It seems hardly a day goes by without another report of a cyber crime incident. With Medibank still fresh in our minds, the latest attack is on a Sydney-based cancer treatment facility, Crown Princess Mary Cancer Centre in Westmead Hospital.

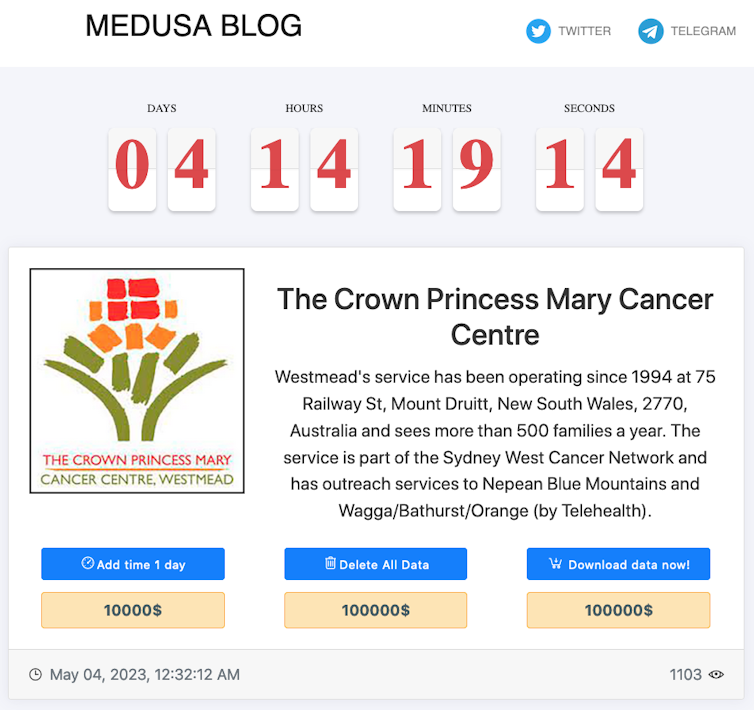

The cyber criminal group Medusa claims to have stolen thousands of files and is holding them to ransom.

In what has become a common practice, the criminal gang seems to be using double extortion. In such scenarios, criminals typically demand a fee to “release” the data back to the organisation – often with a “sample” made available to verify their claims.

The gangs then double-down with threats to publicise the data via their websites if payment isn’t made – in this case, a deadline of seven days.

Medusa is offering a range of options to delay the public release of data by 24 hours (US$10,000), to download and/or delete the data from the gang for US$100,000.

It’s currently unclear what will happen on Friday morning if the ransom is not paid. However, the Medusa Blog offers free access to data stolen from previous victims who did not pay the ransom by the deadline.

According to CyberCX, Medusa is the “second-most active cyber extortion group in the Pacific”. Medusa has been trying to compromise organisations in Australia and New Zealand since the beginning of 2023.

Read more: Why are there so many data breaches? A growing industry of criminals is brokering in stolen data

Why target health services?

Any cyber attacks on the health sector are dangerous. While some cyber criminals have previously avoided schools and health-care organisations, it seems these are now fair game.

Knowing the services and data held by these organisations are critical, it’s not surprising to see so many ransomware attacks are launched against critical health-care infrastructure.

Some notable incidents targeting the Australian health systems have included Medibank, Melbourne Heart Group and Eastern Health which operates four hospitals in Melbourne’s east – an attack which resulted in elective surgeries needing to be postponed.

