In “On Exactitude in Science,” a 1946 short story from the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, a fictional 17th century chronicler describes a guild of cartographers who make ever-bigger maps until, eventually, they create a “Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it.” As tastes change, later generations declare the map “Useless” and leave the great work to wither in the desert sun, where “Animals and Beggars” live within the map’s “Tattered Ruins.” The brief tale manages to probe the nature of inquiry and spoof the history of empire, quite a feat for a piece that’s only a paragraph long.

Watching the films of Alejandro González Iñárritu, the multi-Oscar-winning writer-director behind The Revenant, Birdman, and Babel, can feel like watching both Borges and the cartographers work at the same time. He’s a man who often seems to be attempting to make artwork that’s nearly as big as life itself and fully aware of the impossibility of truly doing so, all of this further complicated by the challenges, again, fully acknowledged within the work, of telling stories about identity and history as one of the few Mexicans given a grand Hollywood stage and the budget to match.

There’s his so-called “Death Trilogy” of Amores perros (2000), 21 Grams (2003) and the aptly named Babel (2006), where loosely related collections of stories weave in and out of each other, on increasingly grander scales, across time zones and continents, like currents in a great ocean. There’s Birdman (2014), about a has-been superhero movie star, played by a silver-haired Michael Keaton, who once played Batman, slowly losing his mind as he battles critics and attempts to prove his artistic bonafides on Broadway. The Revenant (2015), meanwhile, is about far less theoretical clashes, set during a frigid winter among the churning violence and cultural collision of 1820s Dakota territory.

With his trippy, loosely autobiographical new Netflix epic Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths and his traveling virtual reality installation CARNE y ARENA: Virtually present, Physically invisible, Iñárritu is taking the biggest swings of his career. As he told The Independent in an in-depth interview, both projects, which tackle the swirl of US-Mexico history and migration, are his attempts to “liberate cinema” from traditional linear storytelling and probe the messier, more honest realms of human consciousness.

“Conventional storytelling is very limited,” he says. “It’s a construction. In the reality of our lives, our lives are built with random thoughts and fears and dreams and memories and worries for the future and ghosts from the past going on in our minds every day.”

It’s an experiment that, for CARNE y ARENA, won him his fifth Oscar, this one for special achievement in 2017, and has earned him some of the most mixed reviews in his career for Bardo, but Iñárritu is invigorated by the challenge.

“I’m trying to explore a mental landscape, to walk in the consciousness, where the juxtaposition of images and sound can create an experience,” he says. “You can call it the metaphysical experience or the lucid dream experience, where in a way those experiences transport you in not only on an intellectual level, but on a subconscious level to some state of mind…Even failing is better than not attempting.”

