Language has been a contentious issue since the formation of our nation. The Constituent Assembly debates are rife with discussions about whether Hindi, or any of a number of classical regional languages should be the official language, and whether English was the language of oppression and should be eliminated from the day-to-day affairs of the nation.

When the Constitution came into being, a list of languages was appended in the form of the Eighth Schedule, and Hindi was enshrined as the official language — a decision that causes upheaval to date.

The Constitution and the Eighth Schedule languages

The Constitution deals with the Eighth Schedule languages in only two articles: Article 344(1) and 351.

Article 344(1) envisages Commissions constituted by the President after five years, and then ten years, from the commencement of the Constitution, consisting of a Chairman and members representing the languages specified in the Eighth Schedule to make recommendations to the President for the progressive use of Hindi for the official purposes of the Union.

Article 351 of the Constitution provides that it shall be the duty of the Union to promote the spread of the Hindi language so that it may serve as a medium of expression for all the elements of the composite culture of India. It further makes it the duty of the nation to “secure its enrichment by assimilating without interfering with its genius, the forms, style and expressions used in Hindustani and in the other languages of India specified in the Eighth Schedule.” It also specifies that it may draw upon Sanskrit, and secondarily, other languages, for its vocabulary wherever ”necessary or desirable.”

The Constitution or any supporting documentation does not refer to which languages are to be included in the Eighth Schedule and what criteria they are expected to fulfil. Article 29, however, does say that a section of citizens having a distinct language, script or culture has the right to conserve the same.

Schedule Eight, at its inception, included 14 languages. Sindhi was added later in 1967. Then three more were included in 1992—Konkani, Manipuri and Nepali. In 2004, Bodo, Dogri, Maithili and Santhali were also added to the Schedule.

The Eighth Schedule, at present, consists of 22 languages — Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Urdu, Bodo, Santhali, Maithili and Dogri.

Explore India’s scheduled languages and where they are most spoken below:

The Constituent Assembly’s discussion of language

In 1948, the Linguistic Provinces Commission created a report and presented it to the Constituent Assembly. It warned against organizing states on a linguistic basis, saying that it was not in the “larger interests of the Indian nation”

“Some of the ablest men in the country came before us and confidently… stated that language in this country stood for and represented culture, tradition, race, history, individuality, and finally, a sub-nation,” it said. This commission recommended that the newly free nation adopt a national language.

The Constituent Assembly discussed the subject at great length during its deliberations from November 1948 to October 1949. The then President Rajendra Prasad expressed the importance of this debate saying that there was “no other item in the whole Constitution which will be required to be implemented from day to day, hour to hour, minute to minute”

Even if a particular proposal was passed with a majority, he said, “if it does not meet with the approval of any considerable section of people…, the implementation of the Constitution will become a most difficult problem”.

Among the issues taken up for discussion were:

- The usage of the term official language instead of national language

- Selecting Hindi over languages like Bengali, Telugu, Sanskrit and Hindustani

- Picking the Devanagari script over the Roman script

- What languages were to be used in the Courts and the Parliament

- Whether we should adopt Devanagari or international/Arabic numerals

- Whether English should be used at all

Many who supported Hindi were against the continuance of English in common usage. Meanwhile, some regional leaders were afraid that Hindi would be imposed on States which didn’t speak it, arguing instead for English to be continued as a national language.

Jawaharlal Nehru opined that “no nation can become great on the basis of a foreign language.” While he said that English had done us a lot of good, he expressed fear that the adoption of English would separate “a large mass of our people not knowing English” from a class of elites.

Babasaheb Ambedkar supported Hindi, saying that “Since Indians wish to unite and develop a common culture, it is the bounden duty of all Indians to own up Hindi as their language.”

The pro-Hindi faction in the assembly included K.M Munshi, R.V Dhulekar, Seth Govind Das, Purushottam Das Tandon and Ravi Shankar Shukla—representing Hindi associations across the country. Algu Rai Shastri of the United Provinces referred to Hindi as the national language and asked the President to pass Constitution in Hindi, saying that English was “not the language of the people, not the language of the common man.” He requested the President “in the name of Indian nationalism and in the name of the Indian people” to make an announcement to this effect.

A vocal faction opposed what they called “Hindi imperialism,” with T.T Krishnamachari conveying a “warning on behalf of people of the South” that there were already ”elements who want separation.”

“It is up to my friends in U.P to have a whole-India; it is up to them to have a Hindi-India. The choice is theirs.” he said.

A few voiced their support for Sanskrit, the “revered grandmother of languages of the world” as Lakshmi Kanta Maitra described it in a speech to the Assembly. Others, including, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, were in favour of Hindustani, which would derive sustenance from both Hindi and Urdu.

Nehru also warned the nation to be on its guard while adopting Hindi. “Some speeches I have listened (to) here,” he said, “there is very much a tone of the Hindi speaking area being the centre of things in India, the centre of gravity, and others being just the fringes of India.”

