The Muhammad Ali Legacy Award celebrates an individual whose dedication to the ideals of sportsmanship has spanned decades and whose career in athletics has impacted the world.

Everything changed for Allyson Felix when a potentially deadly diagnosis for her and her infant daughter led the baby to the NICU. It was November 2018, and Camryn had been born two months early, via emergency C-section, at just three pounds, eight ounces.

“For the first time in my entire life, track was on the back burner,” Felix says. “I wasn’t concerned about running my next race. I was concerned about my daughter living and for us to be able to be together as a family.”

While they both survived that frightening time, Felix would never be the same. The course she’d chart from that moment would transform the track star—known for always keeping her gaze focused on the lane ahead—into an activist and path-breaking entrepreneur.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Until then, Felix had preferred to let her performance on the track speak for itself. Speed that built with a hum. Legs and arms that pumped with smooth fluidity. Explosions of acceleration that quieted her competition. Then a flash of a bright smile, a wave to her adoring fans.

It had been like that since she showed up to track tryouts as a 15-year-old, basketball-loving freshman at Los Angeles Baptist High and astounded coaches with her raw speed. She was a rare breed of athlete—one that not only lived up to the early hype, but also far exceeded expectations. She won her first Olympic medal, a silver in the 200 meters, at the 2004 Games in Athens at just 18 years old. Her total career haul after retiring at 36 in July ’22: a women’s track and field record 11 Olympic medals (seven gold) at five consecutive Games; 10 national titles, in three different events; and 20 World Athletic Championship medals (14 gold), making her the most decorated athlete in the event’s history.

In truth, though, change had started to stir in Felix in the months before Camryn’s birth. At six months pregnant in 2018, she trained in the darkness of dawn so no one could see her growing baby bump. She didn’t want Nike, her sponsor since ’10, to find out that she was expecting. Felix’s contract had ended in December ’17, just before her pregnancy, and she wanted to use her renegotiation to ensure she could start a family without losing her livelihood. When she asked Nike for a guaranteed protection of her salary around the months surrounding childbirth, should she have a baby, she says Nike declined. While still in negotiations, Felix got pregnant. She concealed as much as she could, for as long as she could, but then, at a routine doctor’s appointment, Felix was diagnosed with severe preeclampsia, high blood pressure that can be fatal in pregnancy. Camryn remained in the NICU for about a month before Felix and her husband, Kenneth Ferguson, took her home.

When Nike finally proposed a contract in which the company agreed to protect her salary for 12 months after giving birth, she says she told them she’d accept only if the terms were tied to maternity, setting a precedent for all female athletes the company sponsored. Nike declined. So while she recovered from a traumatic birth to get back to race form as soon as possible, she still didn’t have a contract.

Bob Martin/Sports Illustrated

The whole experience was lonely—but a few months later, something happened that made her realize she wasn’t alone at all. In May 2019, a viral New York Times investigation revealed how Alysia Montaño, an Olympian in the 800 meters, had left Nike in ’13 because the company told her that if she got pregnant, it would pause her contract until she could race again. Her next sponsor, Asics, also threatened to stop paying her after she had her daughter in ’14. Kara Goucher, another Olympian, told the Times that Nike had stopped paying her when her son was born in ’10, until she began competing again. When her son was hospitalized with an illness at three months old, she had no choice but to return to training and leave him, to earn her paycheck to support her family.

These stories confirmed Felix’s feeling that something was wrong in her sport on a bigger scale. “I felt a strong pull that I needed to be involved as an athlete who was going through a really difficult time, in real time,” she says.

Bill Frakes/Sports Illustrated

On top of that, her agent had recently told her that Nike wanted her to be in a campaign for the upcoming 2019 Women’s World Cup. Promoting a company’s message of women’s empowerment while being told by the same company that athletes who became mothers weren’t due any financial protections? That felt dishonest to Felix. Still, it wasn’t easy for the formerly quiet athlete to speak up.

“It was so outside of my comfort zone. I’m a person who is shy by nature and I don’t like to rock the boat. So it was really, really difficult to be able to find that place to come forward and to share what had been going on,” she says. Ten days after Montaño’s op-ed was released, Felix penned her own story in The New York Times.

And because she was Allyson Felix—a marquee name who had never spoken out on anything controversial before, who had just shown up, done the work and added to her medal collection for nearly two decades—the whole world paid attention.

Goucher saw the public reaction shift. “When Alysia did her video, and I shared my story, it got people talking, but the response was [half] support,” says Goucher. “But when Allyson came out, the impact was immediate.”

