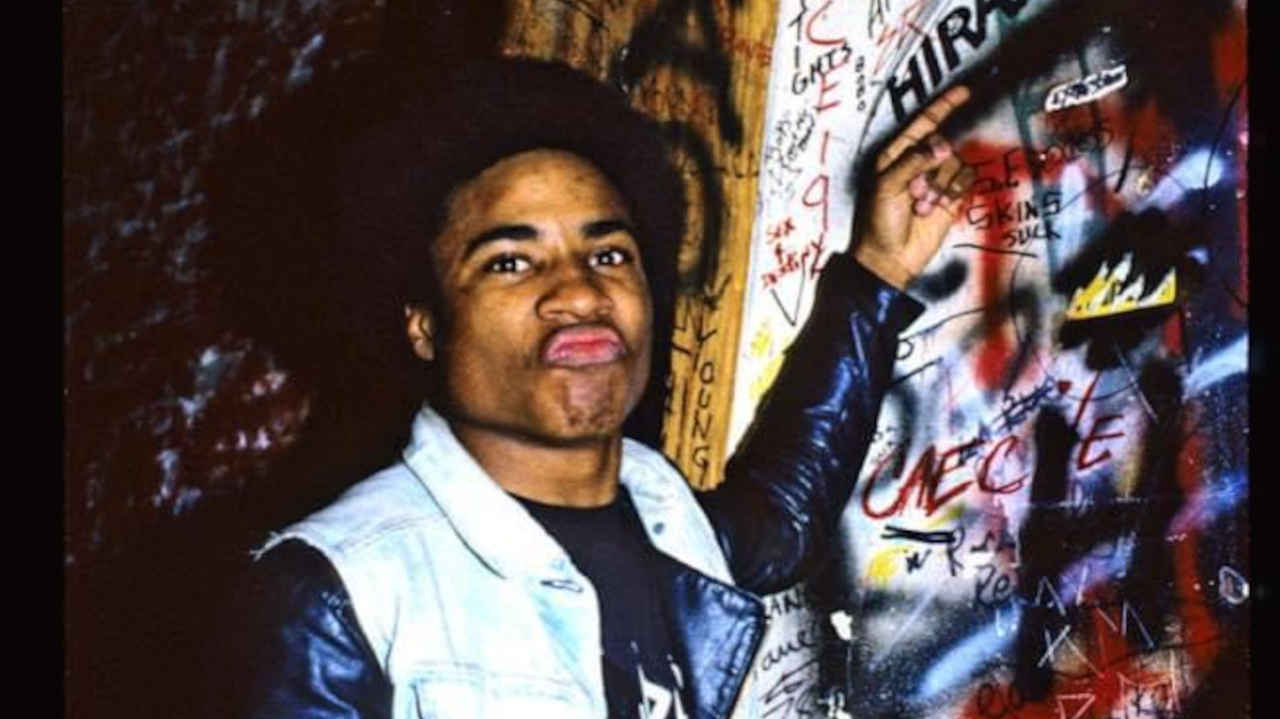

There’s a word that Hirax singer Katon W. De Pena uses a lot: integrity. “People aren’t stupid, they listen. They recognise integrity,” he says at one point during our conversation. “We were stubborn. Maybe that counted against us, but integrity was important,” he says at another. Then there’s the two word credo that define both Hirax and Katon himself: “Integrity matters.”

Integrity has carried Hirax a long way. The Los Angeles band might not be hugely well-known outside thrash circles, but they can legitimately lay claim to being one of the scene’s founding fathers. They were there at the very start of it all, mixing it up with Metallica and Slayer. They never came close to becoming as big as either of those bands, but the two albums they released during their original run – 1985’s Raging Violence and the following year’s Hate, Fear And Power – are cult classics beloved of collectors and connoisseurs.

They split in 1987, just as their peers were elbowing their way into the mainstream, a victim of ego clashes and stubbornness. But a second act, which started in the early 2000s and continues to this day, saw them returning to the fray, releasing a string of killer modern thrash albums.

Katon himself is a lifer in this business, which explains why he’s uncomplainingly sitting on the end of a Zoom call at 4am his time, the result of a scheduling snafu (ours, not his). This hasn’t dampened his full-blast enthusiasm for his band, for music and for life in general, which is contagious. His energy is doubtless helped by the fact that this one-time boozehound quit drinking a while ago.

“We partied with bands like Slayer and Exodus, but we’ve lost a lot of people over the years,” he says. “When I turned 60 [in 2023], I made a decision: would I like to be around another 10 or 20 years? The answer was yes.”