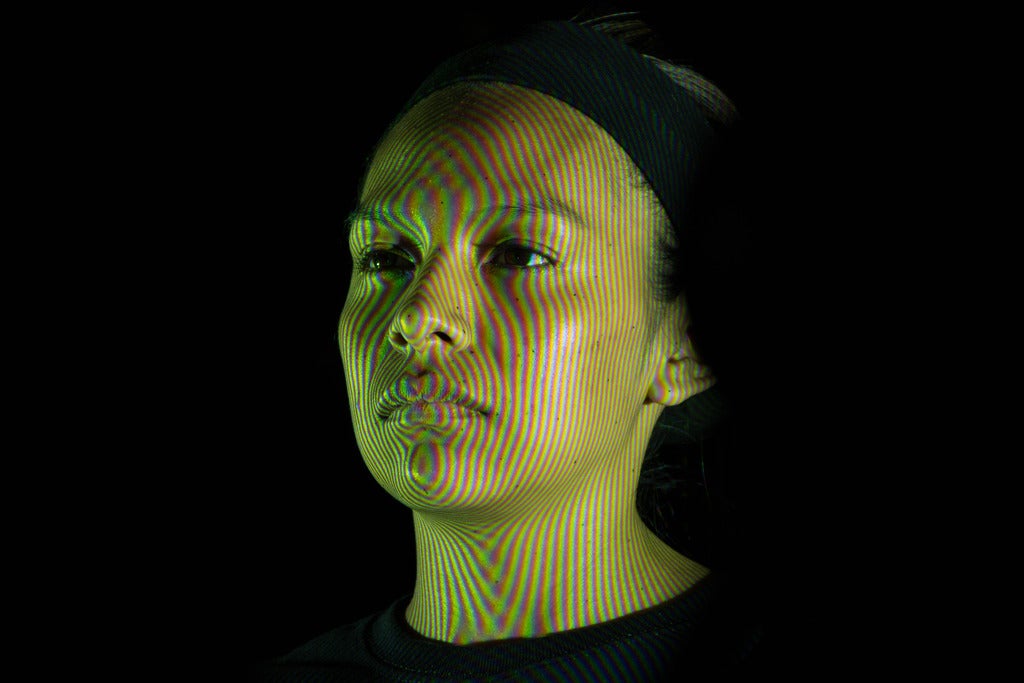

This fall, I visited CARNE y ARENA (flesh and sand in Spanish) on a quiet pier in a district of warehouses and factories in Richmond, California, across the bay from San Francisco. The exhibit’s sleepy setting contrasts with the rabbit hole journey it contains. The project is a somewhat unclassifiable combination of physical art installation, virtual reality film, and straight-from-the headlines embodied nightmare.

The installation, a collaboration with cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, producer Mary Parent, Lucasfilm’s ILMxLAB, and composer Alva Noto, takes viewers on a roughly half hour solo journey, joining a group of migrants as they travel from Latin America to the US, across the border and the borderlines of media and reality.

The experience begins in a frigid room modelled on a US Immigrations and Customs detention centre, where guests are encouraged to place their shoes in a metal hatch at the start, with no indication how you’ll ever get them back.

You know it’s not real, but stripped down, with the cold concrete on your bare feet, the spartan benches, and the piles of worn out shoes collected from the actual US-Mexico borderlands, you are instantly plunged into a state of powerlessness and dreadful anticipation. I couldn’t help but think of the other time I saw a pile of ghost shoes, at the former Auschwitz concentration camp in Poland, and of the long-running, deliberate efforts by US officials to shunt border-crossers away from sanctioned ports of entry towards more remote, fatal desert journeys as a method of cruel deterrence.

An alarm sounds. A red siren above a door indicates it’s time to go deeper into the labyrinth. Another jarring break with reality.

You’re standing in a large room, filled with real sand, illuminated by a ring of dusky-orange light. A technician quietly rigs you into a virtual reality headset, and you’re no longer alone. You wander through the space, which now appears to be a fully rendered 3-D desert just before dawn, with a party of animated migrants, motion-captured images of actual border crossers Iñárritu selected after interviewing hundreds of people at a Los Angeles migrant shelter.

The serenity of the desert, the starry skies, the chittering of insects – they don’t last. Headlights from a Border Patrol pickup blare across the darkness, malevolent tractor beams. You can’t help but try and hide behind a virtual cactus, but you know it’s no use. Your pulse begins to race.

Before you can catch your breath, agents in body armour are pointing guns in your face, screaming in English and Spanish. Hellhound search dogs bark at your heels. One of your party members, a senior citizen who speaks an indigenous language, appears confused and disoriented. Babies wail. A wobbly raft, overflowing with people, and appearing to be coated in black sludge, sails through view, as if the migrants of Latin America and Mediterranean enter a moment of quantum communion. If you walk too close to one of your compatriots, you see a brief flash of a giant, beating heart, as if you’re inside their chest, an inch from their soul.

Then, bam, the scene snaps back to desert emptiness, a clear beautiful day, and no sign of the lives or the legacies that brought people to this place and led them to be disappeared from it.

The final stop of the journey is a long hallway filled with recessed screens, where you stare eye-to-eye with the actual migrants whose story you’ve just tasted, as they explain in their own words why they braved so much to come to the US.

The tales are diverse. An El Salvadorian man fleeing gang violence. A Border Patrol agent who sees dehydrated, dying migrants in his nightmares. A mother, Carmen, whose son was born in Honduras and whose daughter was born in the US. “What does that make me?” she asks. Francisco, 22, who vows to give the US “all my talents,” despite the high price it asked for him to make it there. All these stories, however, point to the profound fracturing,of lives, identities, and morals at work in the US immigration system.

Iñárritu says he got the idea for CARNE y ARENA, the first VR film to premier at Cannes, as he saw “this orange monster called Donald Trump” rise to power, and watched as the media showed image after image of migrants as a faceless mass of humanity and even the most thoroughly researched works of journalism started to seem like just another grim, flat data point.

“Words or images in a way are not enough to make us understand such a complex reality. We rationalise it. We interpret those thoughts according to our system of belief, our religion, our social background, our nationality, or whatever you want,” he says.

“When I saw the opportunity of virtual reality, I saw the opportunity to bring more than words or images to create an experience, a sensorial experience where it hits your body,” he adds. “The body doesn’t lie. You don’t have to interpret it. It’s a primal frequency and sensation that you are impregnated with.”

