Frank Gehry's name is said in the same breath as those of leading architects of the 20th and 21st centuries – including Herzog de Meuron, Rem Koolhaas and Tadao Ando. The Los Angeles-based architect and his practice, Gehry Partners, became prolific pioneers of building design through Gehry’s expressive experimentations with form, space and material, challenging the status quo with their intensity, allure and unexpected nature. It earned him the prestigious 1989 Pritzker Architecture Prize – and that was just one in a long series of recognitions for the architect, including a Guest Editorship in the Wallpaper* October 2014 edition. Now, in his 100th decade, Gehry shows no signs of slowing down – building and nurturing the next generation of architects in his office.

In an interview with Wallpaper* in 2011, he said: 'The best thing [that could happen] for me is to train these young guns [partners in his firm] and mother-hen them out into the world and watch like a proud papa while they grow. That's my dream.'

Frank Gehry: a brief history

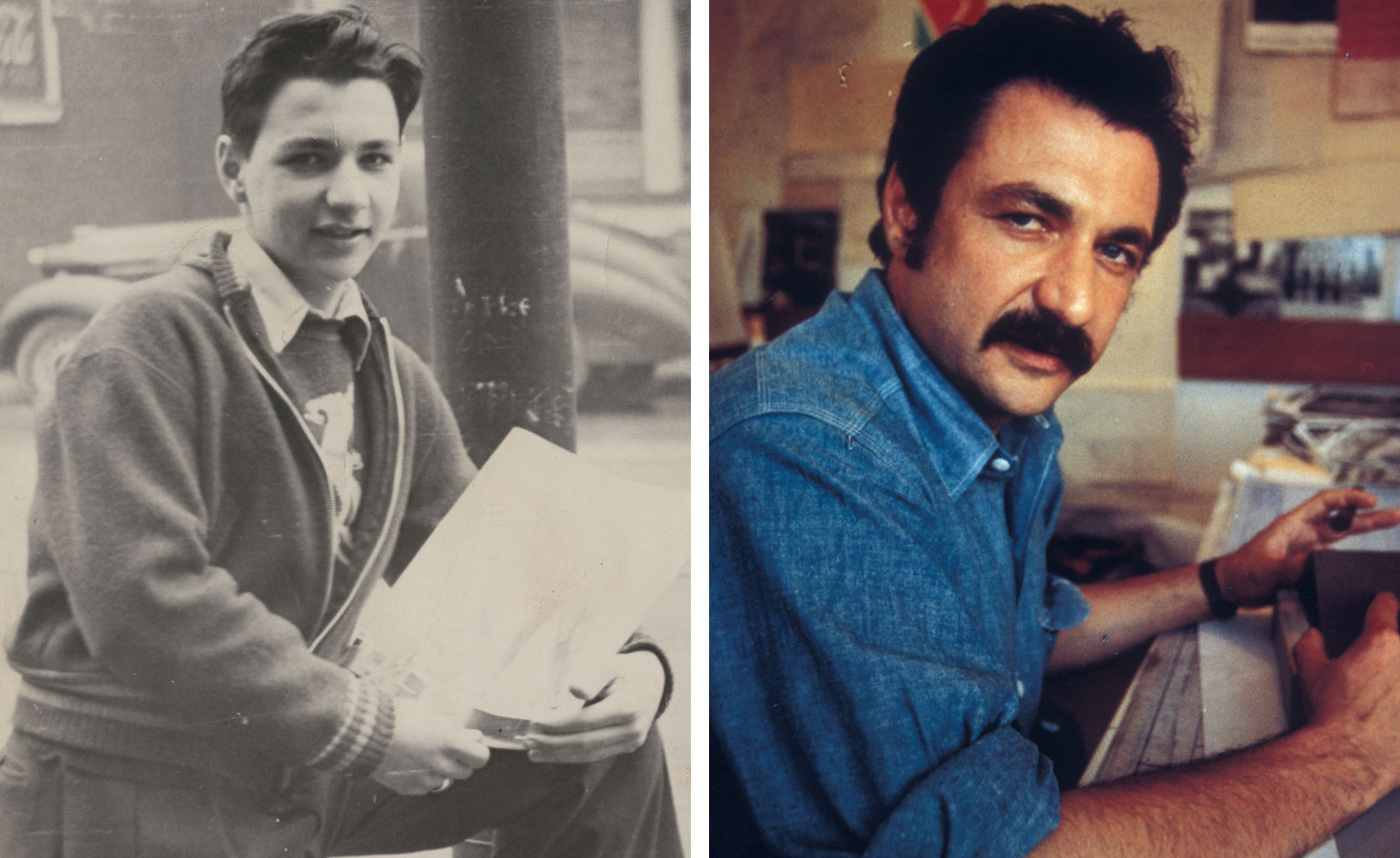

Canadian-born American architect Frank Gehry (b. 1929) famously explored becoming a truck driver and a chemical engineer before landing on architecture – a profession that attracted him because of its strong relationship with art, a field he was naturally drawn to and which he often explored through his designs. His belief that 'architecture is art' has been part of his approach since day one – his appreciation for sculpture, in particular, was highlighted when he won the Pritzker, citing artists as some of his key 'idols'.

Gehry graduated from the University of Southern California before working full-time at Victor Gruen Associates, serving a year in the army, and being admitted to Harvard Graduate School of Design's urban planning course. He later worked for Pereira and Luckman. A second stint at Gruen led to a year's stay in France and finally, Gehry’s return to Los Angeles and setting up shop on his own in 1962.

Right from the start, his work experimented with rough, even industrial materials and forms – he often works with steel and titanium sheets to this day. Chain-link fencing and 'unfinished qualities' are also frequently found in his designs – in particular, early-day ones – which are distinctive and often instantly recognisable for their dynamic shapes and bold compositions.

‘His sometimes controversial, but always arresting body of work has been variously described as iconoclastic, rambunctious and impermanent, but the jury, in making this award, commends this restless spirit that has made his buildings a unique expression of contemporary society and its ambivalent values,' the Pritzker Prize jury wrote in their citation in 1989.

