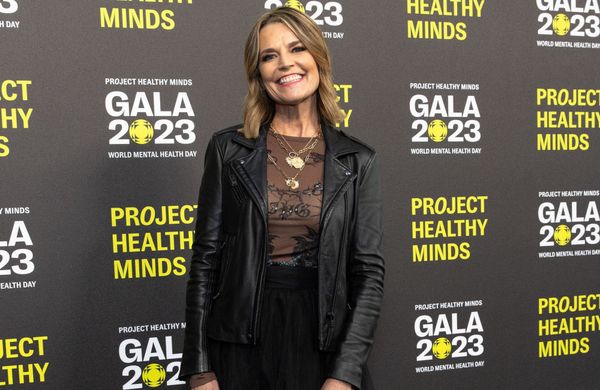

Poet and memoirist Christian Wiman was 39 when he was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. Now 57, he's endured many rounds of chemo, a bone marrow transplant and several experimental therapies over the past 18 years. He also turned to what he terms "God."

Though Wiman grew up in an evangelical church in West Texas, he spent many years as a self-described "ambivalent atheist" before finding religion again.

"I don't picture God at all. ... I don't think of God as an object at all," he explains. "I find it more helpful to think of God as a verb."

Wiman teaches religion and literature at Yale Divinity School and the Yale Institute of Sacred Music. His new book, Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair, uses memoir and poetry to explore themes of illness, love and faith.

Wiman's cancer has been in remission since the spring, but he says that living with illness for so long has shaped how he thinks about life. It's also taken away his fear of death.

"The truth is, when death hangs over you for a while, you start to forget about it," he says. "The only reason I was scared of death was my kids and my wife, of course. But for myself, that sort of visceral fear that I used to get of my own life ending, that visceral animal fear — I don't feel that at all."

Interview highlights

On the worst kind of despair

In my experience, the worst despair is meaninglessness. It's not necessarily thinking that you're going to die. It's the feeling that life has been leeched of meaning. That's the worst. And physical pain actually doesn't bring that all in. That can come on any time. In my experience, you can have physical pain and still experience joy. Joy can occur in the midst of great suffering. The kind of difference between joy and happiness — we're not happy in the midst of great suffering, but we can still experience these moments of joy. I think there are a couple of different kinds of despair. The despair that you feel in physical pain is not existential. It's remediable with the drugs. When they don't work, and I've had periods when they don't work, then you really do fall into a kind of irremediable despair.

On turning to faith because of love and illness

People mock the fact that it takes a crisis to bring us to God. They say there are no atheists in foxholes — of course there are plenty of atheists in foxholes. But the fact is, it takes a hell of a lot for us to change a coffee habit or something, and so to make an existential change in your life, you sometimes need to be really taken by the throat. And for me, that actually happened when I fell in love and not necessarily when I got cancer. My wife and I actually started to pray shortly after we met each other. And it was a kind of haphazard, almost mocking, comical kind of prayer, but it gradually got more serious. And it was when I got sick that I needed a form for the faith, the inchoate faith that I was already feeling. So I went to church, and that's never really worked out for me very well, church, but it was the first step towards finding a form for faith.

On the difference between answers and faith

I think you can believe in God and not have faith. I think faith means living toward God in some way, and it's what you do in your life and how you live it. I don't feel the sense of mystery or terror alleviated by faith. I don't feel that at all. I don't understand when people present God as an answer to the predicament of existence. That's not the way I experience it at all. I have this hunger in me that is endless, and I think everyone probably has it. Maybe they find different ways of dealing with it, whether it's booze or excessive exercise or excessive art or whatever. I tried to answer it with poetry for years and hit a wall with that. And finally ... I discovered ... the only solution to me was to live toward God without an answer.

On how his illness has affected his wife

I think that the experience that I've gone through has been something we've both gone through and is very much changed our sense of our relationship of God and what love means. I feel some guilt, I suppose everyone does, because her whole life for the last 20 years has been defined in some ways by this illness. Even when it's not weighing on us, it's sort of always there. Every decision we've had to make we've had to plan for the fact if I couldn't be here. And it just always determines everything. I am very aware of that and the faith that we have forged out of that is very much shared.

Sam Briger and Susan Nyakundi produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.