“Follow the dotted line,” Lou Reed grumbled at me in 2004. “Look, put all the songs together and it’s certainly an autobiography – just not necessarily mine. I write about other people, tell stories, always did. Any truly creative person could make five albums a year, easily. Each record is just what you did that week. Another week you might have done the same songs differently. But listen – I love every last one of them. Every single second of every last one, okay?”

Okay. Fortunately for him, and for us, in late 1972 what he did that week beat most people’s year. Transformer remains a remarkable arranged marriage of gritty, witty words and pop succour. It anointed him the godfather of anti-stars, opening up a career that may otherwise have swiftly gone the way of all flesh.

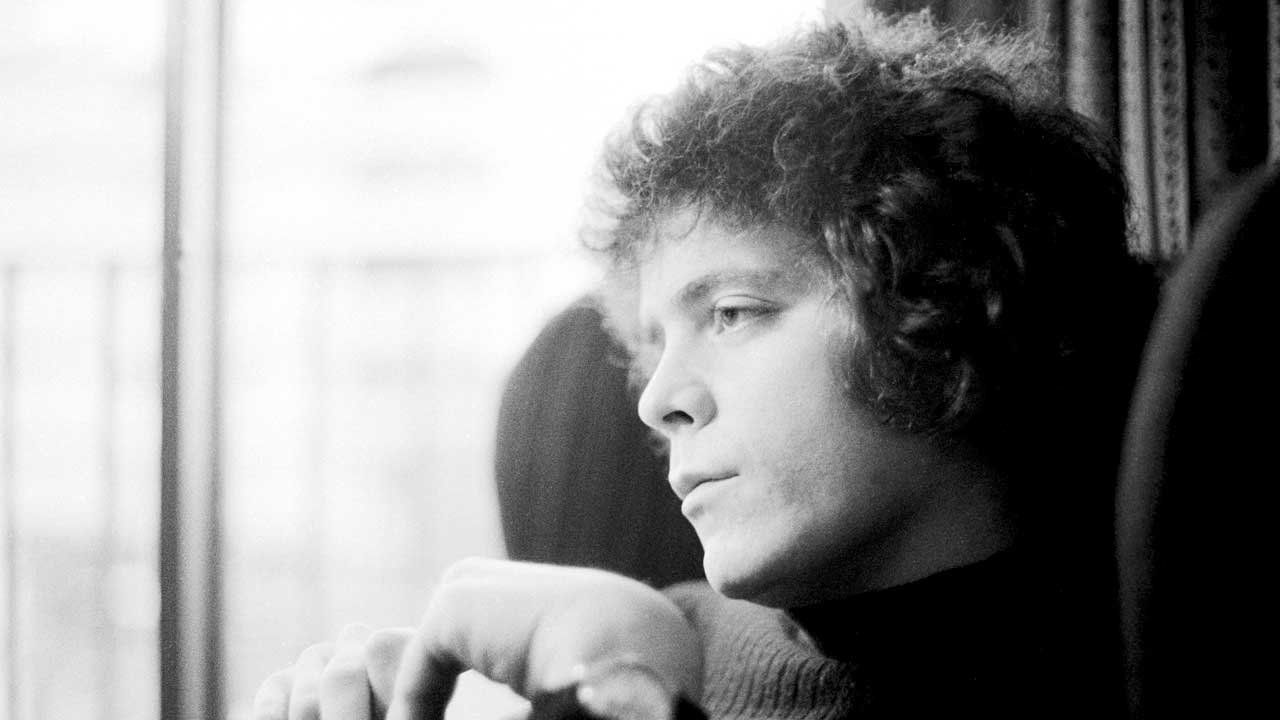

“I don’t have a personality of my own,” Reed said in 1972. “I just pick up on other people’s.”

He’d come to London for a change of pace, to “get out of the New York thing”, but his first, eponymous, post-Velvets solo album, recorded on the dirty boulevards of Willesden Green in West London, had stuttered rather than strutted. Nobody, least of all him, was sure where a former Velvet Underground frontman should go next.

This is where the personality came in, and plenty came out. Just five months after that debut, the November release of Transformer made Reed a household name in all the most disreputable homes. The world’s fastest-rising rock star, David Bowie, and his gifted lieutenant Mick Ronson, bang in the throes of Ziggy Stardust, coloured in Reed’s persona.

They coaxed forth the nervy, needy spirit of Andy Warhol that Reed had ingested and brought him alabaster-faced into the glam rock era. They gave his unorthodox songwriting and unique vocal stylings the chance to step out of the gutter and into the spotlight. The cult of Lou became a small religion as a freak hit single boosted his ego and confidence. A mixed blessing. Transformer remains a caustic, camp classic of palatable pop transgression.

