A year ago, Jeff Cohen and three others survived a hostage standoff at their Reform Jewish synagogue in this Fort Worth suburb.

Their trauma did not disappear, though, with the FBI’s killing of the pistol-wielding captor, 44-year-old British national Malik Faisal Akram.

Healing from the Jan. 15, 2022, ordeal remains an ongoing process.

“Let’s be blunt: We’re healing. We’re not healed,” said Cohen, 58, a Lockheed Martin engineer who serves as president of Congregation Beth Israel and its 140-family membership.

The 10-hour standoff ended about 9 p.m. that Saturday as the remaining hostages — including Cohen — escaped and the FBI’s tactical team gunned down Akram.

The violence left the synagogue with broken doors and windows, shattered glass and bullet holes. Within three months, repairs had been made and the congregation returned. But one year later, deep wounds still fester.

“We have a lot of people who are still feeling it bad,” Cohen said as two fellow hostages, Lawrence Schwartz and Shane Woodward, nodded affirmatively in a group interview at the synagogue. “We have parents who aren’t very comfortable bringing their kids to Sunday school.

“We’re forever changed,” he added. “We’ve had to get used to having security here all the time.”

The recent upsurge in antisemitic rhetoric and actions nationally has intensified both the congregation’s traumatic feelings and its resolve to move forward without fear, said Anna Salton Eisen, a founder of the synagogue and author of books about her parents surviving the Holocaust.

“After the hostage crisis, I’m inspired to go out and try to use this, along with the Holocaust, as an inspiration to fight hate,” Eisen said.

It all started with a knock at the door. On a cold, windy Saturday, a man who appeared homeless showed up outside Beth Israel.

The stranger immediately unsettled Schwartz, who was helping Rabbi Charlie Cytron-Walker prepare for the morning Shabbat service.

“I said, 'I don’t like this,'” recalled the retired accountant, 87, who helped lead security for his previous synagogue. “I said, ‘Charlie, don’t open the door.’ He went ahead and opened it.”

The temperature hovered near freezing and the wind made it feel even colder. Cytron-Walker showed the stranger compassion — as his Jewish faith calls him to do — and invited Akram inside. They chatted and the rabbi made him tea.

Akram had spent time in Dallas-area homeless shelters, but the cold wasn’t why he wanted to come in the synagogue.

“I had no indication that he was intending to do us harm until I heard the click of a gun, which was an hour after I met him,” said Cytron-Walker, 47, who had served at Beth Israel for 16 years.

That click came at about 11 a.m. as Cytron-Walker prayed facing the front of the sanctuary.

The weather and the COVID-19 pandemic made for a light in-person crowd that day. While an unknown number watched online, just three besides the rabbi came in person: Cohen, Schwartz and Woodward, who arrived a few minutes late.

Woodward, 47, listened to the first part of the service via Zoom on his drive. He heard Cytron-Walker mention the guest.

After taking a seat, Woodward noticed Akram.

“I did hear a lot of fidgeting going on. He was kind of rustling around back there,” said Woodward, who works for PepsiCo. “I waved to him, and he was very polite. He waved back. He smiled, nodded. … We were in the middle of praying when it happened.”

During the standoff, Akram demanded the release of a Pakistani woman serving a lengthy prison sentence in Fort Worth after being convicted of trying to kill U.S. troops.

The hostages said Akram cited antisemitic stereotypes, believing that Jews wield the kind of power that could get the woman released.

