The plane was flying over paradise, carrying 95 people on a short jaunt from Hilo to Honolulu in Hawaii, when all hell broke loose in an instant on the afternoon of 28 April 1988. There was a “whoosh” sound and then chaos; the blue sky the plane was traveling across suddenly came rushing through the cabin as the fuselage appeared to be disintegrating.

A flight attendant — along with some of the aircraft — vanished. Neither would ever be seen again.

In the ensuing 13 minutes of terror, the pilots of Aloha Airlines Flight 243 somehow, miraculously, managed to land the damaged plane. Veteran crew member Clarabelle “C.B.” Lansing was the tragic sole fatality, while 65 others suffered injuries during the traumatising, tumultuous flight — but the ordeal highlighted heretofore-unexplored problems with the continued airworthiness of aging planes.

“We had never had airplanes flying for that many years, or that many flight cycles, in this sort of set of circumstances,” Jeff Marcus, chief of safety recommendations for the National Transportation Safety Board, tells The Independent. “And unfortunately, that’s the way, many times, that lessons are learned; that’s the reason why the NTSB exists, you do an investigation after something unfortunate occurs, and you learn from that.

“The lessons from Aloha were far-reaching,” he says.

Nothing, of course, had seemed amiss to cabin or maintenance crews who’d worked on the Boeing 737 before it fell apart mid-air on that fateful April afternoon. The plane, tail number M73711, had already flown three inter-island round trips and passed inspections that day before Flight 243 took off at 1325 with First Officer Madeline “Mimi” Tompkins, 37, at the controls and Captain Robert Schornstheimer, 44, performing nonflying pilot duties. An FAA air traffic controller was seated in the observer seat in the cockpit, while flight attendants Michelle Honda and Jane Sato-Tomita completed the crew, along with 58-year-old Lansing.

Taxi and takeoff were uneventful, but everything changed 20 minutes into the flight as the plane leveled at 24,000 feet.

“All of a sudden, I heard a loud noise, a bang, but not an explosion, and felt a strong pressure change,” passenger Eric Becklin, who was sitting at the back of the aircraft, told The Washington Post in the days after the flight. “I looked up front and saw the front of the top left of the airplane disintegrating, just going apart, pieces of it flying away. It started with a hole about a yard wide, and it just kept coming apart.”

With it, tragically, went Lansing, who had been standing around the fifth row of seats in the first class section of the aircraft.

“She was just handing my wife a drink,” passenger William Flanigan, 54, told the Post in 1988. “She had stopped and told us this was the last call. We were going to be descending. And then, whoosh! She was gone. Their hands just touched when it happened.”

The pilots in the cockpit, equally stunned, quickly sprung into action after the initial bang that “sounded like really heavy canvas ripping rapidly,” Captain Schornstheimer told The Maui News in 2018.

“It happened almost instantaneously,” he said. “There was no warning.”