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

Her story went viral. Media coverage of the issue exploded. A congressional inquiry was launched into Nike’s practices. And within months, Nike announced a new maternity policy that guaranteed 18 months of pay for sponsored athletes who have children. Other athletic apparel companies have since followed suit. “There’s just no way that maternity contracts could have changed the way they did without her influence. Her voice was so powerful,” Goucher says.

Montaño was surprised when she read about Felix’s contract struggles. She’d assumed Felix, with all her medals and marketing potential, would “have all the support in the world.” When Montaño came forward, she had no sponsor and hadn’t run competitively in two years. “I shared because I had nothing to lose,” she says.

Meanwhile, as a long-distinguished athlete still competing at the highest level, Felix was jeopardizing her career by speaking out. “She did have that reputation of no controversy, nothing negative,” Goucher says. “She did have a lot to lose. She risked [it] to do what was right.”

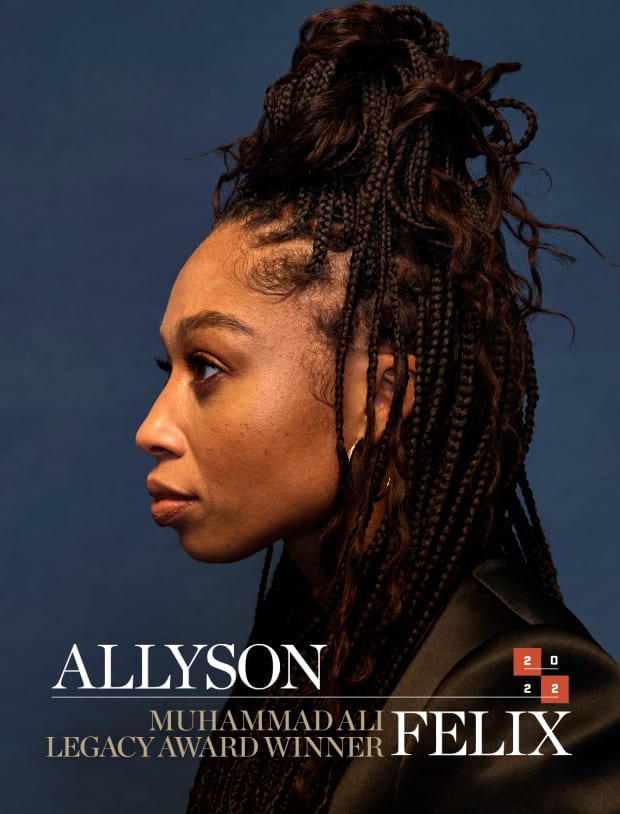

Since that moment, Felix hasn’t stopped using her voice, and her power, for other mother athletes—and mothers everywhere—to have better work protections, paid leave, improved health outcomes and access to affordable childcare. This tireless work and fearless advocacy are why she is this year’s Sports Illustrated Muhammad Ali Legacy Award winner.

After she went public, Felix didn’t sign another contract with Nike. Instead, she paved a new path entirely, becoming the first athlete to be sponsored by Athleta, the women-run sports apparel company owned by Gap Inc. (Simone Biles would follow.) By July 2019, just eight months after Camryn’s birth, Felix had returned to competition, earning her 12th and 13th world championship gold medals in the lead-up to the U.S. Olympic track and field trials for the Tokyo Games. But she was still without a footwear sponsor. So she and her brother, Wes Felix, recruited Natalie Candrian, a former Nike and Adidas designer, to create running spikes for Felix less than a year before the Games. The super light, 3.9-ounce baby-blue spikes were assembled in Portland; she trained in samples. They officially announced the formation of Saysh, a footwear and lifestyle company, in June ’21. The name is a take on seiche waves, the type of standing swells that can form in an enclosed body of water, like a lake—exactly the ripples Felix is hoping to make in the sports world.

Kohjiro Kinno/Sports Illustrated

“[Saysh] exists because I believe that women deserve better,” Felix says. As she dove into the details of manufacturing, Felix was astounded to find out that most athletic sneakers are made based on the mold of a man’s foot, whether they’re marketed as men’s or women’s. The Saysh One, the company’s first lifestyle sneaker, was specifically designed to fit a woman’s foot and launched in September 2021. Saysh’s first running and training shoes are expected in ’23. Felix sees Saysh as a way to start changing the status quo throughout the sports apparel industry; in April the company launched a groundbreaking return policy, allowing women to exchange sizes if their feet change during pregnancy. But Felix is also thinking bigger. “Even beyond the shoes, we need companies that see women, and that starts from within,” she says. “It starts with the culture and all of our team being aligned around that cause—that women should not be overlooked and that we’re gonna do better by them.”