Katon was born on the East Coast, the son of a navy veteran who served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam. When he was a kid, his family moved to Buena Park in Orange County, south of LA. He’d grown up listening to blues, soul and R&B, but this was the 70s, and hard rock and heavy metal were on the rise. He went from listening to Otis Redding, Muddy Waters and Sam Cooke to Jimi Hendrix, Black Sabbath, Montrose, Ted Nugent, Judas Priest, AC/DC and Thin Lizzy.

“I had to learn about that music - it was almost like a survival skill, cos I was the only black kid in the area,” he says. “I learned how to make friends, but I loved the music too. And I was such a hyper kid, it was perfect for me.”

In 1982, inspired by the New Wave Of British Heavy Metal that was filtering through to the US, as well as homegrown heroes Twisted Sister and Riot, he put together his own band, Kaos. A lot of other kids his age had the same idea.

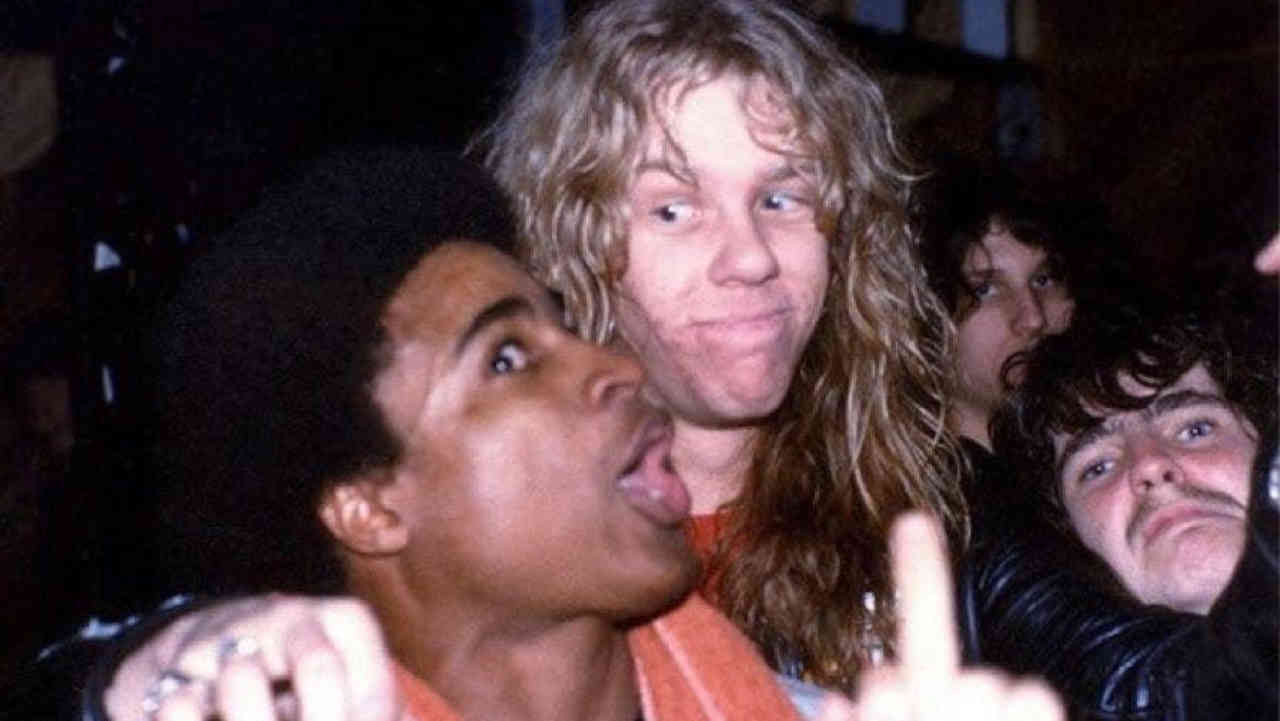

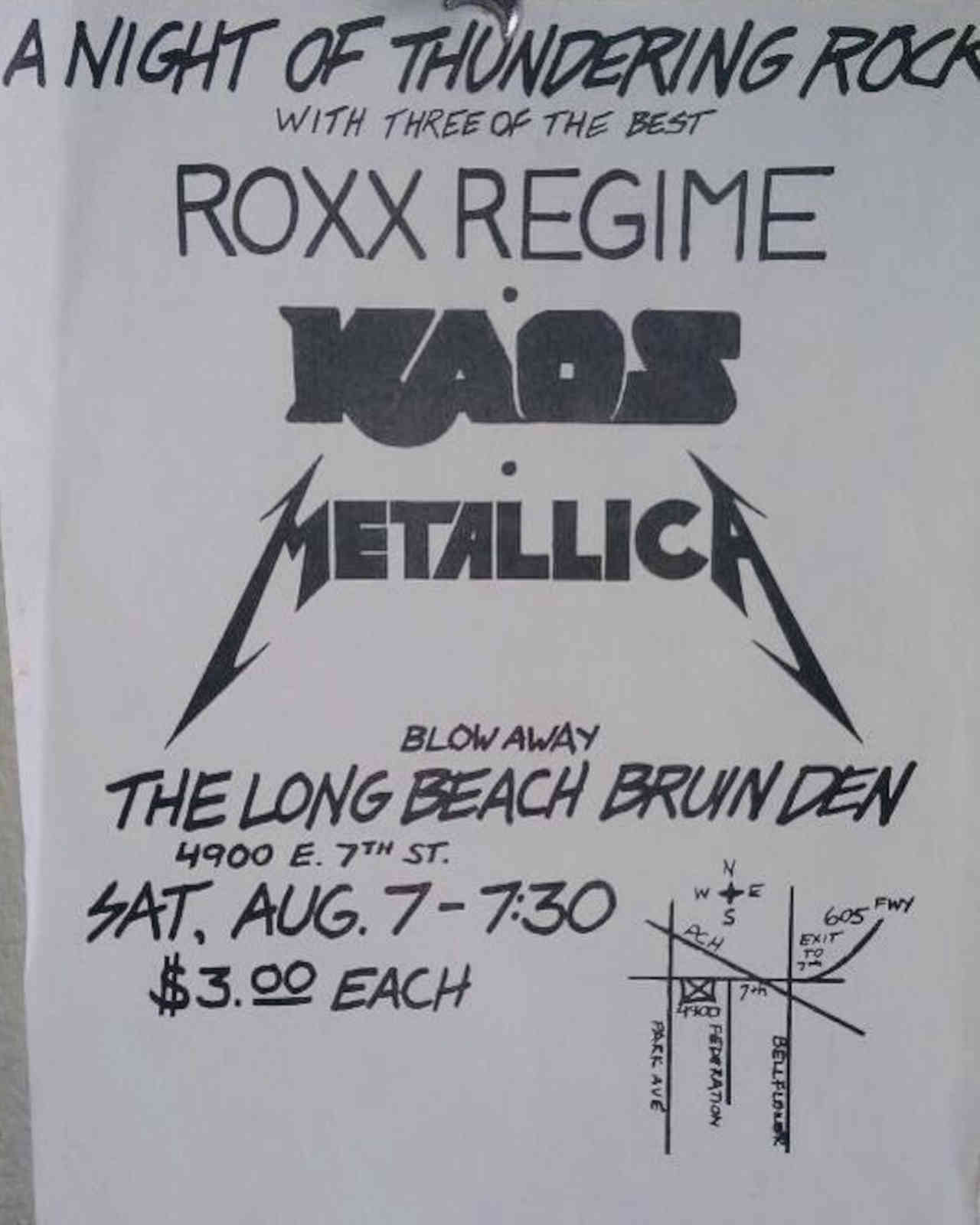

“I knew James Hetfield when he was still in Leather Charm. I saw that whole thing happening,” he says, referring to Metallica’s formation. “We played a show at the Bruin Den in Long Beach. It was Roxx Regime headlining, who became Stryper, then Kaos, then Metallica opening. They were only just starting to pick up their speed.”

It was an electrifying time. “Metallica was playing fast, Slayer was playing fast, we played fast. We were influencing each other. We all wanted to play faster than the other guy. It was a competitive thing. A lot of us didn’t like each other back in the day. Slayer were hard-ass. They didn’t even get along with Metallica.”

By early 1984, Kaos had become Hirax. They released a four-track demo that married the NWOBHM’s denim-clad power with thrash’s punk-adjacent attitude, with Katon’s primal yet operatic howl at the centre of it.

A natural born networker, he was already embedded in the tape-trading scene. Bands around the world would swap rehearsal and demo tapes via snail mail, boosting each other in the process. “The tape trading thing was at fever pitch,” he says. “It was the internet of the day.”

