When South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law this week it was the first time a South Korean government took such a drastic measure since it became a fully functioning democracy more than 35 years ago.

But in the decades of largely autocratic governments and military rule from the end of World War II until the establishment of the Sixth Republic in 1988, martial law was not uncommon as the country faced political turmoil, uprisings, frequent protests and all-out war with North Korea.

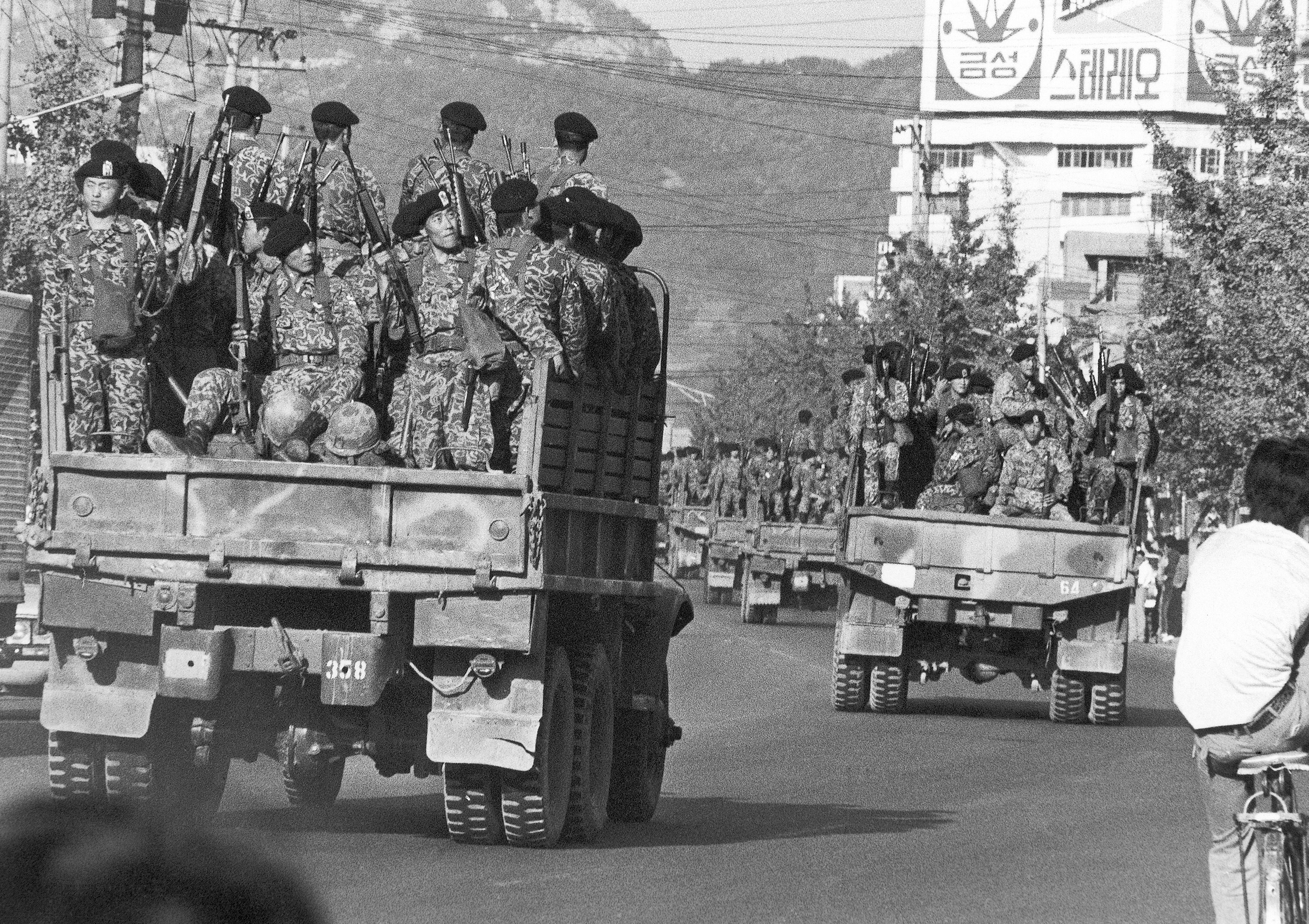

It was last imposed in 1979 by Prime Minister Choi Kyu-hah after the assassination of President Park Chung-hee, a military dictator who had seized power in a 1961 coup. It was then extended in 1980 by Gen. Chun Doo-hwan, who also took the presidency in a military coup.