It was, of course, Hindi that was eventually adopted — under Article 343 of the Constitution, Hindi in the Devanagari script was declared the official language of the Union. However, the provisions relating to it were formulated only after a compromise that English would continue to be used as an official language for 15 years. Post this it was expected to wither away as the country and its states transitioned completely to Hindi. Importantly, Hindi was also not declared the “national” language.

The warnings of the Linguistic Provinces Commission about the dangers of linguistic division, however, proved futile as by 1953 the central government had to organise its first linguistic State — Andhra Pradesh. A States Reorganization Commission was appointed in 1954, submitted its reports in 1955, and its recommendations went into effect after November 1, 1955.

Clashes over the official language

Regional concerns over a possible imposition of Hindi continued well past the adoption of our Constitution.

In 1959, Paul Friedrich wrote that a political drift called the ‘balkanization of the South and the consolidation of the north’ was taking place in India, quoting an archival article by the Hindu from 1959.

That same year, Jawaharlal Nehru assured the States that English would remain in official use and as the language of communication between the Centre and the States.

In 1963, the Official Languages Act was passed, as the 15-year window for the use of English drew to a close. It came into force on January 26, 1965, 15 years after the Constitution was adopted. But since the Official Languages Act, 1963, did not expressly state a commitment to the continuance of English, States were nervous as the January 1965 date for the enforcement of the Act drew near.

Moreover, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri also restated that the government was committed to making Hindi the official language

Protests broke out in Tamil Nadu in January 1965 against what was perceived as the imposition of Hindi, mainly in Tamil Nadu. Spearheaded by the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, the protests were violent — protestors self-immolated and more than 60 people died in the following days.

The protests only abated once Congress leaders K. Kamaraj, N. Sanjiva Reddy, and Nijalingappa met with the then Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, who said documents would continue to be bilingual indefinitely.

These protests also resulted in an amendment of the Language Act by Indira Gandhi, which ensured that English would continue to be used as an official language, till the stage where resolutions for the “discontinuance of the use of English language…have been passed by the legislatures of all the states, which have not adopted Hindi as their official language.”

In 1976, the Official Language Rules were framed, and it was emphasised that they applied to the whole of India, but not to Tamil Nadu.

The three-language formula

Aiming for a more linguistically consolidated nation, the Centre proposed a new education policy in 1968. It envisages the teaching of three languages in schools — English, Hindi and one regional language in the Hindi-speaking States, swapped out for the official regional language in the other States.

In practice, this is rarely followed. Hindi-speaking States seldom teach a third language. Tamil Nadu, always a vociferous opponent of Hindi imposition, has stuck to a two language formula.

Schedule Eight languages are not official languages

Despite their inclusion in the Constitution, the Eighth Schedule languages are as yet not considered official languages, and leaders have called for this change.

In February 2021, a Bhasha Bharata Round Table Conference organised by the Karnataka Development Authority in Bangalore with representatives of 17 languages adopted a “Bengaluru Resolution,” calling on the Centre to amend Article 343 of the Constitution to make all languages listed in the Eighth Schedule official languages of the Union.

The Resolution asks that all laws, rules, and notifications be published in all the 22 languages of the Eighth Schedule. It also seeks that the Union government hold entrance and recruitment exams to educational institutes in all 22 languages.

Meanwhile, in June 2021, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K Stalin said that the DMK government would strive to make all languages in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution, including Tamil, part of the Union government’s administrative and official languages.

Adding to the Eighth Schedule

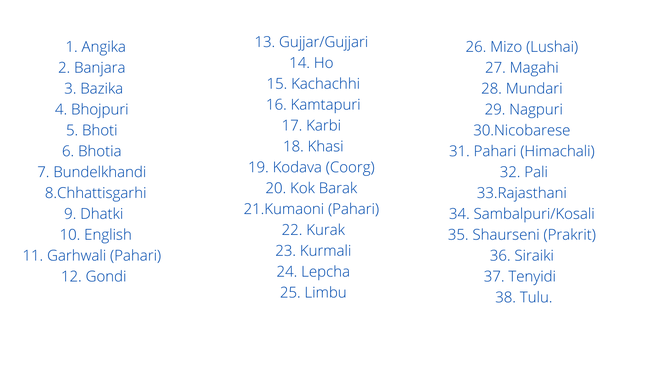

At present, there are demands to include 38 more languages in the Schedule. Committees were set up in 1996, under Ashok Pahwa, and 2004, under Sita Kant Mohapatra, to evolve a set of objective criteria for the inclusion of languages in the Eighth Schedule. These efforts have, however, proved inconclusive.

Languages sought to be added include Bhil, with more than one crore speakers as per the 2011 census, Gondi, with 29 lakh speakers as per the 2011 census, and Tulu, with 60 lakh speakers.

Here is the complete set of languages which seek inclusion: