If you close your eyes and imagine a system of planets orbiting a distant star, what do you see?

For most people, such thoughts conjure up systems that mirror the Solar System: planets orbiting a host star on near-circular orbits – rocky planets closer in, and giants such as Jupiter in the icy depths.

However, the more we study the cosmos, the more we begin to realise planetary systems like our own might be more of an exception than a rule.

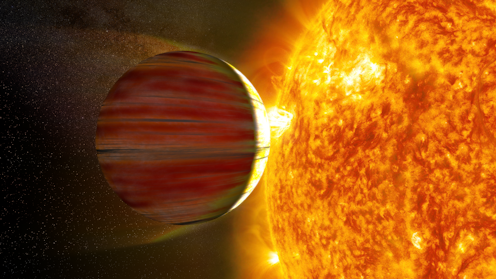

Imagine a system with one gaseous planet, a little larger than Saturn, skimming the surface of its host star on an extremely fast orbit. It’s hellishly hot and glows a dull red, baking in stellar radiation.

Then imagine another giant planet farther out, larger than Jupiter, moving on a distant and highly elongated orbit which makes it look more like a comet than a traditional planet.

It doesn’t sound much like home, does it? Yet that’s what we found.

Introducing the HD83443 planetary system

The story of the HD83443 system begins in the late 20th century, when astronomers began obsessively observing stars similar to the Sun. They were looking for evidence of those stars wobbling back and forth under the influence of unseen planetary companions.

Using the 3.9 metre Anglo-Australian Telescope at the Siding Spring Observatory near Coonabarabran, researchers discovered a planet orbiting the star HD83443. This planet, HD83443b, was as massive as the gas giants Saturn and Jupiter.

But that’s where the similarities ended. HD83443b is a “hot Jupiter”: a giant gas planet skimming the surface of its host star (which is a little smaller and cooler than the Sun), and completing each lap in less than three Earth days!

For two decades since its discovery, we have continued to monitor the HD83443’s movements. In recent years, we’ve been conducting this work at the University of Southern Queensland’s Mt Kent Observatory.

By combining our observations with others, we discovered a strange new planet in the system, which we describe in a paper published last month.

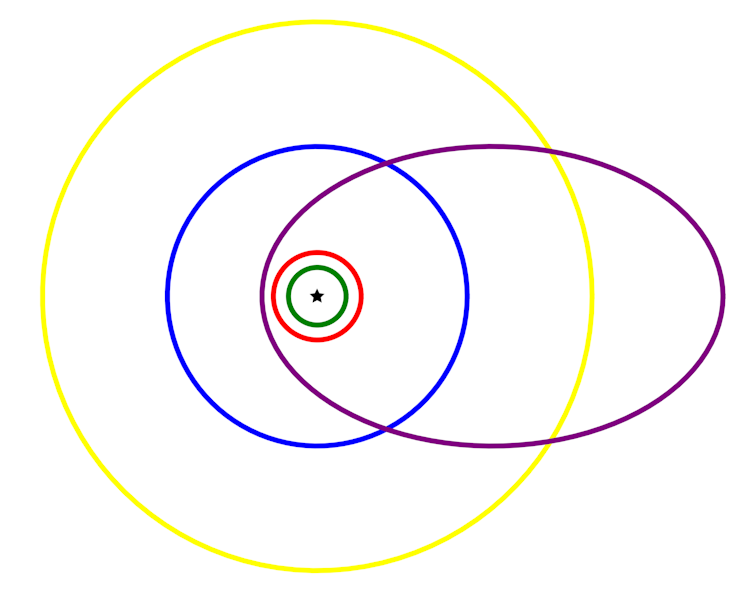

This world, HD83443c, takes more than 22 years to orbit its host star, and is some 200 times more distant than its hellish sibling. Since HD83443c’s “year” is so long, we needed more than two decades of observations to confirm its existence – by tracking a single lap around its host star.

But what’s really unusual is the eccentricity of its orbit. While the planets in the Solar System follow near-circular orbits, HD83443c follows a much more elongated path reminiscent of comets in our Solar System.

The aftermath of a planetary tango

Planets such as the “hot Jupiter”, HD83443b, are particularly interesting to astronomers as they’re unlike anything close to home. Gas giants such as Jupiter begin their lives far from their host star where ices are abundant.

Those ices allow them to rapidly grow, gaining enough mass to shroud themselves in huge atmospheres.

Unlike the Solar System’s giant planets, as HD83443b grew to maturity, it must have migrated inwards to end up close to its host star. What caused this migration?

Well, over the years, astronomers have found many hot Jupiters. In trying to understand those weird planets, several mechanisms have been proposed to explain their migration – but in most cases, any evidence of the cause of the migration is lost in the distant past.

In the specific case of HD83443b, however, it seems our new discovery might have provided the evidence of the smoking gun. The newly-discovered world, HD83443c, might be the reason its sibling ended up on its current hellish orbit.

Imagine HD83443c and HD83443b first forming in the icy depths of the HD83443 system. They would have been buried in the massive disc of gas and dust surrounding the star, called a “protoplanetary disk”.

As the planets moved through the disc, they fed from it, growing ever more massive, and drifting slowly inward as they interact with the disc around them.

Eventually they came too close together. They didn’t quite collide, but as they swung past one another, their immense gravitational pulls acted like a slingshot, catapulting them both onto new orbits.

HD83443b, the hot Jupiter, was flung inwards onto an orbit that skims the star’s surface at its closest approach, before swinging back outwards towards the initial scene of near collision. The other planet, HD83443c, is flung outwards onto its current elongated path.

Over millennia, something remarkable happened. Every time HD83443b swung close to its host star, its presence raised tides on the star, and in turn the host star caused tides to rise on it. This would have essentially “applied the brakes” to HD83443b’s motion.

This means HD83443b lost a tiny bit of speed each time it swung past the host star. As it flew back outwards again, it failed to travel as far as before and its orbit was slowly circularised. It was dragged inwards until it reached its current tiny, circular orbit – on which it will spend the rest of its life.

HD83443c, however, experienced no such fate. After having been flung outwards during the initial encounter with HD83443b, it remained so distant from the central star that its orbit was never impacted.

Its very slow and elongated orbit is evidence of that initial planetary encounter from when the system was young.

Is there no place like home?

This story is a fascinating one – but the main goal of our ongoing search for alien worlds is to find places much more like home.

We’re using the same tools that led us to HD83443c to find planetary systems like our own – with giant planets on orbits far from their host stars. We may need to gaze out at distance stars for decades at a time, watching their graceful celestial waltz.

We will no doubt find many more surprising systems akin to HD83443, that reveal more about the true variety of planetary systems out there.

Brad Carter receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Jonti Horner received funding from the Australian Research Council in 2016 to help construct Minerva-Australis, the exoplanet detection array at the University of Southern Queensland that was used to detect HD83443 c.

Adriana Errico does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.