They say everyone has a book inside them. Some people are unfortunate enough to have more than one.

Lech Blaine’s first memoir, the acclaimed Car Crash (2021), dealt with the fallout of a motor vehicle accident that killed three of his mates and traumatised everyone else involved – including Blaine, who’d been riding shotgun when his friend’s Ford Fairlane veered onto the wrong side of the New England Highway on a Saturday night in 2009.

In his latest offering, the gloriously titled Australian Gospel, the car crash you can’t look away from comes in the form of Michael and Mary Shelley – the estranged, deranged parents of three of Blaine’s foster siblings.

Review: Australian Gospel: A Family Saga – Lech Blaine (Black Inc.)

Michael and Mary Shelley are a pair of nomadic Christian fanatics, who, under God’s good guidance, spend their time kidnapping children, stalking politicians, threatening pontiffs, harassing social workers and letter-bombing hardworking, good-natured people like Lech’s parents, Tom and Lenore Blaine:

AS GOD’S CHOSEN PROPHETESS, I GIVE YOU A FINAL WARNING FROM GOD. I NEED MY DAUGHTER HANNAH RETURNED TO MICHAEL + I TODAY WITH APPROPRIATE COMPENSATION ($100,000 WOULD BE A NICE START) OR GOD WILL SEND HIS NEVERENDING WRATH UPON YOUR HEAD.

Failure to thrive

To say the Shelleys are incensed their children have been taken away from them and given to the Blaines to raise as their own is putting it mildly.

The familial exodus starts with toddlers Saul and Joshua, who in 1986 are removed from the birth parents for “failure to thrive” and renamed Steven and John to keep them hidden and protected from the Shelleys. (Just three years earlier, the pair had been arrested for kidnapping their eldest son Elijah from his foster parents.)

But it goes on to include the boys’ baby sister Hannah as well, who takes up residence in the Blaine household under similar circumstances some five years later, in 1991.

The Shelleys’ outrage is exacerbated by the cultural incongruence between the families’ two patriarchs. The archangelic Michael abhors the average Australian male, who can think of nothing better to do with his time than sink piss, watch football and eat meat pies.

Meanwhile, the archetypal Tom, a publican obsessed with rugby league, is the sort of guy who makes The Castle’s Darryl Kerrigan look like some sort of interloping dandy hot off the plane from gay Paris – which Tom visits at one point, on a Kangaroos tour. (He can’t vacate the “shithole” of a place fast enough.)

The memoir is littered with threatening correspondences like the one excerpted above. All of them are variations on the same vindictive, desperate theme. It is a credit to Blaine’s curatorial skills, however, that my readerly reaction continued to evolve over the course of the story.

I was shocked, amused and finally sympathetic to the Shelleys’ apocalyptic ALL CAPS antics. These people are clearly not well. In fact, they met in a psychiatric hospital, where Mary Shelley was diagnosed with bipolar. A social worker describes Michael Shelley as “human proof of narcissistic personality disorder”.

All sentences are created equal

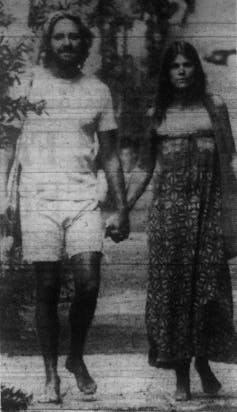

Given the volatility and inherently dramatic potential of the source material – a family hiding out in rural Queensland from a pair of would-be abductors who resemble Jesus and Mary Magdalene – Blaine could easily have adopted a sensationalist tone and played for maximum gasps, laughs and/or suspense.

He does not. His narrator – a younger version of himself, whose awareness predates his own birth (“That was enough cum to knock up an elephant!” his father announces at his conception) – is what narratologist James Phelan would call a non-judgemental reporter.

According to Phelan, narrators serve three basic functions. They can report on actions, events and phenomena, they can interpret actions, events and phenomena, and finally they can evaluate actions, events and phenomena.

Example: Mary Shelley sent Lenore Blaine a warning letter (report). Mary Shelley sent Lenore Blaine a warning letter because she was missing her daughter Hannah and didn’t know how else to deal with these feelings (report + interpretation). Mary Shelley sent Lenore Blaine a warning letter because she was sad and frustrated, which only further proves what an unfit mother she is (report + interpretation + evaluation).