In Tokyo in 2021, at age 35, Felix earned her final two Olympic medals: a bronze in the 400 meters and a gold in the 4 x 400-meter relay, both with Saysh spikes on her feet. But Felix did much more than wear messages of empowerment at the Games: With the help of Athleta and the Women’s Sports Foundation, she launched a program to give more than $200,000 in childcare grants to mom athletes traveling to competitions in 2021, including six other Tokyo Olympians and Paralympians.

Hannah Peters/Getty Images for World Athletics

Focusing on childcare was a natural next step for Felix. When she returned to running after her daughter was born, she realized not only how hard it was to compete with a baby in tow, but also how expensive it was. “I feel really blessed that I had the resources to travel the world and bring someone to help me,” she says. “But I was thinking about the other families who weren’t able to. I have a lot of friends who ended up having to shorten their careers.”

After the Olympics, Felix joined the board of &Mother, the nonprofit Montaño cofounded to drive change for mothers in sports. Together, with Athleta, they built upon the grant program from the Olympics to offer free, on-site childcare at track and field events in 2022, including this summer’s U.S. Outdoor Championships. Montaño says working with Felix and her supporters has meant a bigger impact—and faster change. “We wouldn’t have had the ability to so quickly amplify our story if Allyson did not share hers in such a way,” Montaño says. “She was willing to get her hands in there and use her network and partners to help us do the work.”

Goucher says runners who are also mothers have been portrayed differently since Felix began her advocacy. “When I had my son, it was almost like I had to prove that I didn’t have a kid. The message was: ‘Don’t be a mom when you’re out running.’” Now, she says: “There’s moms on the track with their babies, and it’s looked at as a human enhancer, rather than an athletic disadvantage.”

And women in other sports are feeling the shift, too. Since Felix spoke out, the WNBA and its players union have renegotiated their contract to include, for the first time, paid maternity leave and childcare expenses for players. And in historic contracts ratified this year, the U.S. women’s national soccer team players secured not only equal pay, but also six months of paid parental leave, while the National Women’s Soccer League players secured eight weeks. Athletes Unlimited, which runs women’s pro softball, lacrosse, basketball and volleyball leagues, offers unlimited paid parental leave and childcare. These protections have likely helped encourage more women athletes to not put off having children until their careers are over. Meanwhile, stars like Alex Morgan, Crystal Dunn and Skylar Diggins-Smith are now proudly bearing the title Athlete Mother.

Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP/Shutterstock

Marking progress is always heartening, but in today’s divisive political environment, issues affecting women’s health and maternity decisions can also seem more controversial than ever. In the face of broader setbacks—like proposed universal childcare and parental leave legislation failing to pass through Congress, and the Dobbs decision from the Supreme Court, striking down Roe v. Wade—Felix says she is not discouraged, but more motivated. “I think that just fires me up more. These are things that we have to get done, and we can’t afford to go backwards,” she says.

Felix says since the beginning of speaking up, she’s done this work for—and with—her peers and those who came before her. “It makes me so excited when I see so many women having children, coming back to sport [and] being supported. That’s what this has all been about.”

In an extremely Allyson Felix example of selflessness, she ran her last competitive race (in a supporting role) eight days after she was supposed to have retired. After winning a bronze at the World Championships in July in the mixed gender 4 x 400-meter relay, she’d already headed back to Los Angeles and what she thought was retirement. But when coach Bobby Kersee suddenly needed a runner, she hopped on a plane back to Eugene, Ore., to hold down a leg of the preliminary women’s 4 x 400-meter relay. After qualifying the team for the final, Felix looked on while four young track stars captured the gold medal for the U.S. Those four—20-year-old Talitha Diggs, 22-year-old Abby Steiner, 22-year-old Britton Wilson and 23-year-old Sydney McLaughlin—have Felix to thank for getting them into the final, yes, but also for creating a world where being a woman runner doesn’t mean having to delay having a family, or hide a pregnancy, or fear for how to care for her kids while traveling for work.

With competitive racing behind her, Felix knows her athletic career is done doing its talking, but that doesn’t mean she’s done using her voice.

“I always think about my daughter and the world that she’s gonna grow up in, and I would love for that to be a more equal world,” Felix says. “I would love for her to not have any limitations or think about anything twice because she’s a girl. So those are all things that continue to push me and to know that there’s so much more to do.”