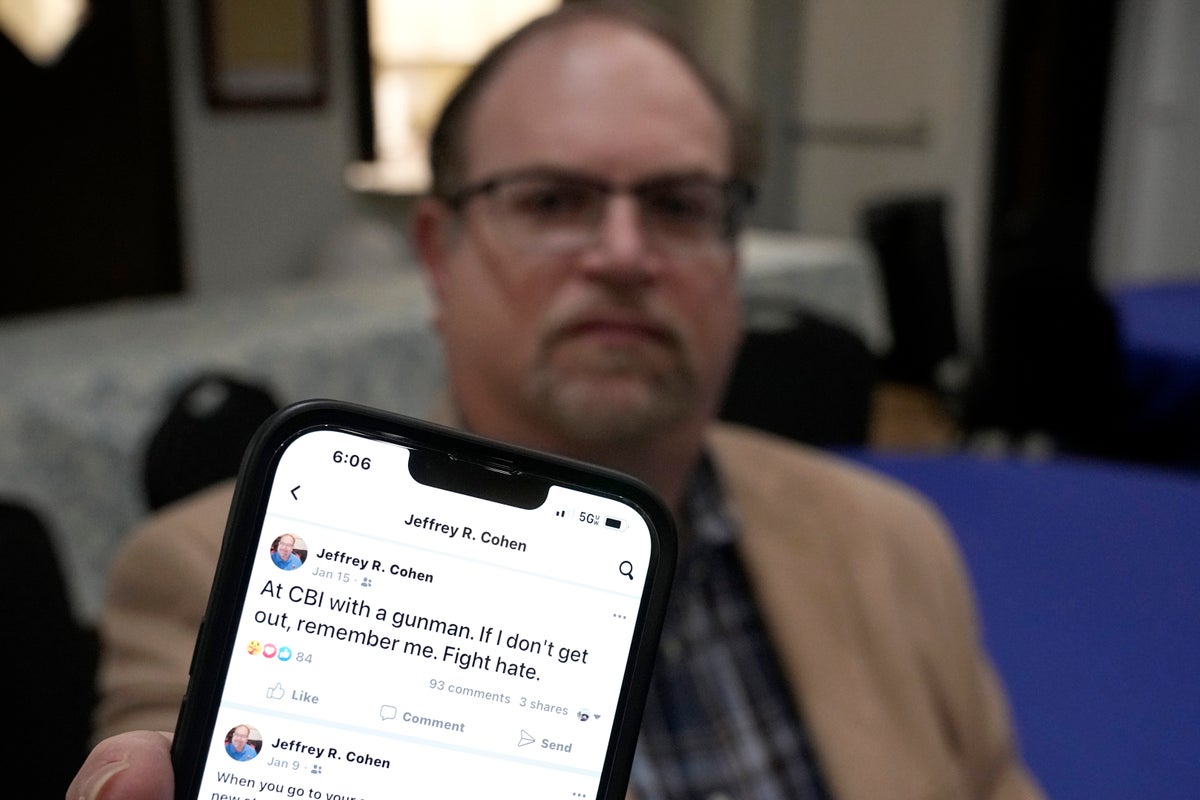

“At CBI with a gunman,” Cohen posted on Facebook. “If I don’t get out, remember me. Fight hate.”

Schwartz apparently reminded Akram of his father, and the gunman started calling him “Dad.” At one point, he got his captor’s permission to use the restroom.

“He said, ‘I’ll let you go, but if you don’t come back, I’m going to kill these three guys,’” Schwartz recalled.

About six hours into the standoff, his fellow hostages told Schwartz, who has hearing problems, to leave. He didn’t understand at first. But they had talked Akram into releasing him.

Initially, Schwartz was upset. He didn’t want to leave them behind, but later realized they stood a better chance without him.

“I’m not able to move very fast,” Schwartz said. “They could run. But not me.”

Woodward grew up Baptist but was in the process of converting to Judaism. As the standoff dragged on, he remarked, “Rabbi, I’m still converting.”

“There is no guarantee that we were getting out of there, and this is what was going through his mind,” Cytron-Walker said with a chuckle. “Jeff turned around and said, ‘What?’ Since we all got out, it’s really one of the humorous moments.”

Hours later, Akram was becoming more agitated.

The hostages’ fears that he would shoot them increased.

“He was yelling at the negotiator, and when he hung up, he got really calm,” Cytron-Walker said. “He turned to us, and I thought that we were going to die. He asked us for some juice.”

After Cytron-Walker walked to the kitchen, Akram decided he wanted a soda instead. The rabbi returned with a can of soda and a plastic cup.

That’s when the chance to escape came.

“He was holding on to the liquid with one hand,” Cytron-Walker said. “For the first time all day, he did not have his hand on the trigger.”

The rabbi yelled “Run!” and threw a chair at Akram. They escaped through a side door.

Simultaneously and unknown to the hostages, the FBI team entered the building to attempt a rescue. Like the rabbi, the authorities were concerned about Akram’s state of mind.

The hostages say Akram attempted to shoot at them as they ran but his pistol misfired.

“I know God was with us,” Woodward said.

Before the standoff, Cytron-Walker had already interviewed for a new job as rabbi at Temple Emanuel in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The hostage crisis delayed that process, but he started his new job in July.

Even 1,100 miles away, “the events of Jan. 15 continue to impact almost every aspect of my life,” he said.

From his sermon topics to his speaking engagements on antisemitism to his recent opportunity to light the menorah at the White House’s Hanukkah reception, the hostage crisis figures heavily, Cytron-Walker said.

“I’m not having nightmares or anything that would resemble PTSD,” he said. “I never know if that could come up at some point in time, but I’m very thankful that it hasn’t as of yet.”

A year later, the hostages urge other houses of worship to take security training seriously. Cytron-Walker credits it with getting out safely.

But next time, Schwartz said, he would act on his concern and call 911.

“I don’t care if the congregation wants to throw me out. I don’t care if the rabbi never wants to talk to me again,” said Schwartz, who now wears a custom-made yarmulke with the message “Stronger Than Hate” on the back. “I should have operated on my thoughts, and I didn’t.”

But Cytron-Walker said he does not regret abiding by his faith.

“He looked like he was a homeless man, and I continue to live with the fact that I was fooled,” he said. “We have to be able to live our values even when they’re hard.”