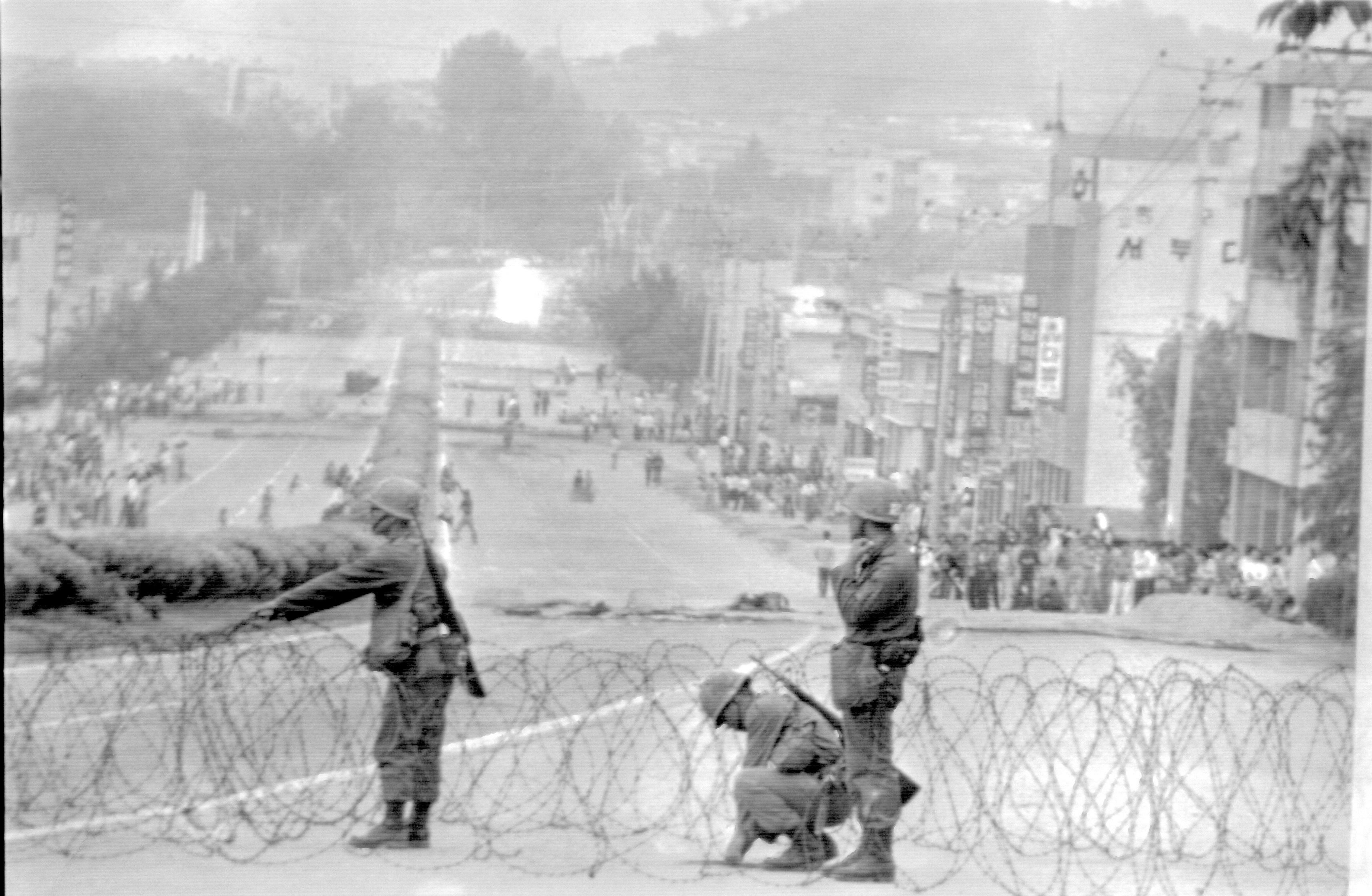

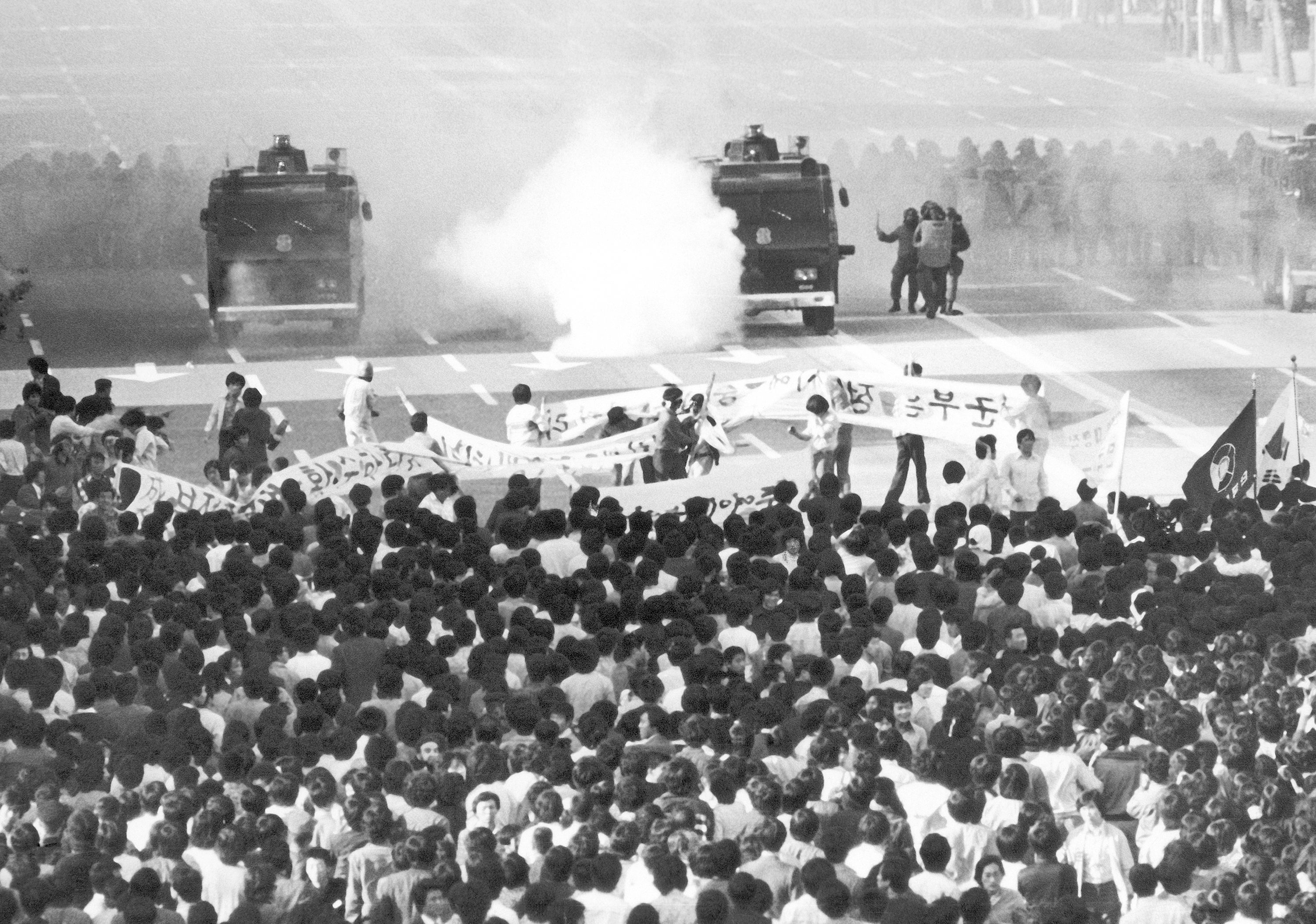

He used military force to put down student-led demonstrations in Gwangju, some 250 kilometers (150 miles) south of Seoul, killing hundreds of protesters.

In Seoul, thousands of university students took to the streets to demand an end to martial law, and were confronted by riot police using tear gas. Martial law was eventually lifted in 1981.

Martial law was first used in 1948 by South Korea's first president Syngman Rhee as he cracked down on communist uprisings, killing thousands.

It was also invoked during the 1950-53 Korean War to allow South Korea to use its military to stifle anti-government protests.

