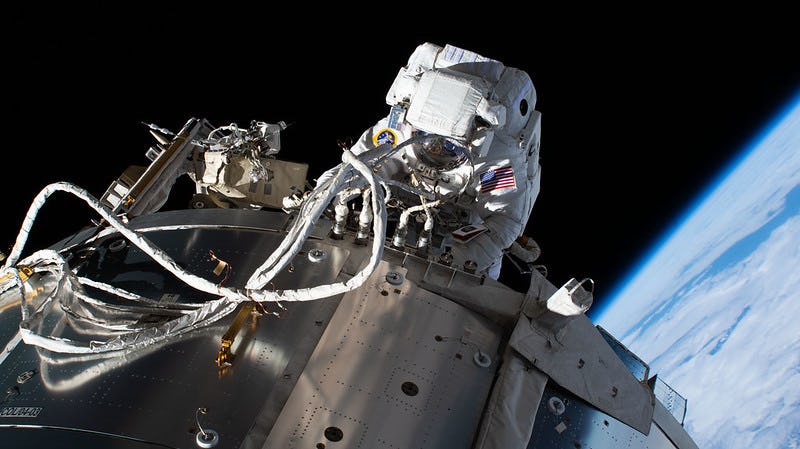

To become an astronaut, a person must already possess an arsenal of grit. After all, if there’s a misstep during a spacewalk, a difficult assignment (like controlling the space station’s large robotic arm), or, perhaps, an unplanned half-year-long extension of an orbital assignment — like what Starliner’s crew experienced this summer — an astronaut must adapt. Still, outer space can push even the most mentally tough person’s limits.

That’s where Anna Morgenthaler, an operational psychologist who works at NASA in its behavioral health and performance group, comes in. An operational psychologist is one who works with professionals in high-risk positions, including those who live and work on the International Space Station (ISS).

Inverse spoke with Morgenthaler to better understand how astronauts work on and maintain their mental health, both on Earth and while they are in space.

Astronauts acknowledge and tackle perfectionism head on

People who succeed in NASA’s astronaut program work well in groups and they also possess self-awareness, including the ability to be introspective and to understand their own strengths and weaknesses, and how those might affect others. They must also provide and receive feedback without getting defensive.

Being successful at this means avoiding perfectionism.

“We know that perfectionism can get in the way of performance. That it can cause so much anxiety, that we can get in our own way,” Morgenthaler says. “The perfectionist mindset that some of the high performers we have can trend toward — like if I don’t do it right, then I failed — we want to shift to a learning mindset.”

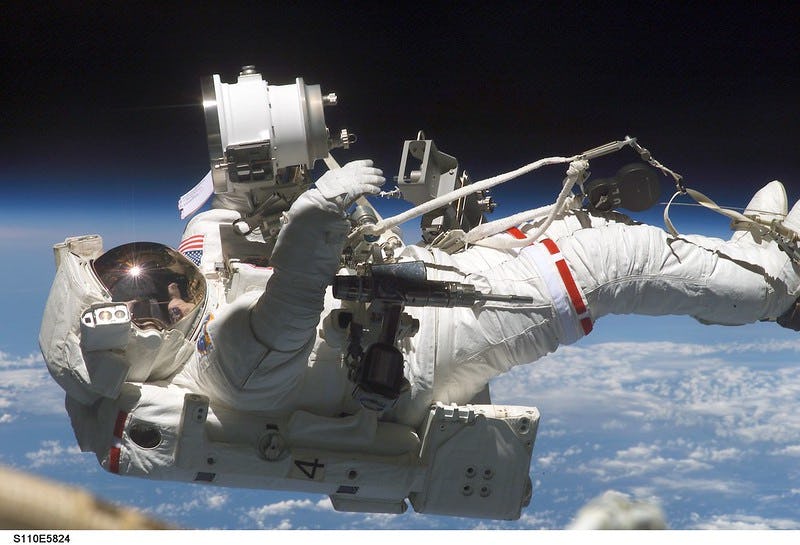

Morgenthaler calls this cognitive flexibility. Adapting to new environments, perspectives, and the demands of a months-long mission are critical to excel in the spacefaring marathon. For instance, if an astronaut is on a spacewalk and something doesn’t go as planned, a learning, rather than perfectionist, mindset will help them adapt quickly and come up with new solutions.

Psychologists, including Morgenthaler, will encourage astronauts to adapt quickly, and to prioritize a quick decision, while breath work (more on this below) could be a solution to temporarily compartmentalize emotions and set aside the mistake to get the word done and return to safety if necessary.

