A goaltender's main job is to shut the door. Twenty-nine years ago, Manon Rhéaume swung one open wide for women across sports.

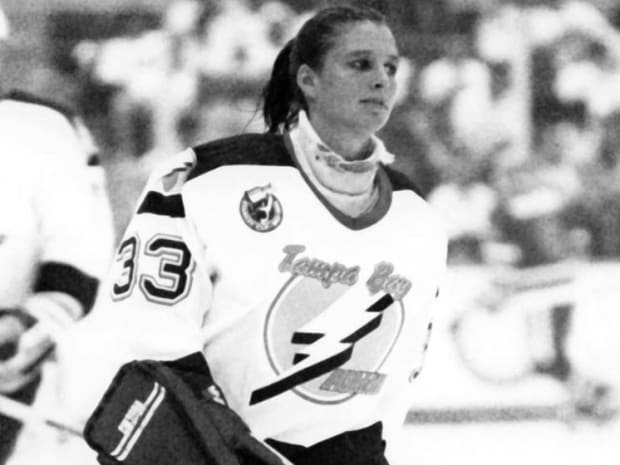

When Rhéaume skated onto the ice for the Lightning during a preseason game on Sept. 23, 1992, she became the first—and still only—woman to play in the NHL. The native of Lac-Beauport, Quebec, made seven saves on nine shots against the Blues. But Rhéaume, who was just 20 years old at the time, had no idea what an impact that moment would make. She was too busy battling butterflies.

“It was the most nerve-racking moment of my life,” she says now. “I knew my performance was so important.”

Rhéaume had been a hockey trailblazer long before the Lightning called her. At 11, she became the first female goaltender to play in the prestigious Quebec International Pee Wee Hockey Tournament. She played well and proved to be prophetic. When asked by reporters if she thought girls should be allowed to play hockey at a higher level, Rhéaume replied, “One day, a woman will make the National Hockey League, if no one prevents her.”

Shortly after the tournament, Rhéaume was signed to the Trois-Rivières Draveurs of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League for the 1991–92 season, becoming the first woman to play major junior hockey in Canada. A Lightning scout spotted her playing in the QMJHL and sent video of her to general manager Phil Esposito. Esposito, a Hall of Famer, thought the goalie looked a little small, but he liked the skill level he saw. He was surprised to find out that she was a girl—and decided to bring her to Tampa for a tryout. The 5-foot-7, 130-pound Rhéaume had the third-best goals-against average of any Lightning goalie during preseason camp.

Courtesy of Manon Rheaume

After her brief stint with Tampa Bay—she played in another preseason game against the Boston Bruins in 1993—Rhéaume competed in the International Hockey League for several teams. She won gold medals with Team Canada at the 1992 and ‘94 Women's World Championships, a silver at the ‘98 Winter Olympics in Nagano—and a piece of hockey history.

Rhéaume, now 49, is the mother of two hockey players—her oldest is also a goalie—and oversees the Little Caesars girls’ hockey program in Detroit. In October 2020, she collaborated on a children’s book, Breaking the Ice, that chronicles her life and career. A feature film based on her life, Between The Pipes, is currently in development. And Rhéaume was recently honored with a statue in her hometown of Quebec City.

GoodSport spoke with Rhéaume about whether we’ll ever see another woman play in the NHL, why watching her son play goalie is harder than playing herself and how even though her brush with the NHL was brief, Rhéaume continues to inspire countless kids to follow in her skate tracks.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

GoodSport: Your book opens with a scene of you, shortly after your 5th birthday, asking your dad if you can play goalie on his team. You parents hesitate, but your brothers chime in to support you and convince him. How much did playing against your brothers help you?

Manon Rhéaume: I owe my brothers everything. They’re the reason I started playing hockey. They needed a “shooter tutor,” so they made me dress up as a goalie. If I wanted to play with them, I had to get in net. But they always supported me. My younger brother, Pascal, ended up winning the Stanley Cup with New Jersey. We were each other’s biggest fans. We still are.

GS: The book also mentions that your dad encouraged you to play, but asked you to put on your mask before you skated out onto the ice. Why did he want you to do that?

