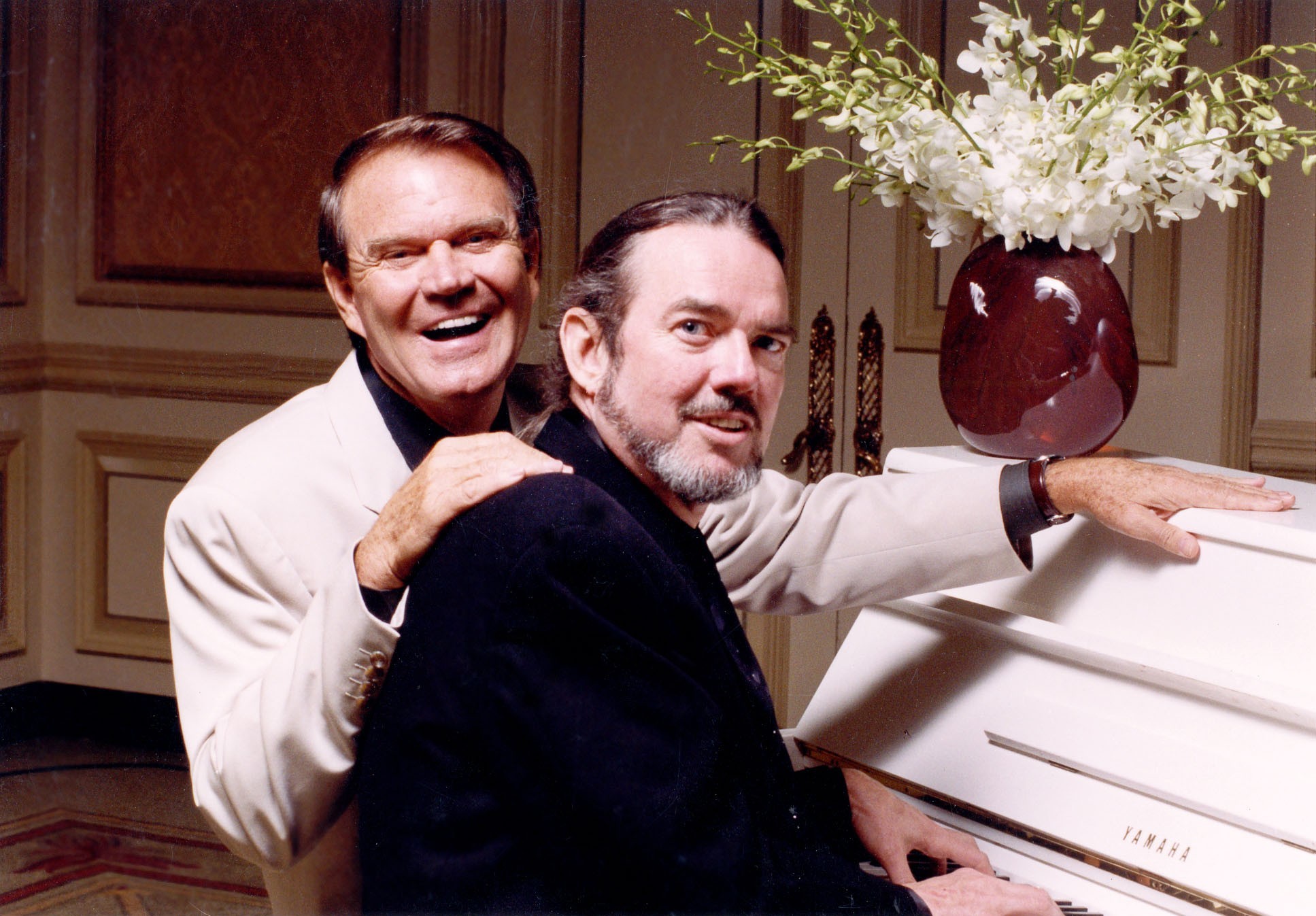

The son of a Baptist minister, Jimmy was encouraged to learn piano by his mother. He began making up songs as a child and at the age of 14, heard a song on the radio called Turn Around, Look At Me, performed by Glen Campbell.

