How do you make the cosmic seem personal? When a film is dealing with matters of potentially galaxy-sized importance, it's imperative that it also grounds its story in recognizable, relatable emotions. Otherwise, you end up with a movie that is big but hollow. That may seem like an obvious problem to try to avoid, but many sci-fi films nonetheless fail to do so. There are only a small number of movies that succeed at that. Christopher Nolan's Interstellar is one. James Gray's Ad Astra is another.

The underrated sci-fi drama hit theaters in September 2019. A few months earlier, its star, Brad Pitt, gave a charismatic, eventually Oscar-winning supporting performance in Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Despite that fact, audiences largely ignored Ad Astra when it was released. While many prominent critics gave it positive reviews, plenty also undersold it. Five years later, its place on the list of Hollywood's best contemporary sci-fi dramas seems undeniable.

It's a space-set blockbuster that doesn't preach the value of either cosmic expeditions or constant technological advancements. Instead, Ad Astra asks a far more subversive and unfortunately timely question: What do we lose when we prioritize exploration over everything else?

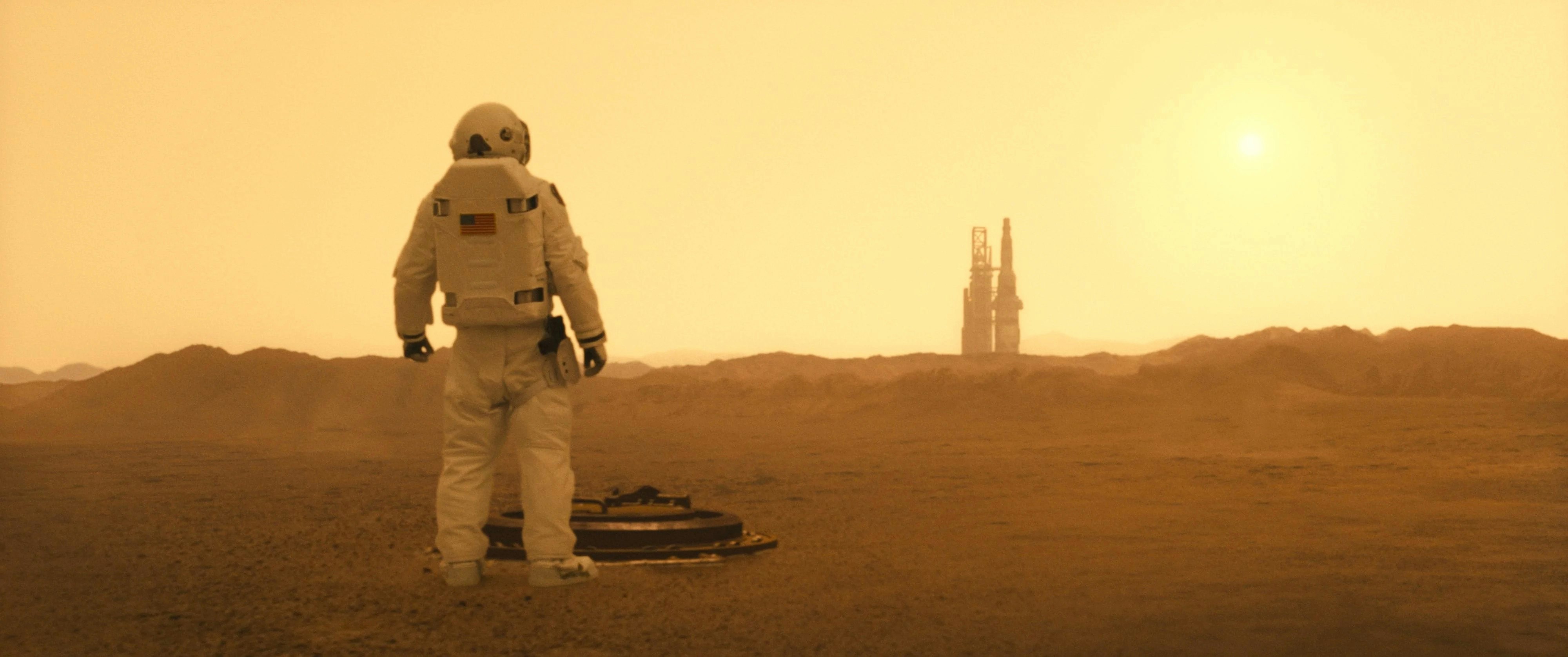

Ad Astra takes place in the early 22nd century. It follows Roy McBride (Pitt), an astronaut who has trained himself to tamp down his own emotions in order to pull off on his often dangerous missions for the U.S. government's SpaceCom. This training, itself a survival mechanism, is the source of an emotional rift between Roy and his wife, Eve (Liv Tyler), that haunts him throughout Ad Astra. His strained relationship with his father, H. Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), similarly hangs over him like a shadow for much of the film. Roy gets the chance to finally address his estrangement from his father, though, when he is assigned by SpaceCom to travel across the stars and try to make contact with him.

Clifford left Earth 29 years prior to command a space station called the Lima Project that was sent to scan for any signs of other, potentially intelligent life in the universe. However, we’re informed in Ad Astra’s first act that those onboard the Lima Project have recently ceased all communication with their superiors on Earth. It is, therefore, Roy's mission to determine whether or not this interruption in contact has anything to do with a recent, catastrophic power surge that has rippled through space. If he succeeds, Roy may also get the chance to ask his father all of the questions about his departure that have been plaguing him for nearly 30 years.