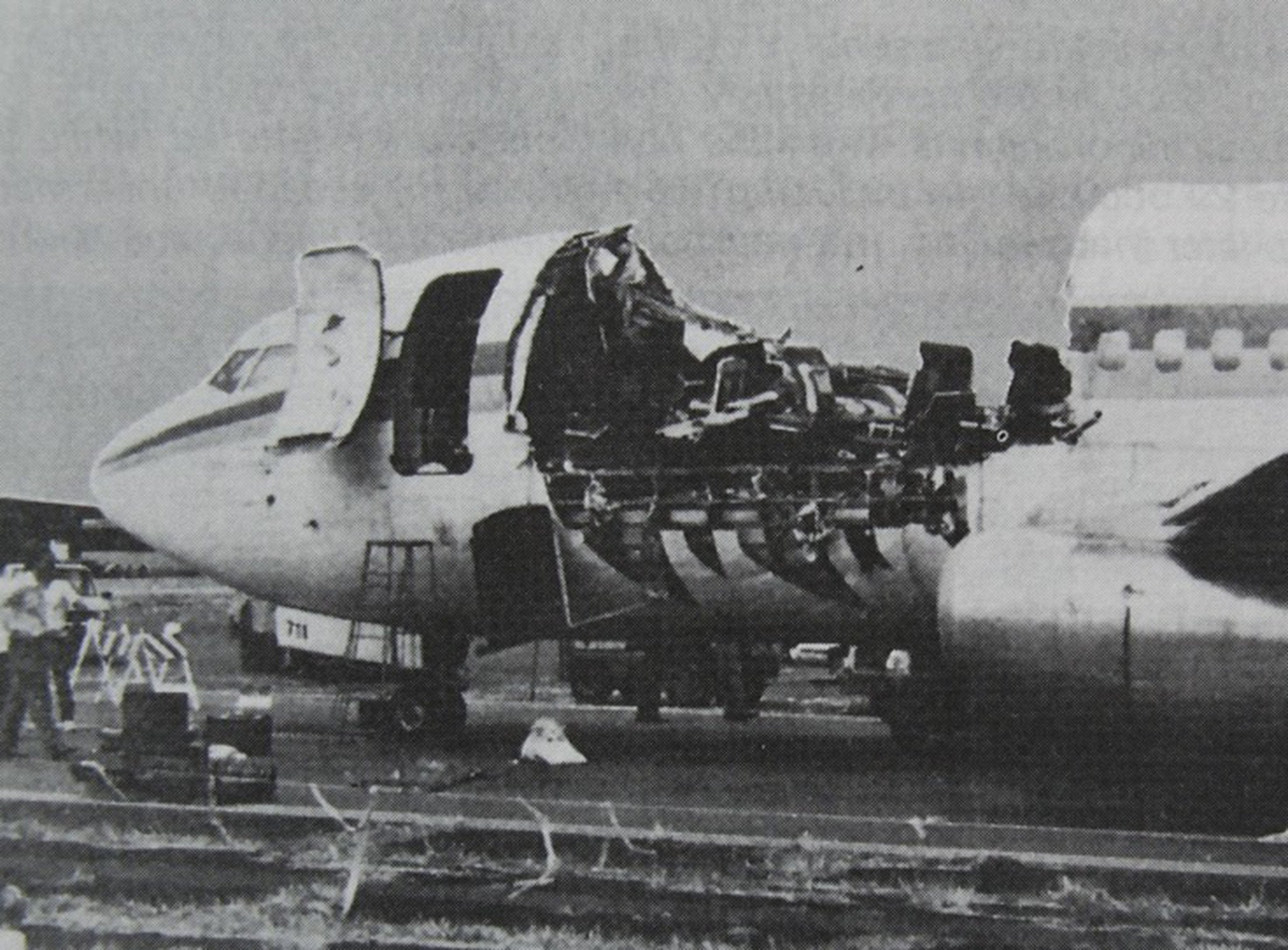

Ms Tompkins’ “head was jerked backward” as pieces of debris, including insulation, floated through the air; the cockpit door was gone and “there was blue sky where the first-class ceiling had been,” the captain told investigators, according to the NTSB report.

“It was actually almost like being in a dream at that point because it’s so unexpected your mind tries to protect you from what’s going on,” Mr Schronstheimer told The Maui News around the incident’s 30th anniversary. “You’re just sort of dazed. I did turn right back around and put my oxygen mask on as I was trained to. I signaled to my co-pilot I was taking control of the airplane.”

The controls felt “loose,” he told investigators, and the plane rolled “slightly left and right,” according to the report.

Meanwhile, passengers in the cabin — and the remaining flight attendants — were struggling to collect themselves physically and mentally.

“I remember thinking about things like, ‘I don’t have enough life insurance,’” Mr Becklin told The Maui News. “But there’s nothing I could do about that. And I tried to get some peace with the world, but there was too much noise and too much debris flying around, so that never happened.”

Flight attendant Ms Sato-Tomita was knocked unconscious by flying debris and lay on the floor, bleeding.

“The first time I saw her I thought she was dead,” fellow attendant Ms Honda, who had been standing around row 15, told The Washington Post in the days after the incident. “She was just on the borderline of the hole. Her head was split open in the back. She was under debris.”

Ms Honda, too, had been thrown to the floor but sustained only minor injuries — and dutifully scrambled to help terrified passengers anyway she could.

“I had no sense of rows, only seats,” she told the newspaper. “I was crawling and dragging ... I know I was on my back some of the time because of the perspective of looking up into their faces. I don’t know when I stood up or when I crawled.”

Comparing the atmosphere to a “blizzard,” she continued: “There was smoke-like vapor in all the debris flowing around — paper, fiberglass, asbestos. It was kind of white ... The passengers were reaching out and holding me as I went by and I grabbed their arms.

“The closer you came to the hole, the more intense the wind was. I didn’t know if I would have stayed in the aircraft if I let go, and I wasn’t about to find out.”

One of her passengers, Mr Becklin, later said he was convinced the plane “was going to fall apart before [the pilot] could land it.”

Mr Schornstheimer, however — an Air Force veteran — initiated an emergency landing as Ms Tompkins attempted to radio ahead for help.

“I was just totally focused on having to make it,” the older pilot told The Maui News. “I didn’t have time to dwell on what would happen if I didn’t.”