He reels off the people he corresponded with: “Anthrax, Overkill, Chuck Schuldiner when Death were still called Mantis, Tom G Warrior of Hellhammer, Kreator back when they were called Terror, [late Bathory mainman] Quorthon. We were turning everybody onto bands that wouldn’t have got noticed any other way.”

His own band’s demo was in circulation. “We’d send out 50 cassettes a week, no problem,” he says. “I remember one day I got a knock on the door, and there’s this big biker guy. I’m thinking, ‘What the hell’s going on?’ He says, ‘Are you Katon? I wanna buy two Hirax demo tapes.’ And he paid me three dollars each then got on his motorcycle and rode off. That’s when I knew something was happening.”

Big labels weren’t interested in this nascent scene – it was too raw, too underground, too uncommercial to warrant attention. But a bunch of metal-loving kids had started their own labels to get this music out there. One of these was Brian Slagel, who had founded Metal Blade records a couple of years earlier and given Metallica and Slayer their first breaks. “Brian was so important to that scene,” says Katon. “He was the only person in LA who took a chance on this kind of music.”

Slagel gave Hirax a spot on the sixth instalment of his Metal Massacre compilation in early 1985, and put out their debut album, Raging Violence later that same year. Featuring a logo designed by Celtic Frost’s Tom G Warrior and artwork by underground artist Pushead (later famous for his work with Metallica), it was raw, energetic and uncompromising.

But then Hirax themselves were uncompromising. Where other metal bands turned left, they turned right. “A lot of bands were ‘evil’ - Mercyful Fate, Slayer,” says Katon. “That wasn’t Hirax’s deal. I love that stuff, but there was so much of it, we didn’t want to do it. We wanted to bring everybody together - metal kids, punks, grindcore freaks.”

They were principled in their own way, too. In 1984, they turned down the chance to appear on Welcome To Venice, a compilation put together by Suicidal Tendencies. Suicidal were the hottest hardcore band on the west coast, but their shows were plagued by gang violence.

“We loved the band, but we didn’t like the gang stuff,” says Katon. “If we’d been on that record, it would have said that we were part of it. Not that we were scared of it, we just thought it was stupid. Why do you want people bringing weapons into a gig? Thrashing’s enough.” (One of their songs, Destruction And Terror, did appear on another compilation, Anglican Scrape Attic, a 1985 flexi-disc compilation put together by Digby Pearson, founder of groundbreaking UK label Earache).

This determination to do what they wanted and screw everyone else played into the integrity that Katon talks about. But sometimes that integrity spilled over into self-defeating stubbornness.

“We were the punks of the label,” says Katon. “We wouldn’t stand around having our photo taken. Back then, we thought you were a poser if you did that. Now I’m, like, ‘Come on, lighten up.’”

Unsurprisingly, Hirax were wary of the ‘business’ side of the music business. This extended to the band essentially managing themselves. “There was interest, but when you‘re a young metal guy with a punk attitude, you’re like, ‘I don’t need that shit,’” says Katon. “We didn’t like being pushed around. It was a control thing - we didn’t want to be like other bands. Now I know there’s nothing wrong with it, but back then we were young and stubborn.”

They weren’t stubborn enough to prevent themselves being pressured into returning to the studio to record a follow up to Raging Violence. Their second album, 1986‘s Hate, Fear And Power, was a ferocious 16-minute burst of fury that owed as much to the emerging crossover scene as it did thrash.

“We were being rushed by the label to get some new product out.” says Katon. “They were saying, ‘Look what Slayer’s doing, they’re working really hard, putting out EPs and albums.’ That‘s why that record’s so short - we didn’t have the material.”

Label pressures aside, things looked to be going well for Hirax. They were working with Black Flag’s booking agency – independent, naturally – and gigging up and down the west coast. But cracks were beginning to appear.

“When a band starts getting popular, egos change, myself included,” says Katon. “You think you’re doing more than this other guy, the other guy doesn’t think you’re doing enough.

The drinking - our drug was alcohol - didn’t help. And I got more frustrated because Hirax was my baby.”

By 1987, it had gotten too dispiriting. “I just left. They tried to go on without me, but I think what happened is that there are certain guys in every band who do a lot of the work, and that was always my thing.”

Without Katon, Hirax fell apart. Their timing was lousy. Thanks to Master Of Puppets and Reign In Blood, thrash had become a genuine commercial force. If they had stuck it out, who know what might have happened.

