A tramper who fell 16m from a Department of Conservation swing bridge was a victim of mismanagement, a former ranger claims

A senior DoC ranger who threw in his job over lax safety standards says the department is playing down the seriousness of an accident in which a tramper fell from a West Coast swing bridge after slipping through inadequate safety netting.

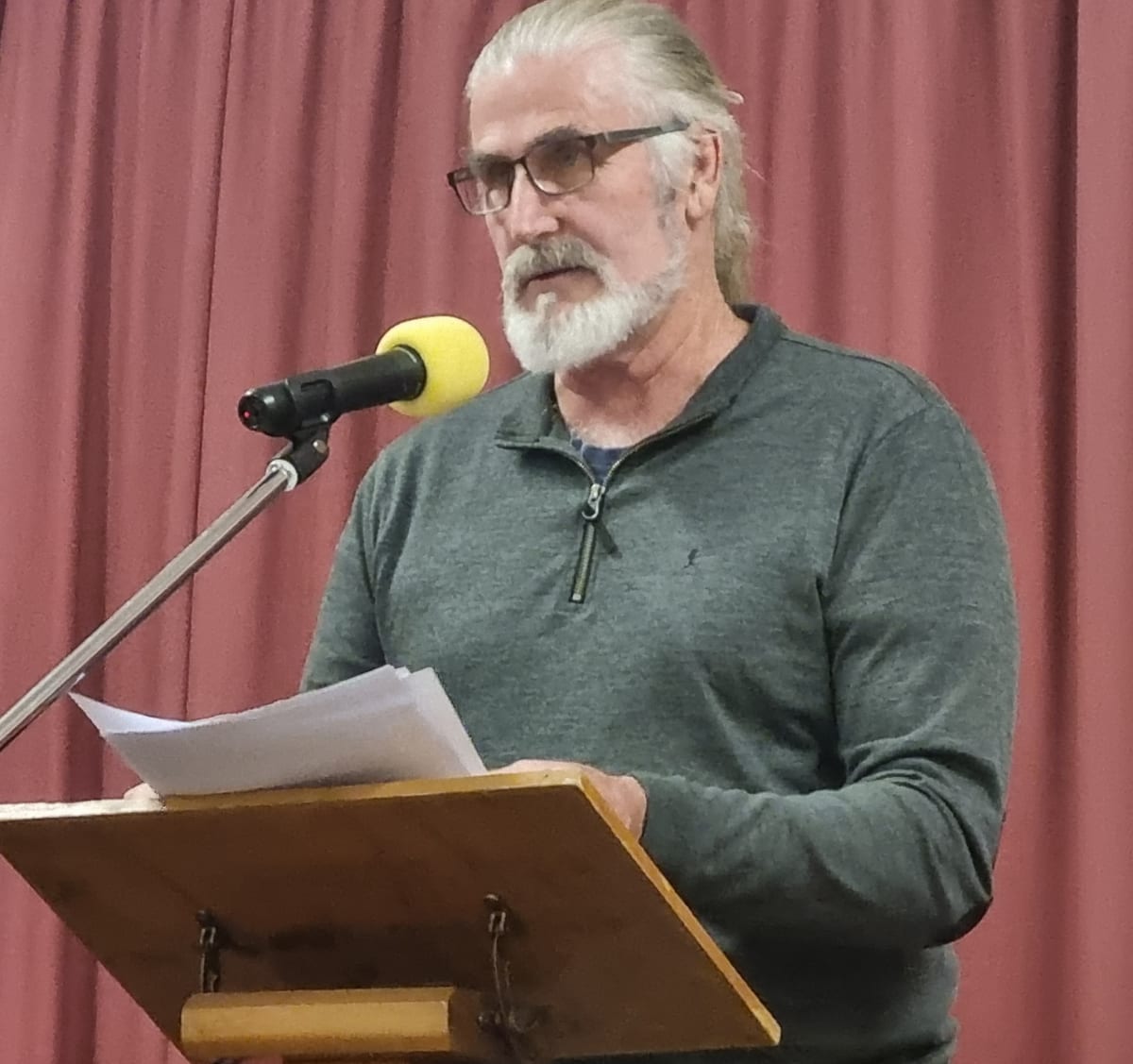

Dave Hawes, who worked for the Conservation Department on the Coast for 14 years, says he was so worried by escalating risks that he wrote to DoC director general Penny Nelson last year urging her to investigate.

“We have a structural management problem that has taken us back to Cave Creek levels of disconnect and resulting risk to public and staff … your health and safety team are completely disconnected from front-line reality,” Hawes wrote.

The Cave Creek disaster involved the collapse of a DoC West Coast viewing platform in which 14 people died.

The accident on the Collier Gorge swing bridge south of Hokitika illustrates his concerns, says Hawes, and there have been other potentially fatal incidents that he says reflect a lack of field skills and experience within DoC.

In a report released to media this week DoC reviews the June 2020 accident in which a Christchurch tramper was left hanging from the bridge by his pack before plunging into the Whitcombe River narrowly missing large rocks.

