He’ll go anywhere to bug a private conversation.

The above could easily be a newspaper headline from 1974, the year Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in disgrace after being caught on tape ordering a cover-up of the Watergate scandal two years earlier. Instead, it’s the tagline for The Conversation, a movie released that same year, which dealt directly with both the ethics of surveillance and the psychological fallout of paranoia.

Political scandals have existed since politics began, and since the birth of cinema itself, the silver screen has reflected these upheavals and the mistrust they cause. Decades before Watergate, we saw film noir play upon post-war disillusionment. Then the beckoning fear of communism throughout the 1950s wound its way firmly into the cinematic conversation, where movies like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), and Topaz (1969) transliterated the Red Scare into celluloid and blew it up onto the big screen. Throw in events like the 1963 assassination of JFK and the Chappaquiddick incident in 1969, and you already have a country increasingly distrustful of the narrative being fed to them.

But when Nixon’s administration covered up its involvement in the 1972 break-in at the Democratic National Committee’s offices — perpetrated by burglars paid via a secret slush fund operated by the president’s re-election campaign — a new cinematic catnip was born. It wasn’t a neighbor that was a potential secret Red agent, or a series of unsubstantiated claims about an assassination. Nixon got caught, he confessed, and he resigned.

It seemed, for the first time, that the lid had been lifted on the most powerful organization in the entire country. From that moment, the Watergate scandal had an enduring effect on the cinematic landscape that followed. Fifty years on, it boasts the legacy of being — of, possibly, all the events in American political history — the ripest for adaptation: rich with reveals, twists, and a lingering sense of dread.

“Conspiracies involving murder by federal agencies used to be found in obscure publications of the far left,” wrote film critic Roger Ebert in early 1975. “Now they're glossy entertainments starring Robert Redford and Faye Dunaway.” He didn’t seem too happy about this, even if he ultimately gave the movie in question — Three Days of the Condor, directed by Sydney Pollack — a positive review. “How soon we grow used to the most depressing possibilities about our government,” Ebert mused. “Hollywood stars used to play cowboys and generals. Now they're wiretappers and assassins, or targets.”

The movie, which saw Redford star as a bookish CIA researcher, follows a classic conspiracy formula. A small fry finds himself in over his head and is determined to rise above the big dogs to expose corruption. One of many conspiracy flicks of its kind in the mid-1970s, academics saw this deluge as an opportunity for audiences to synthesize their real-life anger at political organizations into something tangible, with such movies acting as “resolutions for inadequately explained socio-historical traumas.”

Many at the time, however, saw these movies as toothless attempts to emulate the level of corruption happening in real life, unable to coalesce the economic imperatives of studio filmmaking with a genuine political message. In a 1976 pan of Condor, Patrick McGilligan decried it as “evasive, exploitative and politically vacuous.” If you look at how the plot is beefed up with a dicey Faye Dunaway romance/kidnap subplot, you can see where he’s coming from here.

While today it’s considered a masterpiece, Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View similarly failed to escape criticism. The movie starred box-office mainstay Warren Beatty as a television journalist who becomes aware of a secret organization that recruits political assassins and kills off witnesses. The Senate hearings for Watergate were in full swing during production, and members of the cast and crew would sneak off to Beatty’s trailer to watch proceedings unfold during downtime. Sure, the book the screenplay was based on was unmistakably tied to JFK trutherism, but the entire thing whiffs of Watergate jitters.

Writing in The New York Times in 1974, just three days after Nixon’s resignation, Stephen Farber disparaged the upward tick in political conspiracy movies. He criticized Parallax as “probably the most mindless and irresponsible of the lot [...] exemplifying the emptyheaded, fence-straddling approach to controversial issues that has made Hollywood's political movies such a joke.” He continued: “Today's mass audience wants to believe in omnipotent, omniscient, indestructible conspiracies.”

Two years later, Pakula would direct the definitive Watergate flick, All The President’s Men. The two films (which complete his “paranoia” trilogy, alongside 1971’s excellent Klute) differ starkly in their degree of optimism. In one ending, Nixon resigns as Washington Post journalists Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward triumphantly type up their exposé. In the other, a government apparatchik says with chilling, deceptive finality, “There is no evidence of a conspiracy.”