The downside of Blaine’s reportorial schema, rarely rising to the level of interpreter and basically never casting judgement on anyone, is that it causes the prose to become rhythmically and tonally repetitive at times. The following is a pretty standard paragraph, which demonstrates that in the eyes of God, all sentences are created equal:

The celebrant pronounced them husband and wife. Tom kissed Lenore with an enthusiastic amount of tongue. The crowd cheered. A jukebox blasted the opening riff of “You Shook Me All Night Long” by AC/DC. Beer flowed from a keg. Grease wafted from a barbecue. Lenore threw a bouquet over her shoulder.

Subject verb object. It may be the syntactical cornerstone of the language, but even stonemasons permit themselves to show off with the odd ornamental relief from time to time.

While somewhat lacking in subtext, the upside to Blaine’s no-frills prose is that the 360-odd pages offer up a lightning-quick read. Chapters are broken into small vignettes that allow the author to keep all of the characters and subplots on the go at once. And, when all is said and done, I felt warmed by a human connection, for which style is more often than not only a cheap substitution, anyway.

A bloody good yarn

At the heart of this book lies, well, a whole lotta heart. Lech Blaine’s family love one another ferociously. And although the Shelleys’ omnipresence warps the narrative’s chronology with all the weight of a black hole, it’s the glowing light of the Blaines’ expansive love that keeps the story from folding in on itself.

On more than one occasion, the family recollections reminded me of some mildly adultified episode of Bluey (high praise indeed!). Take Christmas Day of 1999, when brothers Steven and John buy their mum a Mexican walking fish that eats all the other fish in the fishbowl before morning, and Dad follows up with a bottle of Joop:

“Joop is a man’s cologne, Thomas,” said Mum.

Dad had been hoodwinked by the pink packaging.

“Shit,” he said. “Ya kiddin’ me?”

“I kid you not,” she said.

Dad tested the Joop on his neck and wrists and enjoyed the scent. From that moment onwards, he exclusively wore Joop.

Just goes to show, you can take the man out of Paris, but you can’t take Parisian haute couture out of the man!

And then there’s the day Tom and Lenore are first introduced to Michael Shelley by way of photograph:

“What is the go with this bloke?” [Tom] asked.

“He’s a narcissist,” said Lenore.

“An arsonist?” asked Tom, alarmed.

“No, Thomas. A narcissist. He loves himself.”

Tom was relieved. He nodded, knowingly.

“So, he sniffs his own farts?” he asked.

“Something like that,” she said.

These are salt-of-the-earth people, and it’s hard not to be won over by their affection for one another and willingness to do right by their fellow creatures.

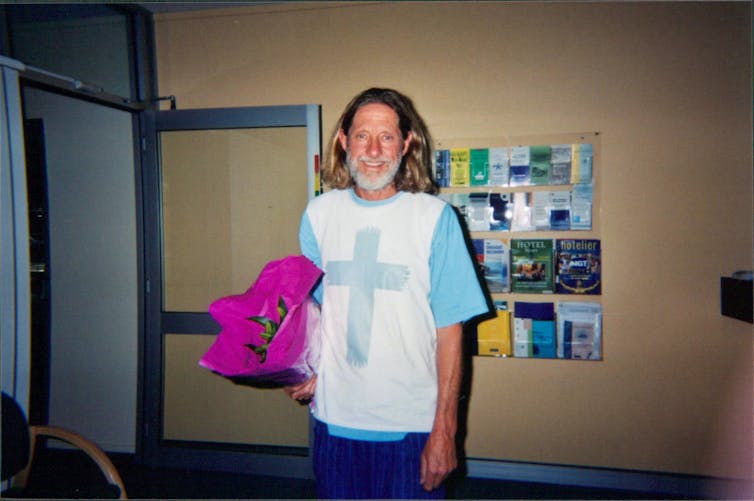

I don’t think it’s ruining anything (and, if a recent Good Weekend promotional piece is anything to go by, neither does the author) to report that the Shelleys have both since passed away – Michael dying in his sleep in 2017 and Mary shortly after. As have Blaine’s parents: Tom in 2011 and Lenore in 2018. “That is handsome news,” whispered Lenore when she heard of Michael’s passing.

Speaking of promotional pieces, the prologue makes mention of an interview the author did with Richard Fidler on his ABC radio program, Conversations, back in 2017. Over the course of an hour, the two of them “chatted about life, death, love, grief, rugby league, the foster care system in Queensland and how all of these subjects relate to [Blaine’s] unique family”.

If you’re unsure whether you should read this book, click on the link above and take a listen for yourself. The author speaks like he writes, without pretence or judgement. Like a man with a “yarn to spin”. And a bloody good one at that.

Luke Johnson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.