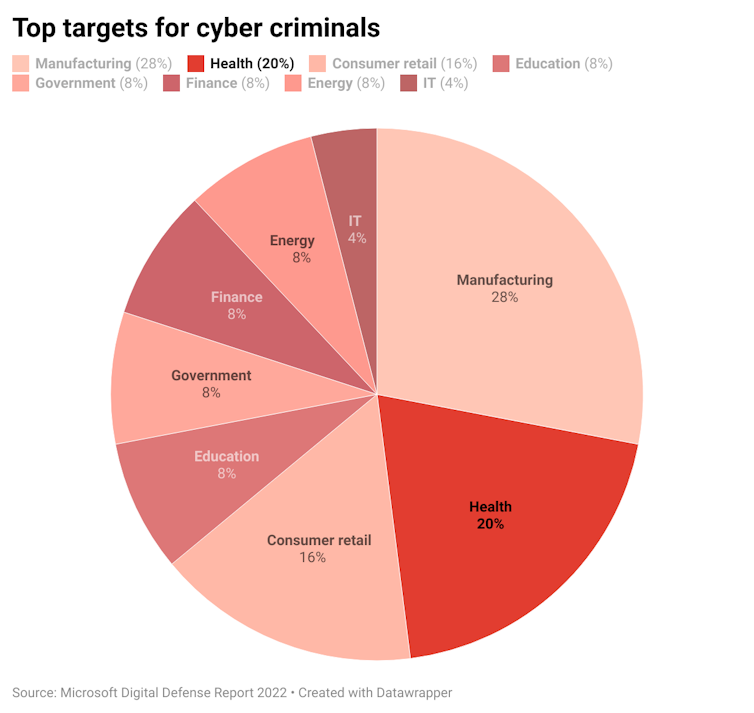

According to tech giant Microsoft, the health-care sector (and aligned industries) is one of the top targets for cyber criminals.

Read more: Australian hospitals are under constant cyber attack. The consequences could be deadly

What are the impacts?

The health sector deals with our most private data – none of us want this data in criminal hands. Apart from the privacy issues, the inability to continue regular activities in any health-care facility poses life-threatening risks.

A recent study showed from 2016-2021, US health-care providers experienced 374 ransomware attacks that exposed the private health information of nearly 42 million patients.

Nearly half of these ransomware attacks disrupted the health-care services, with impacts including electronic system downtime, cancellations of scheduled care, and ambulance diversions.

Why do they keep happening?

Technical advances in the health industries have undoubtedly improved treatment and overall patient care. While this growth in technology is a positive for health care, it exposes health systems to cyber criminals.

With each passing year there is increased connectivity between clinical systems and medical devices. The health-care sector needs to be more staffed and heavily reliant on internet-connected systems also known as digital health. This inter-connectivity makes health systems more complex and harder to secure.

With the exception of state-sponsored groups, cyber criminals are primarily motivated by financial gain. Health care is undoubtedly one of the most promising targets as, if compromised, the organisations are more likely to pay the ransom – ultimately, because lives are at stake.

Cyber criminals capitalise on this and, even after good governance and enhanced cybersecurity within the sector, these incidents are likely to continue.

Living with cyber criminals around us

So far, reports about the Cancer Centre at Westmead have not indicated that operations have been significantly impacted. This may imply no computing devices have actually been compromised and locked – this could be seen as a positive.

However, those who have examined the samples of data published on the Medusa Blog have suggested it seems genuine.

As Robert Mueller, former Director of the FBI, famously said:

There are only two types of companies: those that have been hacked and those that will be hacked.

Cyber crime has become a global industry with estimates predicting the impact at more than US$8 trillion in 2023. With such potentially lucrative benefits, we have to accept we will be sharing cyberspace with criminals for the foreseeable future.

There are, of course, actions that can improve our cybersecurity preparedness, regardless of the sector. While nothing will completely eliminate the risk, making ourselves a less attractive target helps to reduce the likelihood of being a victim. So it’s important to:

- protect your systems: apply patches to all devices (including mobile phones); educate users to segregate personal and business activities; use strong and unique passwords for all systems/services

- include all systems: don’t forget the internet of things and operational technology (all the devices and software we use that connect to the internet); check default settings (changing any default passwords); and plan the disposal of old systems

- protect your data: data collected from all sources need to be kept in appropriate locations; think about how long you will keep data; and ensure data is protected from creation to destruction.

- protect your people: educate all staff on basic cyber hygiene; vet new staff; and think about your off-boarding practices

- seek advice: when things go wrong bring in the experts and liaise with law enforcement or other government agencies as appropriate.

And, finally, do not pay the ransom – it may be a difficult decision, but it only encourages the criminals behind the ransomware campaigns to keep going.

Read more: Medibank won't pay hackers ransom. Is it the right choice?

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.