MR: My dad knew that it was not going to be easy for me. I remember him shooting pucks at me in the basement the week before my first game. I took a puck off my shoulder and complained that it hurt. My dad said, “Manon, get used to it. If you want to do knitting, it’s not going to hurt. But if you want to play hockey, sometimes the puck’s gonna hurt.”

The lightbulb kind of went on for me, and I thought, OK, if you really want to do this you’re going to have to work hard and to fight through stuff. My dad told me, “People aren’t ready to see a girl play on a boys’ team yet. But don’t let that stop you.” So I put my mask on before I stepped on the ice. Everybody was just so excited to see a new goalie, and by the time they realized I was a girl it was too late to complain about it.

After I started playing and started having some success, some of the parents were jealous. I remember my dad telling me, “You’re not going to play goalie next game because another kid on our team wants to play in net.” And I said, “Why, now that I started having success, do other people want to play my position?” My dad said, “Just trust me.” The other parent had told him, “My kid is so good when he plays in the driveway. I think he should play goalie.” So my dad started him. We lost the game 13–3. After the game, all the other parents went to my dad and said, “We want your daughter back.” My dad just knew how to make sure that people accepted me. And that’s how I was able to make it to where I did.

GS: Some people said that Phil Esposito’s decision to give you a tryout was a publicity stunt, an attempt to drum up interest in Tampa’s new expansion team. You knew this and still welcomed the opportunity. Why?

MR: It didn’t matter to me why I was invited. When I was younger, so many people had said no to me—and wouldn’t allow me to play at a higher level, like AAA—because I was a girl. So if this time someone said yes to me because I’m a girl, I was going to take that opportunity. At the end of the day I still had to prove myself on the ice.

GS: When did you start to realize how much of an impact you had made?

MR: Not until I got older. When people would come up to me and say, You’re such an inspiration for my daughter. Or, My son did a project on you in school. Mike McKenna, a former NHL goalie who is now a TV analyst for the Golden Knights, interviewed me for his podcast a few years ago. He told me, “When I saw what you did, I told myself that I could do it too.” To know that I even inspired young boys to go after their dreams … that’s when I realized that maybe it was a big deal, what I did.

GS: In June, 16-year-old goaltender Taya Currie became the first girl drafted to the Ontario Hockey League—and one of a handful of women to play in a major junior league, as you did. You reached out to Currie after she was selected by the Sarnia Sting. What did you tell her?

MR: First, I wanted to congratulate her, because it was such a great accomplishment. The way she was playing, she deserved it. It was not, “Oh, we’ll invite you to camp.” She got drafted.

I also told her that I’m here if she ever needs to talk with someone. When I went to Tampa, I had nobody to talk to who could understand what I was dealing with. Taya played in a tournament in Michigan with her boys team when she was younger. I was coaching my youngest son’s team at the same tournament. She asked me to take a picture with her. When I talked with her again, after the draft, she reminded me and showed me the photo.

It’s so different today than when I played. Women are way more accepted in male-dominated sports—which is really cool—and at her position. Women are getting opportunities, but it’s because of their talent.

Courtesy of Manon Rheaume

GS: Women’s hockey has come a long way during your lifetime, and girls’ hockey is among the fastest-growing youth sports in the U.S. What still needs to happen for women’s hockey to reach its full potential?

MR: We need the support of the NHL—like the NBA gives the WNBA—and the support of NHL teams. You see it with the PWHPA [Professional Women’s Hockey Players’ Association]. The NHL teams that are supporting what the PWHPA is trying to do, promoting its events, are really helping because they have marketing and sponsorship behind them. Imagine if a women’s team could share some of that?

GS: You’re still the only woman to play in the NHL, NBA, MLB or NFL. What do you think needs to happen for a woman to break through in any of these sports? Or is the answer developing women leagues?

MR: Of course, developing women’s leagues is important. Because even if another woman does play pro baseball or basketball or hockey—any of those sports—with men it wouldn’t necessarily help the rest of the women out there get more opportunities. It would be great for that person. It would be great for the sport. But what about all the other women who play the sport? They need a place to go.