“Something changed in me that day,” he says. “Right there in our house in Laverne, I got down on my knees. I said, ‘Dear Lord, please let me one day write a song for Glen Campbell, please make it a hit, and please make Daddy move to California to make it happen.”

All these things did happen and it’s one of the pivotal anecdotes in his show, An Evening With Jimmy Webb, which the 75-year-old brings to the Queen’s Hall in Edinburgh on June 3.

He laughs: “I usually say to the audience that I also asked him to make me a great singer and a superstar… Ah damn it, I was on a roll there.”

When the Webbs moved to Southern California in 1964, he studied music. When his mother died the following year, his father returned to Oklahoma, giving his son $40 and a warning that songwriting would break his heart. The same year the first commercial recording of one of his songs was released, My Christmas Tree by The Supremes.

Since he last played in Scotland in 2016, he released a memoir, The Cake and the Rain. Does this make his choice of stories for the shows more difficult?

“Well, it might be a bit like pulling back the curtain to reveal the magic trick, but it’s really a story jukebox,” he says. “As I’m going through the show, I maybe remember one that I haven’t played for a long time so I hit that button.

“The stories are all there; it depends on the night which make an appearance. It’s just me, a piano, my songs and my stories so I can change it up to make it interesting.

“I have an intelligent audience and they’ve done their homework – and particularly in Scotland, where they really know how to sing.”

Jimmy is well aware of how songs can affect an individual, and in 2019 he released an album called Slipcover, performing songs by everyone from Billy Joel to Randy Newman to more obscure tracks such as The Left Banke’s Pretty Ballerina.

“There are some songs that reach deeper into the psyche than others. Often we don’t know why a song has such a powerful effect on us, but we do know that when it comes on the radio, everybody has to shush. With some of those songs I’ve had to pull over while driving because I couldn’t concentrate.”

The phrase “the soundtrack to a life” is never more true and for Jimmy, songs like Stevie Wonder’s All In Love Is Fair was an antidote to what he calls “the craziness of the time when cocaine was the most important thing in my life”.

“I haven’t drunk alcohol, smoked or done any drugs for years, so I’m really talking about ancient history here, but I’m still human. But that song is part of a time, so it’s one that causes a severe emotional reaction. Some songs really ache.”

There’s little doubt that much of the audience feel that gut-wrenching yearning when they hear the intro to Wichita Lineman. With the distance of time, can he look at these songs as entities that he has let loose into the world, even if some, like Macarthur Park came from very personal experiences?

“Well, it’s a good question and it’s certainly appropriate because after years of performing something, sometimes I wonder whether I need to confront it. You always have to remember that with something like By The Time I Get To Phoenix, there could still be people that haven’t heard the song, alongside real dyed-in-the-wool fans. I really can’t consider a half-assed version, just because I’m overly familiar with it.

“I can shake up the arrangement a little by introducing some new ingredients. It could be a new chord, or a different interlude between the verses. It could be a different intro or intro but that level of familiarity means I can be constantly reinventing it.”

THERE’S a sophistication to the songs of Jimmy Webb, with many that straddle genres effortlessly but are classics in each. As a composer, lyricist and arranger his songs are wholly his, which makes him more precious to his musically literate audience – one that appreciates the access that they’ve enjoyed at previous concerts.

“I’m hoping it will be the same now, but certainly before Covid one of my favourite parts of the night was to meet them. To shake hands and do a little hugging and generally make myself available for signing and photos. They are really decent folk, intelligent folk, and extremely tuned into the musical nuances.

“Also, everybody has a story and I think that they should have an opportunity to tell it. So I listen to their stories and I find it that a lot of them are musicians, have been musicians, or were raised by musicians. Or they’re just someone who is affected by my music, I mean affected to the point of tears. They’re a sensitive group and I love them.”

He is aware of that responsibility, but also that hearing so many stories of how his songs have been pivotal at the most significant moments of a life, can inflate an ego.

“I have to remind myself, ‘at midnight you’re going to turn back into a pumpkin kiddo!’.”

Jimmy Webb plays the Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh, on Friday, June 3. www.jimmywebb.com