“I don’t kick myself, because if you do that, you’ll spend your whole life kicking yourself,” he says. “But we should have kept goin

Post-Hirax, the singer formed the short-lived Phantasm with his old friend and ex-Metallica bassist Ron McGovney, Dark Angel drummer Gene Hoglan and, briefly, Suicidal Tendencies guitarist Rocky George. “If you blinked, you missed it,” he says. Once again, his refusal to play the game was part of the problem. “I always wanted to be underground. We got a lot of offers, but none of them felt right. We should have gone with them.”

By 1988, Phantasm were finished. Katon wasn’t done with music, but he was waking up to the fact that maybe there was something to be said for not constantly pushing against the music industry. “I said, ‘I gotta stop being a dumbass and learn the business,’” he says.

The passion for music which saw him delving into the NWOBHM as a kid and becoming involved in tape trading when Hirax were taking off was undimmed, but rather than slog it out in another band, he got a job in a record store to see how things worked from the other side of the fence. That led to a job at major label BMG. “Yeah, that was ironic, given how I was before,” he says. One of the bands he dealt with were Tool, around the time of 1992’s Opiate EP and 1993’s Undertow album.

“I was there when they recorded Sober,” he says. “It was amazing seeing that whole thing take shape and grow.” Maynard James Keenan liked him because he was the most hardcore person in the BMG office. “He’d come over and go, ‘You like The Jesus Lizard?’ And I’d go, ‘Yeah, they’re one of my favourite bands.’”

By the late 90s, he’d started his own label, Junk Records, signing kick-ass punk-metal bands like Zeke and Electric Frankenstein. It was a hand-to mouth operation - he wanted to sign Turbonegro and Nashville Pussy but “didn’t have the money, and it wasn’t a lot, only $5000.”

People would occasionally come up to him and ask him if he was Katon from Hirax, but he didn’t miss his old band. There was no talk of reuniting. “Everyone had gotten married and had kids. I was the only one that was still involved in the music scene,” he says.

That changed when he met the woman who became his wife, Anne. Her band, X-It, were playing a club he was booking gigs for. “I thought she was really cool, but I was so nervous that I‘d never try anything. I didn’t want to freak her out,” he says, laughing. “One day she put her hand on my leg. I thought, ‘Well, I guess she likes me.’”

Anne was at Katon’s house when she found a box full of letters. It was old Hirax fanmail. “She started reading the letters: ‘Are you kidding, people really love your music.’” She burned Hirax’s albums onto CDs and put 5000 of them on a website. “She sold them all,” says Katon proudly.

It was enough to convince him to resurrect Hirax. They returned with 2000’s blazing El Diablo Negro EP, also featuring Raging Violence-era bassist Gary Monardo and drummer John Tabares, plus guitarist Greg Eickmier. That line-up didn’t last, but Hirax did. Since their return, they’ve released three albums (2004’s The New Age Of Terror, 2009’s El Rostro de la Muerte and 2014’s Immortal Legacy), plus a string of EPs and splits.

“I never thought what is happening with the band would be going on now,” he says. “I’m a lot more focussed than I was when I was in my 20s. I never thought I‘d be the guy sitting here saying that. I never thought I’d be alive this long.”

Even away from the band, Katon stays involved in music. He spent five years DJing at famed Sunset Strip hangout the Rainbow Bar & Grill. He and Anne launched the campaign to raise money for the statue of Lemmy that stands in the outdoor drinking area.

“It was just paying him back,” he says proudly. “Any thrash guy, we all owe Lemmy and Motörhead a debt. There were no rock stars involved in that. It was all donated by Motörhead fans around the world. You cannot piss Motörhead fans off.”

There’s a new Hirax album on the way. Titled Faster Than Death, it‘s set for released in November. Katon’s massively vibed up about it, not least because of the involvement of legendary producer Max Norman, famous for his work on Ozzy Osbourne’s first two solo albums. “And Y&T’s Black Tiger and Megadeth’s Countdown To Extinction,” he adds, ever the connoisseur. “We funded this album ourselves, which is why I thought he’d say no. He’s got major integrity to take on a band like Hirax.”

It’s that word again: integrity. Katon W. De Pena may have shaken off some of the stubbornness that got in the way first time around, but that core value remains.

“I want to do things my way – it’s my biggest problem and my biggest strength,” he says. “It’s not the perfect way to live - maybe I’d have more money than I do now if I hadn’t been so stubborn. But that’s not what it’s about. It’s about doing what you want to do and giving people that. Stay true to yourself and to your music. Integrity matters.”

Hirax play the London Islington Academy on August 12 and Plymouth Junction on August 13. Faster Than Death will be released on November 1 via Armageddon Records