As I stepped out of the installation, I felt a profound gratitude to be out of the darkness and constriction of the maze the director had built, and back in the sun, feeling a cool sea breeze on my skin. Across the bay, I could see Angel Island, ironically named if anything ever was, where immigrants, then Japanese and German POWs, were once detained, carving graffiti into the stone walls. It’s now a popular hiking destination. The installation was over, but the carceral architecture of US immigration hasn’t gone anywhere.

Bardo: False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths, which premiered in theatres last month and is now streaming on Netflix, tells an even more sweeping, meta-fictional story.

The film, Iñárritu’s first movie shot in Spanish in his native Mexico in 22 years, is named for the Buddhist concept of the bardos, a multi-stage, liminal state between death and rebirth. It follows Silverio Gama, an acclaimed Mexican director, on an ouroboros journey of his own. After achieving success in America, Gama returns to his home country to accept an award for his latest project: a “docufiction” about his life and Mexican history called…False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths.

The plot, though, is less the point than the world it exists inside. Throughout the film, the lines between Gama’s story, the images from his docufiction, past and present, bleed into each other seamlessly, until the boundary is beside the point.

Rooms fill with desert sand. A baby crawls back inside the womb, telling his parents he wishes not to be born because the world is “too f***ed up.” Amphibious axolotls swim in flooded train cars. Amazon attempts to buy a piece of the Baja peninsula. A US customs agent, who appears to be Mexican-American, tells Gama and his family, due to their visa status, Los Angeles is “not your home.” As the two argue about the nature of Mexican- and American-ness, guards in 1800s livery drag Gama away, kicking and screaming.

In one extremely charged image, the loosely fictionalized director climbs an Aztec pyramid horrifically piled with indigenous bodies and encounters Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, who claims to be the first true Mexican.

Critics have applauded the film for its jaw-dropping images. (I often think about a sequence in which, in the midst of the film’s intellectually tangled thicket, the pure joy of dance and music allows Gama to achieve a brief state of nirvana at a party, in a nautillus-shaped swirl of hands, as a crystalline a capella version of David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” seems to ring through the whole theatre.)

Others have criticised what The New York Times called Iñárritu’s “monumental ego” and the “exasperating, exhausting company” of being so thoroughly plunged into the director’s mind. Perhaps owing to such criticisms, the version of the film playing now is 22 minutes shorter than the cut that premiered at the Venice Film Festival. (The final version still runs nearly three hours.)

Of course, in Bardo’s hall of mirrors, all of these criticisms are thoroughly aired out in the movie itself.

In one scene, the film’s protagonist chases Gama through the desert, demanding his film reach a suitable end. The director, that is, the fictional one, Gama, sometimes mutes characters who go too hard on him. In one of the funniest and most pointed scenes in the movie, Gama’s old journalism colleague Luis, who stayed in Mexico and rose to become a prominent, if hacky, TV host, utterly eviscerates his old buddy at a party, lambasting the self-obsession and pretentiousness of Gama’s work.

Ironically, Iñárritu says that he felt none of the same encroaching creative anxiety around representation or critical reception as his fictional characters do when he was making his own hallucinatory film about the same subject matter.

“I’m not officially a cultural ambassador of my country,” he says.“I don’t have that burden and that responsibility. For me to create the way is to be free of that responsibility of political agenda or social work. If my work is free and represents honest things, it will capture that.”

If there’s one actual beef he has with his critics, it comes down more to genre. In a recent interview with the Los Angeles Times, Iñárritu argued some of the negative reactions to his film are influenced by a “racist undercurrent,” a perception that existentialist art is reserved for Europeans, while Latin Americans are confined to the ornate cage of “magical realism.”

As we wrapped up our conversation, Iñárritu argued he’s working from the long tradition of Latin America artists like Borges or Gabriel García Márquez, who took just as prismatic, ironic, and ambitious looks at reality as any European philosopher or writer.

“They always explore this possibility of having personal experiences, and once they are fictionalized, they are liberated from everything,” he says. “The personal, the universal. The fiction and the truth.”

“Everything you start navigating with a great freedom. That’s what I attempt. I attempt this with no rules,” he concludes. “That’s the very thing I wanted to express.”

It may not win him universal acclaim, but few could accuse Iñárritu of lacking ambition or honesty. As the director forges ahead into his explorations of false chronicles and illusive truths, it will be up to audiences whether his films wither in the sun as ambitious, useless relics, maps the size of the Empire, or whether they’re maintained as splendid pyramids, which the next generation will climb, considering the new perspectives they are afforded from such great heights.