Emergency personnel on the ground could not believe what they were seeing as the damaged plane approached.

“It looked like it was going to crash,” Larry Miller, who’d been the Aloha Airlines assistant station manager at the time, told outlet. “There was part of it missing. The whole top of the fuselage was gone. . . . I didn’t possibly think that this plane could land.”

At 1.58pm, however, the plane touched down miraculously at Maui’s Kahului Airport with no further casualties.

“It was remarkable flying on the part of the two pilots to be able to land that airplane after that happened,” Mr Marcus tells The Independent, more than three decades after the aviators’ life-saving feat.

SIxty-five people on the plane were injured, eight of them seriously, and the ground response teams were unprepared for the magnitude of the incident; there weren’t enough ambulances, so victims were ferried in tour company vehicles for treatment.

“We were shuttling more than one person in the ambulance at a time,” Mr Miller told The Maui News. “We did what we had to do to get people to the hospital.”

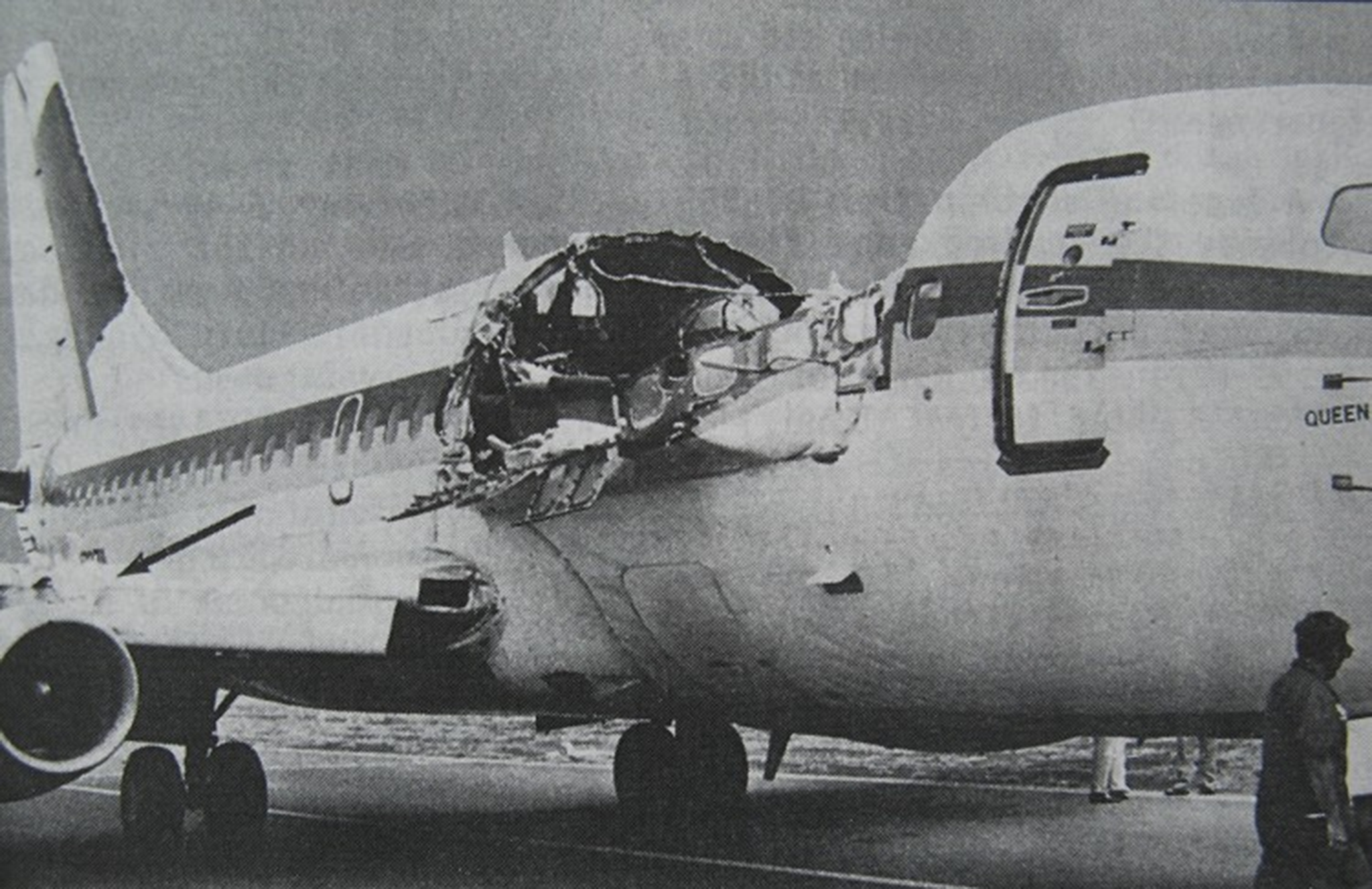

Unsuccessful searches were launched for Ms Lansing and parts of the airplane — as focus quickly turned to what had gone wrong.