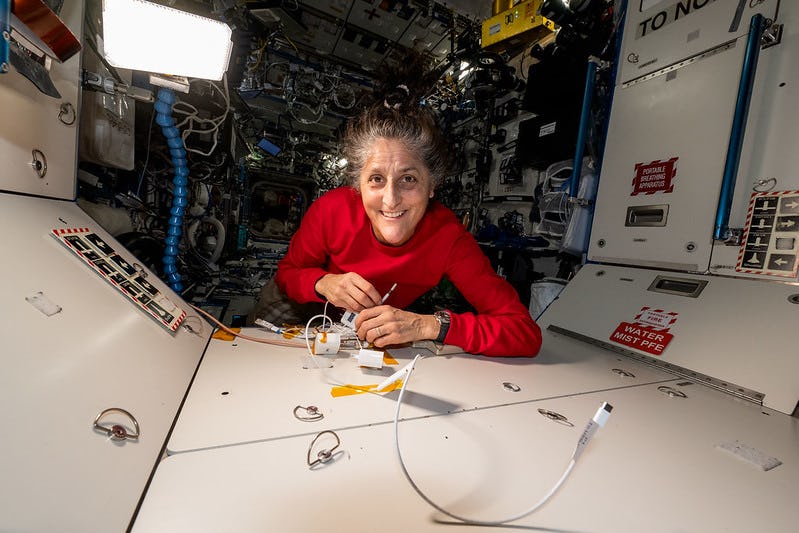

If you are on the ISS, you are going to therapy

Astronauts commit to a mental health schedule. This is part of the way they balance work with personal time and rest.

“Our private psychological conferences are scheduled on their timeline every two weeks,” Morgenthaler says. “That's a required medical standard, so that is every two weeks without fail.”

They can choose to have more time with a psychologist, too, if they request it.

Even in closely-packed quarters, astronauts carve out private space for these video calls. The phone-booth sized sleeping compartments are one place for their sessions. If they have to get creative, say if there’s many crew members onboard the ISS at one time, an astronaut has headphones and their own iPads to keep the conversation private.

Talk therapy allows astronauts the space and time to work through any issues, including perfectionism tendencies, on a regular basis. This way, nothing that could affect their mental health or ability to do their jobs gets left simmering or on the backburner.

Breathing techniques are key

Astronauts lean on breathing techniques when they need to manage their feelings in the middle of high-stress situations.

Breathing techniques help astronauts set aside nervousness and fear that they’ll make a mistake so that they can get the work done that needs to be done or to solve an issue, Morgenthaler says.

One approach is squared breathing. Here, someone breathes in for four counts, holds for four counts, breathes out for four counts, then holds for four counts, and repeats.

“Anytime you're regulating your breath, you're also regulating your heart rate. It helps calm your whole body down,” she says. Studies on various controlled breathing techniques from squared breathing to diaphragmatic breathing back this up. Research suggests that this form of breathing helps to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which is in charge of helping the body to relax.

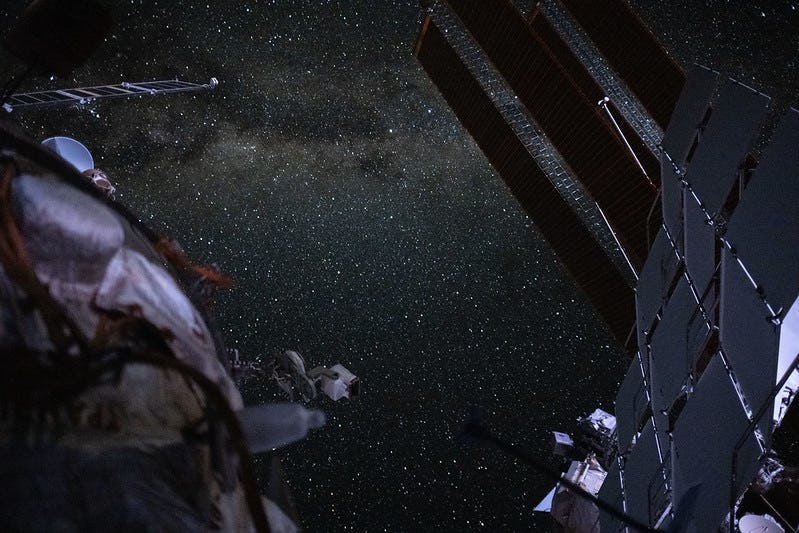

While she’s never been to space, Morgenthaler imagines these breathing techniques would be helpful when an astronaut is so far from home, in the void of space, and having to accomplish a difficult task.

Space is transformative, physically and emotionally. Mental health care not only allows astronauts to endure their long missions far from home, but also fosters a smoother transition back to Earth when their flight ends.