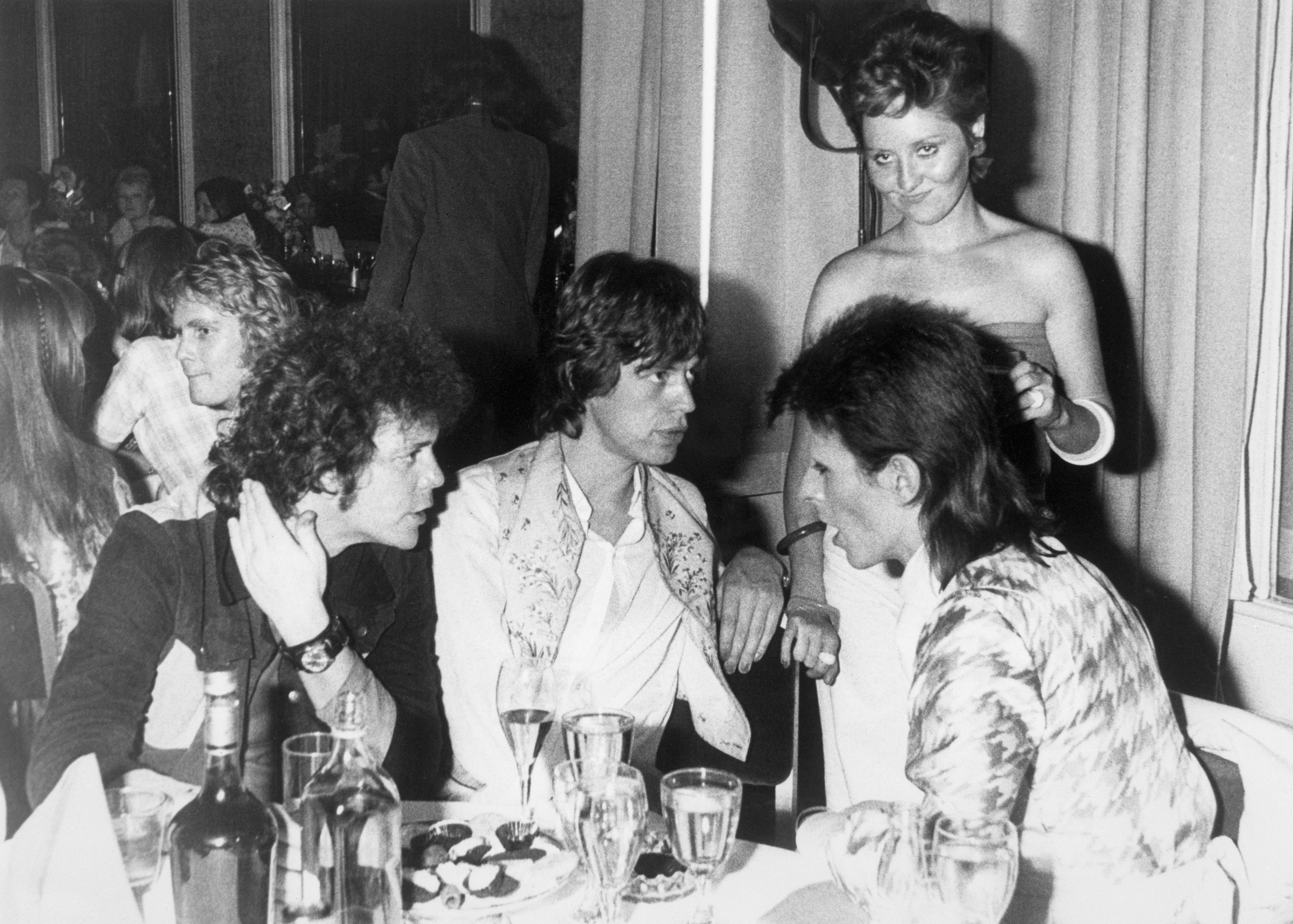

Things moved quickly. As a fan, Bowie had been name-checking the Velvets at every opportunity, playing their songs in his set for two years and even singing Andy Warhol on Hunky Dory. Perhaps calculating that he’d gain as much reflected cool as he’d give out, he whisked his American heroes and new pals – Reed and Iggy Pop – around London, showing them off to the press. Bowie saw in Iggy the wild, feral creature he himself was too cerebral to be. Reed arguably combined the essences of both, yet he was malleable. He wanted a career.

He knew the ‘business people’ were urging him to record with Bowie as the results would prove both vibrant and commercially viable. “And it turned out to be true, didn’t it?” he smirked.