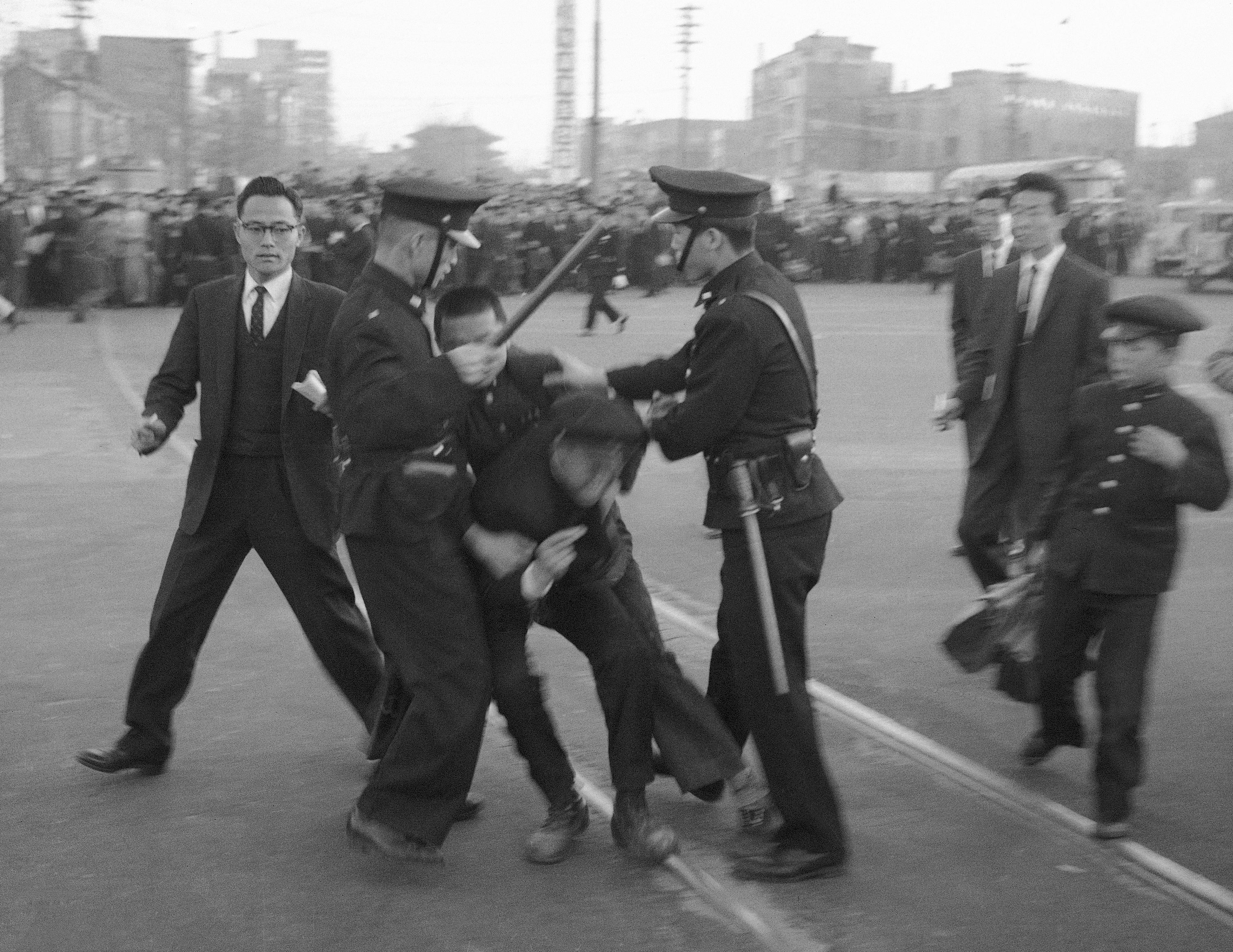

As Rhee struggled to hold onto power in the face of growing opposition, he imposed martial law again in 1960. Hundreds were killed in clashes between protesters and police. After Rhee was forced to resign in the face of nationwide demonstrations, jubilant South Koreans climbed aboard a tank outside Seoul's City Hall to celebrate.

While still president in 1972, Park Chung-hee initiated another coup to give himself dictatorial powers and declared martial law, again sending tanks into the streets of Seoul. It was lifted later the same year.

Through the years until his assassination in 1979, protests against Park's rule grew, and he used emergency measures to justify the jailing of hundreds of dissidents.