But both were equally astute in how the very fabric of the filmmaking makes us feel. The jarring split diopter shots in All The President’s Men force us to discount no detail, to keep an unnaturally sharp eye on the figures that operate in our periphery. In Parallax, Pakula shot his characters at a long distance, giving the effect of a sniper tracking their movement, drowning them in sparsely-populated frames that emphasized their isolation and smallness.

Some filmmakers peddling their paranoid wares distanced themselves from potential accusations of half-baked posturing by looking inward. It was certainly a stroke of perverse serendipity that Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation was written before the 1972 break-in ever occurred because it is inadvertently one of the most sophisticated and striking films about Watergate-era paranoia to come out of that decade.

“How soon we grow used to the most depressing possibilities about our government.”

“When Watergate happened,” Coppola says in a May 1974 Filmmakers Newsletter interview with Brian De Palma, “I was really frightened that people would expect it to be about spies and tapes and that sort of thing, and then be very angry that it wasn't. Right from the beginning, I wanted it to be something personal, not political, because somehow that is even more terrible to me.”

The film’s famous opening, voyeuristically surveying a crowd in San Francisco’s Union Square, cinematizes the paranoia of the time — relaying the intense feeling of an invasion of privacy. Gene Hackman’s Harry Caul, a surveillance expert, is wracked with guilt over his role in a wiretapping sting that went wrong. Drawn into a new investigation entirely conducted through the manipulation of audiotapes, the film is a chilling examination of the effects paranoid conspiracies have on our lives, shaping us into individuals who are unable to trust.