Look at all those women who play on the national teams for Canada and the U.S. They are amazing hockey players. Imagine if they were able to not only play four years of college hockey, but also continue to train at a high level and play every day like the men do—and not have to have three or four other jobs just to be able to do all of it. That’s what needs to happen.

GS: So the first step is paying players a livable wage?

MR: Right. It’s not that they’re looking to make $5 million to play hockey. They just want to not have to work a 9–5 job and then only be able to train late at night. They want to be able to get on the ice every day. We’re talking about Olympians, people who represent our country. They need to be the best that they can be. They need a place where they can actually make a living playing hockey.

GS: Your older son, Dylan St. Cyr, is a goalie. [After playing three seasons at Notre Dame and earning a degree, he will play for Quinnipiac this season.] What’s harder, playing goalie yourself or watching your son play goalie?

MR: It is absolutely harder to watch your child play goalie. When you choose to play goalie, it’s because you like the pressure. You can control your preparation. You can control your emotions. You can control your destiny. But when it’s your kid, you have zero control.

That first time that Dylan played in a state playoff final, I called my mom and said: “I woke up this morning with butterflies in my stomach. Am I crazy?” My mom said, “It’s payback time.” I was like “OK, I get it now.” My poor mom. Not only was I a goalie, I was the only girl playing with all guys. And she knew that everybody would judge me even more.

GS: Your younger son also plays hockey. Is it different watching him?

MR: Dakoda is playing AAA hockey, U15. He’s a defenseman. I always look forward to watching both of my kids play. But when I go watch Dylan, it’s not fun for me. When I watch Dakoda, I can actually enjoy the game.

GS: Why did you decide to start coaching?

MR: Darren Eliot, who used to be an NHL goalie, approached me. His son was playing with my sons in the Little Caesars hockey program. He asked if I was interested in running the girls’ program. It was a project and a challenge: to build a program from the bottom up. Watching my sons play, and coaching them along the way, I saw a lot of things that I felt could be changed about youth hockey. It was really great to be part of building something. I coach the youngest team, the U-12s. The girls that I started with, five years ago, they’re now on the U-16 team. They just won the national championship. About 13 girls from that team will probably go on to play at a D-I level. We really focus on developing the kids, and not sacrificing that development just to win games. By doing this, they ultimately do win and have a lot of success, and the girls get scholarships to college, which is amazing to me, because those kinds of opportunities were not there when I played.

GS: One of the players you coached, Kendall Coyne-Schofield, has gone on to win gold medals at both the world championships and the Olympics, and was hired by the Blackhawks last year as a player development coach, becoming the first woman to serve in that role for the team. Did you see her potential right away?

MR: I got a chance to coach Kendall, and I knew right away that she would go far in hockey—and in life, just because of her work ethic and her drive. She was the best player on my team, and the hardest worker, every shift on the ice. She was just so driven, and she made everybody else around her better. And not only is she a successful hockey player, she is amazing on TV, and she’s also working with the Blackhawks now. I’m not surprised to see all of her success.

GS: Who inspires you?

MR: When I was younger, because I didn’t see any women playing the game, I looked up to NHL players like Quebec Nordiques goalie Daniel Bouchard. Now, I love seeing women succeed in their field. At the World Junior Championship last winter, Theresa Feaster was the video coach for the U.S. team. She was the first woman to be on the coaching staff for USA hockey for a world championship. The head coach who hired her said, “We’re all happy that she’s the first female. But she’s not here because of that. She’s here because of her talent and because she’s great at her job.” That inspires me, seeing women like her getting opportunities because they’re good at what they do. Those are the stories that I love to hear—Taya getting drafted because of her talent. Kendall participating in the fastest skater competition at the NHL All-Star Game. It was so cool to see the guys watching Kendall, and realizing how talented and how fast she was. Those are the things that get me excited and inspire me.

GS: What’s left on your bucket list?

Aimee Crawford is a contributor for GoodSport, a media company dedicated to raising the visibility of women and girls in sports.