The man’s feet slipped sideways and he fell between the deck of the bridge and polythene barrier netting that had detached from its fastenings, the report says.

“The tramper’s pack snagged on the bridge holding their fall, but they could not regain the bridge deck and slipped out of the pack and fell 16m landing between rocks in water deep enough to cushion their fall.”

The man was swept down the river and managed to clamber out suffering only cuts and bruises.

Christchurch Tramping Club captain Bryce Williamson says the man was experienced at crossing swing bridges including the three wire type that have no barrier netting.

“He was reasonably staunch about it - he went on to finish the tramp after a change of clothes.

“But he was pretty shaken and a bit traumatised. He was left dangling by his pack straps over the drop and the rocks.

“He had enough time to try for the right spot but I’d say nine out of 10 times someone in that situation would have died.”

The group leader had tried to pull the man up but could not and rightly kept the others off the weight-restricted bridge, Williamson says.

“The last thing they needed was for the bridge to collapse and take others with it. The only way out for him was to drop into the river.”

Hopelessly underresourced

Williamson is reluctant to fault DoC for the close call saying only that the bridge was clearly not in an “appropriate” condition and the department is hopelessly underresourced.

Hawes has no such reservations.

“There were so many fail points here. They were using trawler netting and they were attaching it to the bridge deck and the first wire with steel loop ties.

“You have a moving structure and that’s never going to hold - the netting breaks away and DoC knew that.”

That’s borne out in an earlier report that says: “Nylon mesh wears through at these sites and may be not the best type to use, especially when we’re using it to prevent falls.”

And DoC staff who inspected Collier Gorge bridge three months before the accident found the netting detached in places, the report says.

That alone should have triggered a rethink, Hawes says.

“So what do they do? They fasten it back in exactly the same way. It’s like Einstein’s definition of insanity.

“There’s a serious competence and skill-set issue right there. An experienced person would have thought, hang on, this isn’t working, how do we make it safe?”

The workers had also cut the netting in two lengthwise, leaving it weaker on the cut edge and compounding the risk, Hawes says.

“There was trawler netting on bridges in my patch when I was leading ranger teams, but it was wrapped right under the deck and up the other side.

“It wasn’t in two pieces.”

Rolling out replacements

After the accident DoC ordered the gradual replacement of the polyethylene netting with steel mesh.

Heritage and visitors director Cat Wilson says at the time of the mishap 116 of DoC’s old-style swing bridges had barrier netting, but there was no specific policy on installing it.

Work on replacing the netting has been prioritised according to risk and is almost complete, she says.

“Remediation work on two remaining bridges has been planned; these bridges are temporarily closed and/or are regarded as low-risk through consultation with DoC engineers.”

Two investigations followed the Collier Gorge accident, one involving the team who worked on the bridge and one by a DoC engineering manager.

And an online system was set up for reporting visitor accidents.

Hawes doesn’t think that’s enough.

“They pretty much swept this under the carpet — it should have sparked a full ICAM [incident cause analysis method] inquiry that would have revealed deficiencies in staff training and experience and the failures of management to ensure those things were in place.”

What keeps the former ranger awake at night, though, are more recent incidents than Collier Gorge.

“Because they’ve lost so many staff and the budgets are slashed to hell, they have to prioritise high-risk stuff like this.

“But that means they’re not doing the basics any more like track clearing and in doing that they’ve created a whole new risk to the public.”

Another near miss

Hawes is thinking about a mother and children who lost their way on an overgrown track in the Robinson Valley a couple of years ago trying to find the Lake Christabel hut.

“The track was overgrown and had completely disappeared at one point and it was getting on dark.

“They were bushed and had to spend the night in the open.

“They were just lucky the weather was fine. It could have ended badly.”

In the past when DoC had the budget for it the track would have been regularly inspected and put on the work programme before it became dangerously overgrown, he says.

The near miss that sticks in his mind – and the one that led to his quitting in January this year – involved an untrained DoC worker flouting operating rules by trying to fell a large tree on a track using a digger.

“He told the young guy he was working with to climb on the suspended trunk and hack through the root ball. He broke every bloody safety rule in the book.

“Fortunately the young bloke refused and videoed it on his phone.”

Hawes says in another incident a worker new to the job started unloading equipment from the rear of a helicopter close to a hut while the tail rotor was still spinning.

“His supervisor was supposed to be there but wasn’t.

“If he’d hit the rotor the machine could have spun and killed him and the pilot and the people on the hut veranda.

“The chopper pilot nearly lost it, and I don’t blame him, but he got hauled over the coals.

“It was butt-covering by DoC management and it was about a lack of experience and supervision.”

Hawes quit two years earlier than he intended worn down, he says, by the stress of trying to keep visitors safe and assets in good shape without the necessary resources.

“You look at something like the Collier Gorge accident and it’s like all the holes in the Swiss cheese slices are lining up again.

“I don’t want to be around to see people killed.”

Made with the support of the Public Interest Journalism Fund