The Dictionary of Lost Words follows Esme as she navigates the patriarchal world of Victorian England. While her father and colleagues construct the Oxford English Dictionary, Esme begins to form her own dictionary – particularly the words spoken by women and the working class who have been excluded.

Along the way she is buffeted by the seismic events of the early 20th century in the suffrage movement and the first world war.

Verity Laughton’s stage adaptation of Pip Williams’ best-selling book is a wonderful work.

We are introduced to a crusty world of dedicated male lexicologists who are gathered together in the shed, or “scriptorium”, of Sir James Murray, played with erudite Scottish enunciation by Chris Pitman. They valiantly set out to construct volumes of meaning for words from the letters of the alphabet – with a hint of empire-building about the enterprise.

Read more: Book review: The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

A brilliant innovation

Tilda Cobham-Hervey makes a standout return to the stage carrying the central character of Esme.

We first see her as an ingénue child hiding under the large desk of the eminent lexicologists. Her direct address to the audience draws us into her perspective of what is occurring around her.

As she grows, her curiosity about the world deepens while her determination to be her own person strengthens, in spite of the limited opportunities for women. Cobham-Hervey navigates this journey of discovery and identity formation with a surety of purpose and endows Esme with a passion for words and their meaning.

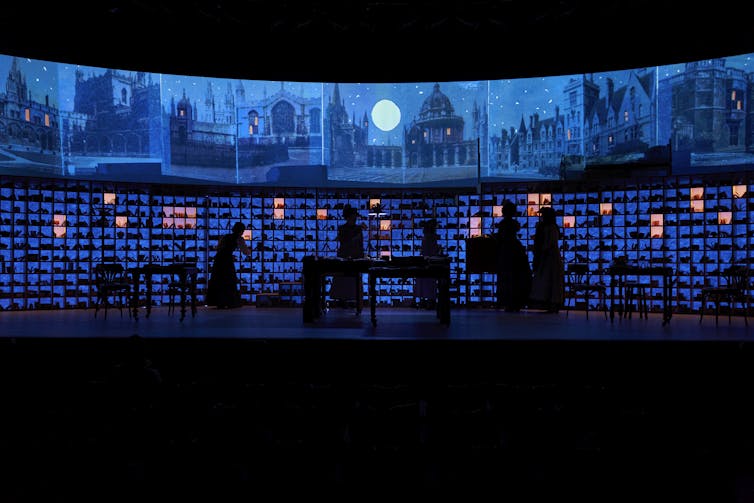

In a brilliant innovation from designer Jonathon Oxlade we see words handwritten and projected from a camera hidden within a lamp above the central desk. This also enables the cast to indicate the location and the passing of time at the beginning of each scene – always a challenge when moving across the many scenes a novel brings. Postcards from locations are projected on a curved back-screen that echoes the diorama and magic lantern popular at the time.

Below the screen are immense rows of pigeonholes where the slips of paper containing word meanings are filed. In a neat twist, these pigeonholes become letterboxes as Esme distributes pamphlets for the women’s movement when she is converted to the cause by the suffragette Tilda, given appropriate boldness by Angela Mahlatjie.

Lighting designer Trent Suidgeest sweeps diverse colours across the pigeonholes, also lit within, with the various hues accompanying the emotional arc of the play.

Composer Max Lyandvert adds fine and sensitive nuances to his score, which heightens the total theatre nature of the experience. A stylised version of Auld Lang Syne becomes a motif for the passing of those close to Esme, notably her father Harry, given dignity and depth by Brett Archer.

A beautiful realisation

Director Jessica Arthur handles the cast and use of video well. An inspired touch is having the ensemble move slowly behind key monologues and duologues, adding intricate detail. When Esme gives birth we see her mouth magnified by the live camera, in a close-up that amplifies the intensity of the birth.

Cobham-Hervey is supported by a fine ensemble who succinctly double up as required in Laughton’s economy of writing. Rachel Burke brings dynamism to Lizzie Lester, Esme’s “bondmaid”. Ksenja Logos doubles well between Esme’s supportive aunt and the rowdy and endearing market stallholder Mabel.

The market scene is one of the triumphs for the ensemble as it bustles with liveliness. The audience explodes with laughter as Esme discovers swear words though the indomitable Mabel.

In the quieter second half, Raj Labade brings a warmth to Gareth, Esme’s suitor. Esme must first confess her dalliance with a former lover, Bill Taylor, played by Anthony Yangoyan with rakish charm. This is brilliantly shown by the ensemble as a flashback, where Esme has to make the agonising choice between keeping her illegitimate child, with the social consequences of the time, or giving her child away, with the accompanying grief that would follow.

As with Williams’ book, the play ends with an abrupt shift to 1989 and to Esme’s long-lost daughter who begins a speech with the Kaurna welcome “Niina marni”.

Williams’ intention is to highlight that the struggle for inclusivity continues, in particular for Indigenous languages. However, having spent so long with Esme, this feels like a rupture within the narrative – which indeed may be the purpose.

“Realised” might be defined as to give shape to an artform. This is a very clever realisation of Williams’ novel for the stage and gives great power to key moments of this epic story.

The Dictionary of Lost Words is at the State Theatre Company of South Australia until October 14, then at the Sydney Theatre Company from October 26 to December 16.

Russell Fewster has worked with State Theatre Company of South Australia in co-ordinating the second year course State Theatre Masterclass at the University of South Australia.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.