Having always worn head-to-toe black, and accustomed to having films projected onto him, he allowed Angie Bowie to dress him more exotically. Going heavy on the black eyeliner, he became the Phantom Of Rock. “I realised I could be anything I wanted,” he drawled.

On July 8 he made his London debut, as Bowie/Ziggy’s guest at a Save The Whales benefit at the Royal Festival Hall. A week later his solo gig sold out the King’s Cross Cinema, and he smiled as it sank in that the audience knew the words to his Velvets numbers.

That’s where Mick Rock shot the live photo that became the iconic album cover. Years on, Reed sniffed: “I did three or four shows like that, then went back to leather. I was just kidding around. I’m not into make-up.”

His new glam guru was, though. Bowie ushered him into Trident Studios in August. Sessions were rushed, as Bowie’s other commitments, with Ziggymania breaking big, were escalating. Reed was, of course, grumpy on occasion. The honeymoon of mutual adoration was fading. Yet chief arranger Ronson and unflappable engineer Ken Scott (who’d produced the Ziggy album) caught lightning in a bottle.

Bowie had encouraged Reed to reveal tales and mysteries from his Factory years, to talk about the characters, the bathos and drama. He was eager to hear about underground New York – an impossibly glamorous notion to early-70s Brits.

The album became a seedy but redemptive, self‑contained world, where the drive for love led individuals down wrong turns into impersonal sex and imperfect drugs. There was no better microcosm of this than in one of the most unexpected hit singles of its era. “Any song,” Nick Kent wrote in the NME, “that mentions oral sex, male prostitution, methedrine and valium, and still gets Radio One airplay, must be truly cool.”

Walk On The Wild Side is, along with Perfect Day, one of the songs for which the world at large will remember Reed, even if he fluctuated in later years between being grateful and deeming it a pain in the albatross. At the time of recording, it was just another song to his ears. His own preference for a single was the wiry rocker Hangin’ ’Round. “Which is why no one listens to me.”

As he’d recount during the 1978 shows at New York’s Bottom Line (documented on the Take No Prisoners live album), he’d been approached by theatrical entrepreneurs in ’71. They’d proposed the idea of adapting the 1956 Nelson Algren novel about vice and addiction, A Walk On The Wild Side.

“Are you kidding?” Reed protested, true to his contrary nature. “It’s about cripples in the ghetto. I’m the best-qualified person to set music to a book about cripples in the ghetto?”

He demurred, officially, yet borrowed the title and sketched out ideas. Nudged first by Warhol and then by Bowie, he redrafted, peopling this backdrop with the New York personalities he’d been transfixed by and “picked up on”: Candy Darling, Joe Dallesandro (Little Joe) and Joseph Campbell (the Sugar Plum Fairy) were members of Warhol’s pansexual ‘superstar’ parade. This coterie of actors, artists, transvestites, junkies and wannabes was both eulogised and mildly mocked by the song’s taunting, partly ironic title.

“If I retire now,” Reed said soon after its success, having evidently warmed to it, “Walk On The Wild Side is the one I’d want to be known by, my masterpiece. I found the secret with that song. That’s the one that’ll make them forget Heroin.”

In fact, his new teenage audience in Britain, buying it because Bowie endorsed it, had never heard of Heroin, and at that time barely registered the Velvets. Transformer served as a gateway drug. With radio DJs too naïve or dense to notice the sex and drugs references, the single climbed to No.10 in the UK – albeit six months later – and broke in America.

Herbie Flowers’s upright bass slide, baritone sax from Ronnie Ross (Bowie’s sax teacher) and the ‘coloured girls’ going ‘doo, da-doo’ allowed Reed’s narration to drip with presence. He would pick the bones of New York for lyrical ideas ever more throughout a career of glorious highs and intriguing not-so-highs – not least on 1989’s New York – but this inked his identity.

Still in thrall to the bohemian preachings of mentor-guru-poet Delmore Schwartz, he would fret about “selling out”. Yet as his tones oozed and seeped from radios around the world, the rare blend of sarcasm and soul had the knock-on effect of boosting the profile of Warhol’s loosely related film trilogy Flesh, Heat and Trash. A debt repaid.

Warhol had also helped the genesis of Vicious, the album’s firm yet feathery opener. He’d suggested the title, adding, “You know, vicious, like: I hit you with a flower.” Ronson eases the riff along but goes for a flailing Moonage Daydream-style wig-out over the fade. To Lester Bangs, Reed declared it “a hate song”, adding: “I drink constantly.”