His career spans buildings of all typologies and sizes – from offices to pavilions, and from single-family houses to skyscrapers. Gehry has also worked with the smaller scale, creating furniture pieces that resemble sculptural works of art. His portfolio in objects and products includes a line of furniture for Knoll, jewellery for Tiffany & Co, a limited-edition bottle for Hennessy cognac in 2020, and limited-edition sculptural bags for Louis Vuitton.

Gehry is also the force behind what has been called the 'Bilbao effect'. Completing his Guggenheim museum in Bilbao in 1996 propelled the relatively small town in Spain's Basque Country into the global spotlight, completely transforming its fortunes in one fell swoop – this demonstrated the power of contemporary architecture in an unparalleled way.

Asked about how his career changed after Bilbao, in our 2011 interview, he said: 'There's a measure of credibility that accrued to me after Bilbao. It wasn't only that it made the community happy, it earned a lot of money for the community and revenues for the city. And the building was built on budget. So all of those things were helpful. And when I go there, people seem very happy with the building – the Guggenheim people are happy and a lot of the artists are happy. There are some diehard curators out in the world and museum directors who think that's the wrong way to show art and they still grumble about it, but that hasn't been proven correct in show after show. So it's just some kind of grumble.'

And while Gehry is considered by many one of the original 'starchitects' of the 20th century, he remains sceptical about using the term 'iconic architecture'. In the same interview, he said: ' I think history has shown that there's a need for iconicity in public buildings because they become a source of pride for the community. The Greeks, the Romans, up until present time, we've always focused on public buildings as having architectural importance. It's the accumulation of these buildings as icons that identifies the community. What's happening in the world today is everything is iconic.

'It seems that we're starting the baby steps of a new language or new paradigm for city building. And there's now a backlash against that. But that means you go back to the 1960s where you build boxes, banality. That seems wrong. Seems we've been there before. But there's a move by artists now to jump into the fray, to bring character and beauty to cities. They have offices as big as mine, and they know how to build. A lot of artists have big projects in mind, like Olafur Eliasson and Anish Kapoor, and they have the finances, the contacts and the technical resources to develop big things, as big as the Eiffel Tower, probably. There's a lot of talented artists out there who have a lot more juice than some of the banal box guys. I welcome them.'