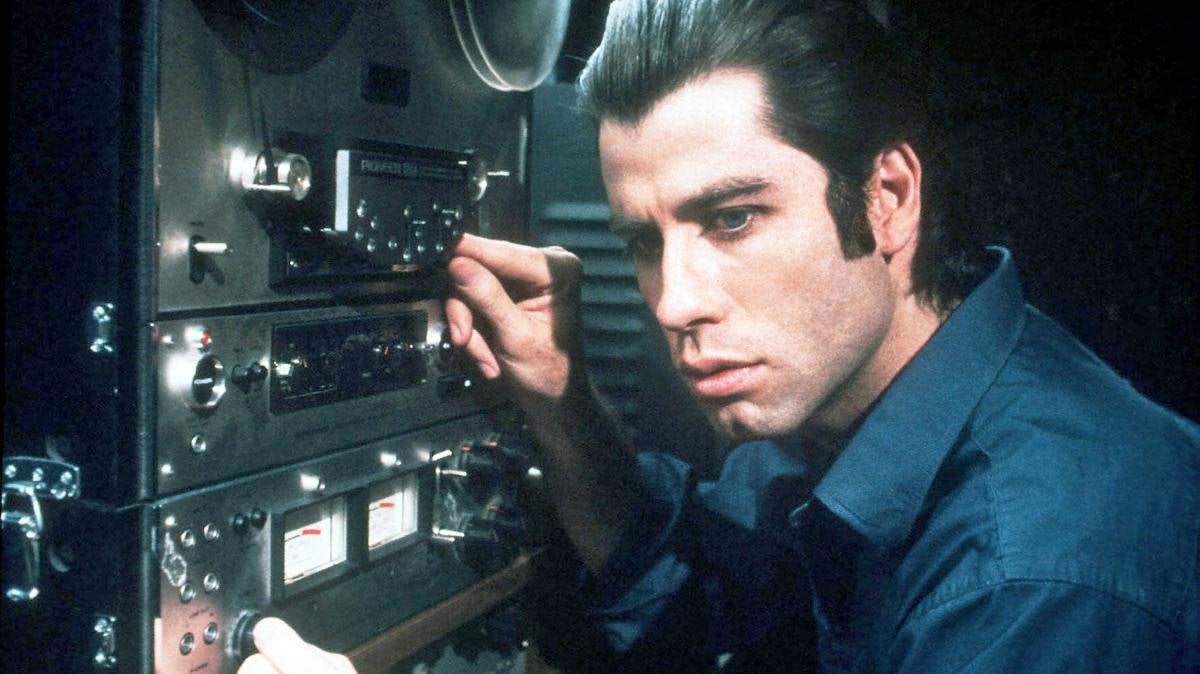

“Nobody wants to know about a conspiracy,” John Travolta’s sound engineer character Jack explains, wide-eyed and frantic, in Brian De Palma’s 1981 paranoia thriller Blow Out. “I don’t get it.” His character is also sucked into a political cover-up that plays out in a multimedia hall of mirrors: television, telephones, photographs, wiretapping, dubbing. When he thinks that he has inadvertently recorded a murder, the audio trickery — like that in The Conversation — instantly would have reminded contemporary audiences of that final nail in Nixon’s smarmy coffin: the “smoking gun” tape that proved, unequivocally, that the president had lied to the public about his involvement in the Watergate whitewash.

Blow Out uses the blue and red tones of the star-spangled banner as color motifs throughout, and the film’s finale, a tragedy that takes place at a jubilee celebration of Philadelphia’s liberty bell, is heavy irony for this so-called symbol of American justice. At its very heart, the movie epitomizes Nixonian anxiety.

While the conspiracy thriller was overtaken in popularity by legal thrillers and erotic thrillers in the ‘80s and ‘90s, dramatizations of the Watergate scandal and the players involved have continued at pace into the 21st century. In 2022, the first season of Slate’s popular podcast Slow Burn was adapted into a Starz series, Gaslit, starring Julia Roberts as significant Watergate figure Martha Mitchell. This fall will see the release of the miniseries The White House Plumbers, starring Woody Harrelson and Justin Theroux as puppeteers of the Watergate break-in: E. Howard Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, respectively.

So why, still, does Watergate remain an obsession?

Dan Mirvish, director of upcoming Watergate black comedy 18½ starring John Magaro and Willa Fitzgerald, was just 7 years old when the Senate hearings were on television. “It didn't matter how old you were,” he tells Inverse. “It was the only thing on TV because it was on every network, and there were only three or four networks at the time.”

This, he reckons, is a salient reason why the scandal remains so present in the cultural landscape: “It was a televised, visual scandal, and it lasted for two years. We saw Nixon say ‘I'm not a crook’ and walk off into his helicopter. This was really the final undoing of the trust that people had in authority, in government.”

18½, which releases June 3, is deeply aware of the scandal’s farcical nature. A piece of historical fiction, the movie reimagines what could have happened if those titular 18-and-a-half-minute-long tapes — the ones “accidentally” deleted by President Nixon’s secretary Rose Mary Woods — were not, in fact, lost. The hijinks that ensue feature hippies, spies, and deadpan humor. But most importantly, they reflect how and why Watergate is ripe for cinematic adaptation: the scandal’s audiovisual trickery, improbable twists, and dramatic, third-act reveal.

But political paranoia can’t quite hold the same power it did in the 1970s. People who ascribe to conspiracies today are often seen as either cultish QAnon edgelords or easily-duped Facebook auntie types that lack media literacy. Don’t we view “truthers” with an edge of pity, disdainful of their claims of enlightenment? Don’t we today, in the words of theorist Skip Willman, “deride [the] conspiracy theory as a compensatory fantasy that neatly orders the chaotic universe”?

When I pose this question to Mirvish, he surmises: “Depending on which conspiracy you happen to be on, the other side of the politics thinks you’re a conspiracy nut. It’s not even so much about left and right, it's about who's gullible and who will believe anything.”

“It’s not even so much about left and right.”

So where next for paranoia cinema? Will political conspiracy movies be left in the smug, self-congratulatory hands of director Adam McKay, or shoehorned into dull biopics of cabinet-rifling investigators? The answer is likely that political scandals, with their detail-oriented complexity, will predominantly play out in prestige television where audiences only need to synthesize information on an hourly basis instead of sustaining focus for a two-hour-plus movie. As such, it is set to follow the general trend of cinema becoming more escapist as opposed to challenging, for better or worse.

But what strikes us, when we revisit these masterclasses in a specific type of tension from the 1970s, is how starkly relevant they are to the political landscapes of today. By carefully building atmosphere, contemporary directors managed to incite dread and reflect the public mood in a way popular cinema today struggles to. No matter how complex or long-winded the scandal may have been — its details slowly eked out by dogged reporters over two long years — Watergate left an indelible mark on the film industry, on politics, and on our very relationship with governing forces.