On an otherwise deftly produced album, Vicious is oddly tame and muddy, but we do get the first dose of the pop-operatic backing vocals from Bowie and female duo Thunderthighs, which became such a key feature of Transformer. The nursery rhymes from purgatory continue with Andy’s Chest – which Reed said was about Warhol’s shooting by Valerie Solanas, “even though the lyrics don’t sound like it”. He’d recorded it with the Velvets in 1969, but the Brits pulled back the tempo and highlighted the macabre imagery – bats, rattlesnakes, bloodsuckers.

The new verse about Daisy May’s bellybutton becoming her mouth was one step above music hall, and Reed confessed that he didn’t know what it meant. ‘Swoop, swoop! Rock, rock!’ went those multitracked backing vocals, as Bowie and Scott enacted their current obsession with a kind of postmodern doo-wop.

It’s easy to forget now that Perfect Day was ‘just’ the hit’s B-side (technically the single was a double A-side). Its surreal 90s crossover success as a family-favourite BBC commercial featuring Boyzone and Pavarotti meant that “twenty-five years on, it became even bigger than Wild Side ever was”, chuckled Reed. “Go figure.”

Back in 1972, it was already confusing and confounding people. Was this a beautiful, sincere love ballad or a subversive hymn to smack? If the former, its tenderness – ‘drink sangria in the park, feed animals in the zoo’ – felt authentic, topped by the Supremes-referencing ‘you keep me hanging on’. Others insisted it was a dedication to Bettye Kronstadt, whom Reed – for all this album’s overt sexual ambiguity – married in ’73. Either way, Ronson’s strings and piano capture the grandeur and frailty of falling in love. Even Reed was full of wonder for them. Cast against type here, he was someone else, someone good. “I’m really very inconsistent,” he muttered.

He’s on more familiar ground in Hangin’ ’Round, its prickly put-downs laid down not long after Bowie and Ronson had bashed out Chuck Berry’s Round And Round. Make Up is fairly difficult to misinterpret: ‘We’re coming out, out of our closets’ was a slogan the Gay Liberation movement had adopted as a global rallying call. This tough guy’s paean to lip gloss and perfume is enhanced by Herbie Flowers’s tuba obbligato.

Wagon Wheel and I’m So Free are conventional guitar chuggers that coast happily on the goodwill generated by the album around them: you can sense Ronson and Bowie trying a few minor twists to jazz them up.

Satellite Of Love, however, is another message from the gods. The piano-driven arrangement, with finger-clicks and those backing vocals, echoes Drive-In Saturday. Bowie soars stratospherically over the coda. Ken Scott has revealed that they could have made this climax even more huge with what Bowie sang on mic, but the star insisted that this album had better be about Lou, not him. Reed acknowledged the majesty of this section.

“It’s not the kind of part I could ever have come up with, even if you’d left me alone with a computer programme for a year. But David hears those parts, plus he’s got a freaky voice and can go that high. It’s very, very beautiful.”

The song in itself is no slouch, its sweetness turning sour through jealousy and paranoia. It had been demoed by the Velvets during the Loaded sessions, but nothing like this. The narrator’s comatose wonderment at technology – ‘I like to watch things on TV’ – seemed to hint at Warhol’s I-am-a-machine passivity then, but seems spookily prescient now. Addiction in another form.

New York Telephone Conversation is a gossipy send-up of Warhol’s diaries, while the old-time jazz of Goodnight Ladies is the antithesis, except for the cynicism, of the Velvets. Reed was imagining his interior life as a nocturnal, nightmarish cabaret. Indeed, on his next masterpiece, Berlin, he forsake these producers’ pop arrangements that dressed his vignettes of sickly city life and gambled on what Bob Ezrin called “a film for the ears”. Perhaps he resented the kudos afforded his collaborators here. “He’s very clever,” he snarled of Bowie. “He learned how to be hip. Associating his name with me brought his name to a lot more people.”

Mercurial as ever, he later asserted, “I love him. He’s very good in the studio. The kid’s got everything. Everything.”

Lou Reed changed his mind about Transformer, the album that made him a big noise and rebooted that autobiography, more times than he changed shirts. On its 25th-anniversary reissue in 1997, he commissioned me to write sleevenotes, only to nix them because, in a fit of revisionism, he didn’t want any mention, however passing, of “sexual experimentation”. Seven years later he told me he was thinking of remixing it. “That oughta be fun. We could put Bowie’s saxophone right at the back. We could mess around a whole lot.”

Such mischief. Today, it’s safe to say most of us haven’t changed our minds: it’s a louche, landmark album that changed – transformed, as in increased the voltage of – his life, and countless others.

Transformer by Lou Reed And Mick Rock, the limited edition book, is available from Genesis Publications.