Frank Gehry's key architectural projects

Gehry House, Santa Monica, USA (1978)

The home of Gehry and his family, this 1920 home in Santa Monica, California was redesigned and extended by the architect in 1977. It features a metallic exterior wrapped around the original building, wrapping the period structure with a rougher, utilitarian envelope that displays hints of the architect's passion for dynamic volumes and intense geometries.

Nationale-Nederlanden Building, Prague, Czech Republic (1996)

Completed just one year before what is likely Gehry's most famous project, the Guggenheim in Bilbao, the Nationale-Nederlanden Building in Prague was created together with Croatian-Czech architect Vlado Milunić. It's easy to see why this office was nicknamed Dancing House, or Ginger and Fred – its dynamic outline evokes the image of a pair in a dancing embrace, skirt twirling and top hat on.

Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain (1997)

The transformative effect of architecture is exemplified at its finest in Guggenheim Bilbao. The project, completed in 1997, took a slightly rough-the-edges port town and turned it into a cosmopolitan city with a world-class art museum the crowds flock to visit to this day. ‘There’s two Bilbaos: the one before Guggenheim, and one after,’ said the museum’s director, Juan Ignacio Vidarte ahead of ‘Reflections’, a week-long celebration of its 20th birthday in 2017.

Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, USA (2003)

Echoing the success of Bilbao, the Walt Disney Concert Hall now instantly conjures up images of downtown LA, where it is located, on 111 South Grand Avenue. Gehry was commissioned to design it a little before being announced as the recipient of the Pritzker in the year he won (1989), and it was his first major project in his hometown of Los Angeles.

IAC Building, New York City, USA (2007)

Gehry also designed the headquarters of American holding company IAC in Manhattan. Completed in 2007, it was the architect's first completion in New York and defines its waterside location with flowing, ethereal forms and reflections that seem to evoke ripples on water or waves. Its form, clad in translucent glass instead of the titanium sheets used in Bilbao or the Walt Disney Hall, consists of a group of twisting towers which come together on the base and emerge slimmer towards the top.

Serpentine Pavilion, London, UK (2008)

The ninth in the famous series of the Serpentine Galleries' architectural pavilions, Gehry's design was mostly made out of wood and engineers with the help of Arup. He said at the time: 'The pavilion is designed as a wooden timber structure that acts as an urban street running from the park to the existing gallery. Inside the pavilion, glass canopies are hung from the wooden structure to protect the interior from wind and rain and provide shade during sunny days. The pavilion is much like an amphitheatre, designed to serve as a place for live events, music, performance, discussion and debate.'

8 Spruce Street, New York, USA (2011)

8 Spruce Street, previously known as the Beekman Tower and New York by Gehry, is a New York high-rise that was the tallest in the Western Hemisphere when it first opened in 2011. The mixed-use tower blends residential with retail spaces, alongside a school, hospital and amenities.

Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France (2014)

Commissioned by Bernard Arnault, the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris, located within the green fields of the Jardin d'Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne, is a masterpiece of flowing forms and lightness. The structure is a composition of white blocks (also known as 'the iceberg'), featuring 12 curving glass 'sails', supported by wooden beams. Gehry was inspired by the lightness of 19th-century glass and garden architecture, and placed inside 11 exhibition galleries for temporary and permanent shows from the foundation's collection. The project also includes an auditorium, meeting rooms, a café, a bookshop and education facilities. The views from the top terraces stretch across the park.

Luma Tower, Arles, France (2021)

Gehry's twisting, geometric Luma Tower is the unquestioned architectural centrepiece of Luma Arles. Set at Parc des Ateliers, a 27-acre campus, the project is finished with 11,000 stainless steel panels, and boasts the American architect's vision for creating otherworldly, gravity-defying structures. The 15,000 sq m space will be home to exhibition galleries, project spaces and the foundation's research and archive facilities, alongside workshop and seminar rooms.

Prospect Place at Battersea Power Station, London, UK (2022)

Prospect Place at London’s Battersea Power Station is Frank Gehry’s first residential building in the UK. Comprising two buildings and a total of 308 homes, the scheme was recently completed and welcomed its first occupants in 2021. ‘I love London,’ said Gehry at the time. ‘It has culture, history and diversity and the buildings we have created at Battersea Power Station are designed to stand artfully on their own amongst all of that, whilst also framing an internationally recognised icon.'