Heavily influenced by Apocalypse Now, Ad Astra follows Pitt's Roy as he travels from Earth first to the Moon, then to Mars, and finally to Neptune on a journey to reconnect with his father. Along the way, he comes up against a number of obstacles, including a thrillingly rendered rover attack by pirate colonists on the surface of the Moon and a temporary imprisonment on a soundproofed Mars base. However, none of the hurdles that Roy encounters cause him as much trouble as his own emotional shortcomings.

The closer he gets to speaking with his father again, the more Roy begins to discern the cold emptiness of not only space, but also the very infrastructure that has been built around cosmic exploration. It is one defined by twisty bureaucratic oversight and corporate interests. While SpaceCom wants Roy to mute his own emotions so that he can be an effective astronaut, the organization also jumps at the first opportunity it can to capitalize on his relationship with his father. When it then deems Roy's involvement no longer necessary, SpaceCom tries to sideline and punish him for becoming emotionally invested in reconnecting with his father.

It is a maddening cycle that — similar to how the events of Apocalypse Now disturb and numb Martin Sheen's Willard — disillusions Roy to the work-first life he's long embraced. Indeed, in Ad Astra's quiet, mournful climax, he sees firsthand just how destructive a life of "infinite work" and endless scientific advancement can be. Clifford’s decision to put his own scientific pursuits ahead of his family leaves him a bitter shell of a human being. He, consequently, teaches his son an important lesson — namely, that a life spent away from Earth is destined to be an unfulfilling one. The further we push ourselves from the humanity that defines us, the lonelier and emptier we become.

Right now, it seems like every powerful corporation in our real world is in the midst of dissolving the very things that have helped define and sustain human life for centuries. There seems to be very little thought being dedicated on a global scale to the things we risk losing if we continue pushing forward at a pace that seems increasingly unsustainable and ill-considered. What will we lose if we continue to promote computer-generated "art" over things actually made by human beings? What will we lose if continue to invest more time in our virtual worlds than the one beneath our feet?

These questions are quietly at the center of Ad Astra, and they resonate even more now than they did in 2019. Few movies, in fact, explore quite as powerfully the toll the emotional detachment that is being demanded of all of us in the name of so-called "progress” takes. Rather than losing itself in a spiral of nihilism and hopelessness, though, Ad Astra finds room for hope at the end of its long, cosmic journey. In doing so, the film ultimately argues that it is never too late to find our humanity again — even if it sometimes takes walking up to the very edge of the abyss to realize when it’s time to turn back.