At the time of the accident, according to the NTSB report, the plane “had accumulated 35,495 flight hours and 89,680 flight cycles (landings), the second highest number of cycles in the worldwide B-737 fleet.”

On its final flight, however, the plane suffered explosive decompression as a result of structural failures caused by “significant disbanding and fatigue damage.”

“As you go up in altitude, the air pressure outside reduces, so an airplane has systems that keep the air inside the airplane sort of the same pressure as it would be when you’re near the ground. When the skin blows out, then all of that air inside the airplane suddenly goes flying out, because it’ slow pressure out there, and that’s explosive decompression, because it happens very quickly,” Mr Marcus tells The Independent.

He explains: “When the decompression occurred ... the outer skin for a big part of the airplane just flew out, and that affected the structural integrity of the rest of the airplane.”

Thanks to “a few happy coincidences,” however, he says that “parts of the skin remained attached that prevented the nose of the airplane from falling off.” There was still, however, damage to the wings, tail and left engine.

According to the NTSB report, a “passenger stated that as she was boarding the airplane through the jet bridge at Hilo, she observed a longitudinal fuselage crack. The crack was in the upper row of rivets along the S-10L lap joint, about halfway between the cabin door and the edge of the jet bridge hood. She made no mention of the observation to the airline ground personnel or flightcrew.”

All of that, investigators determined, could likely have been avoided had more meticulous safety inspections and protocols been practiced. The accident led to more frequent and thorough checking of aircraft cracks and rivets after there was “obviously a failure of the maintenance program to catch these impending errors and repair them,” Mr Marcus tells The Independent.

The NTSB report found that “the probable cause of this accident was the failure of the Aloha Airlines management to supervise properly its maintenance force” and “the failure of the FAA to evaluate properly the Aloha Airlines maintenance program and to assess the airline’s inspection and quality control deficiencies,” among other factors.

But this week, paraphrasing a late NTSB colleague, Mr Marcus says: “In essence, this was not something we could have reasonably foreseen.

“It was unfair to say the FAA ignored issues with the maintenance department; it was unfair to say that Boeing had not done adequate engineering,” he says. “It was a case of: This was just something we didn’t know before.”

Hazel Courteney, president of the International Federation of Airworthiness, says that the factors behind the Aloha Airlines accident were “not as if someone was just flagrantly not doing their job; everyone was trying to do their job.”

The advice from Boeing, she tells The Independent, “was not really calibrated around aircraft that worked that hard, so Aloha probably should have made a tighter program up — [but] they went with the kind of default program ... but the program wasn’t quite good enough for what the aircraft was being asked to do, and the training wasn’t quite enough for people to really spot what they should have spotted, and the culture was encouraging people to have the aircraft ready. So it’s all those kinds of subtle things.”

The April 1988 incident, she says, “sparked significant change, really.”

“It’s sparked a lot of attention to aging aircraft and how we manage them,” she says. “I think it gave everyone a shake, and made everyone think, you know, we really do need to look at what we’re doing and whether it really does meet the standard.”

Mr Marcus tells The Independent: “There were a number of revisions of so a lot of focus within the aviation industry on aging aircraft — so Aloha, to my mind, kickoff that whole focus.

And safer skies are, perhaps, a befitting legacy for Lansing, who dedicated so much of her life to the airline and its passengers.

The flight attendant “was the nicest old-timer there that knew her customers, her regulars,” said former station manager Mr Miller said in 2018. “She called them by first name. She called me by my first name. That was something to me. She was total Aloha customer service. She was the textbook model of a good stewardess.”

Mr Schornstheimer remembered her similarly, recalling Lansing to The Maui News as among the “most strict flight attendants with the cabin crew” while forming long-term friendships with passengers.

She was known for always wearing “a garden of flowers in her hair, not one or two,” her former coworker Mr Miller said — and, appropriately, there is a memorial garden named for Lansing at Honolulu International Airport.

“Her life was the airline,” Mr Schorntheimer said in 2018, 30 years after captaining her final flight and miraculously piloting the remaining souls to safety.

Despite the passage of time and the tragedy’s enduring safety legacy, he said the full import of those events more than 30 years ago remained with him: “You never really get over it.”