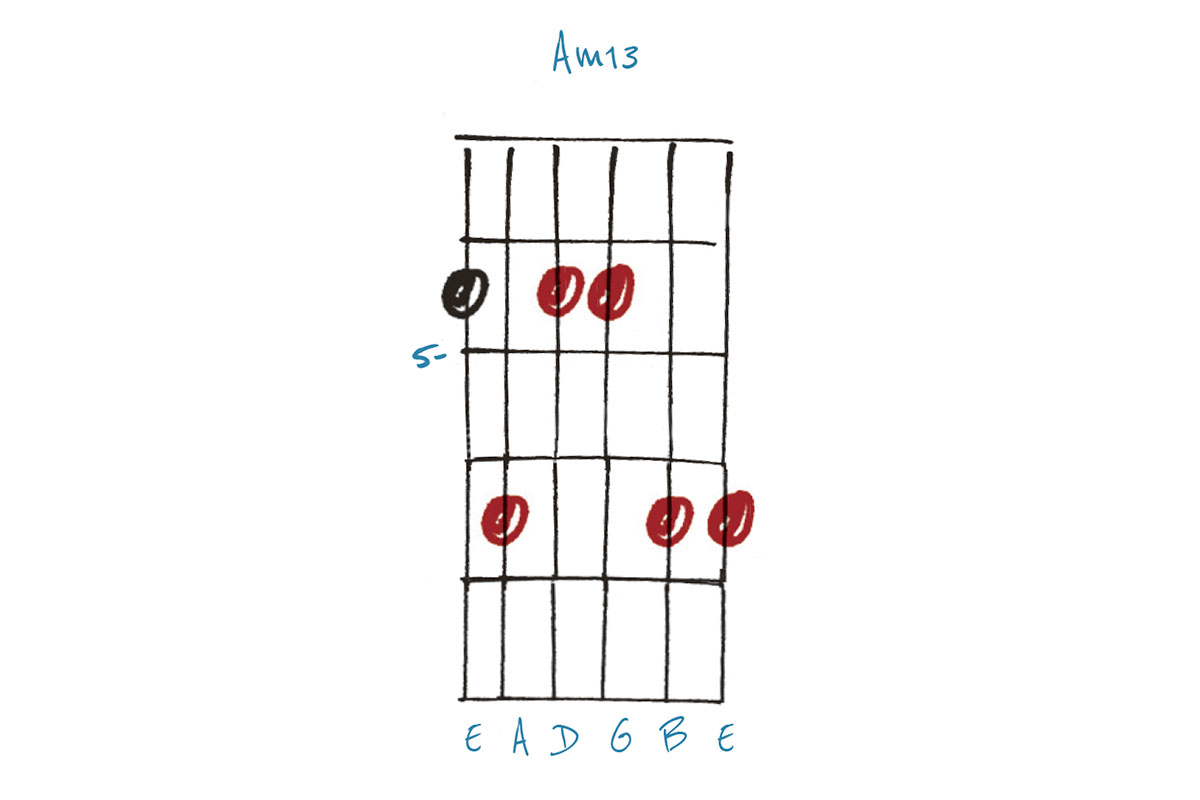

When rock ’n’ roll was being invented, the guitars used were often the hollowbodies that were originally designed for jazz – just check out early photos of Scotty Moore, Chuck Berry and, of course, Eddie Cochran.

In many cases, the harmonic sophistication of jazz found its way into some guitar parts and solos, too, which you’ll hear on the early Elvis recordings, plus Bill Haley’s Rock Around The Clock. Brian Setzer is a great example of a more contemporary player who clearly has a good knowledge of his jazz voicings, as evidenced on Stray Cat Strut or his version of Route 66 with The Brian Setzer Orchestra.

We’re not getting quite that complicated here, but these voicings certainly give you some nice options. While they don’t have to be exclusively ‘ending’ chords, this is a fun way to incorporate them into your vocabulary.

As ever, close attention to their content can also give ideas for single-note lines or patterns where you might rake across a chord/triad as part of a solo.

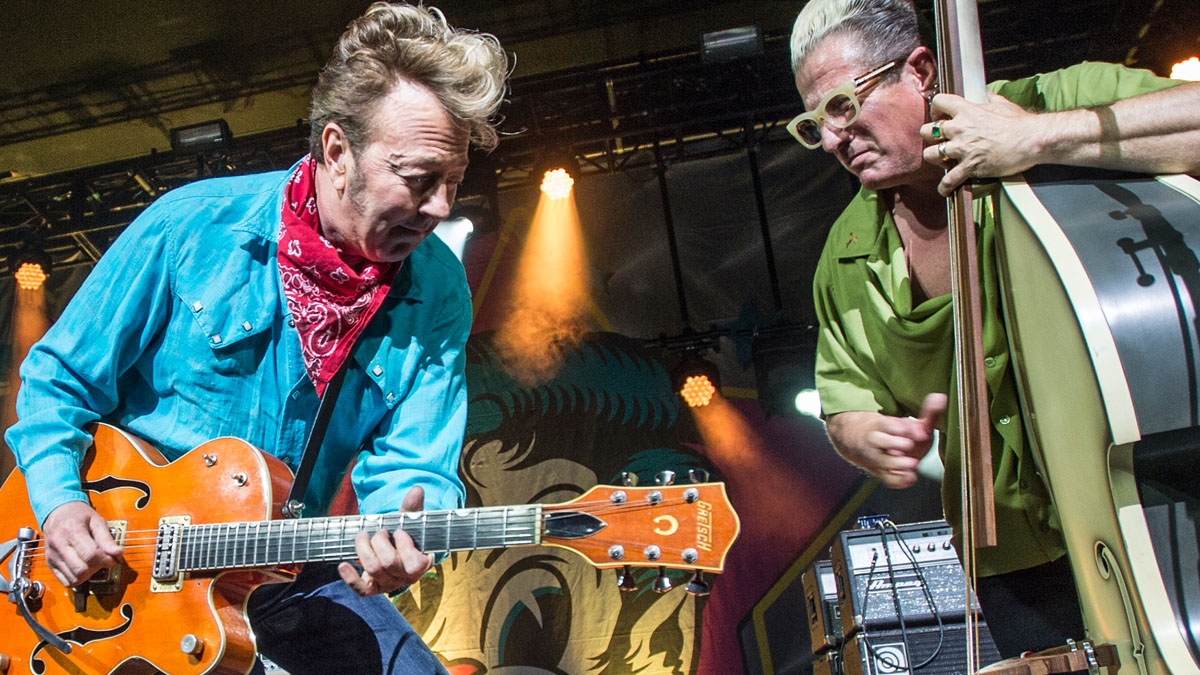

Example 1. Em6/9

This Em6/9 is so called because is contains the 6th (C#) and the 9th (F#). If only chord extensions could always be this simple! Actually, some may wish to call this Em6(add9). This would technically be correct, as there is no 7th, but you’ll find most chord charts will abbreviate where possible.

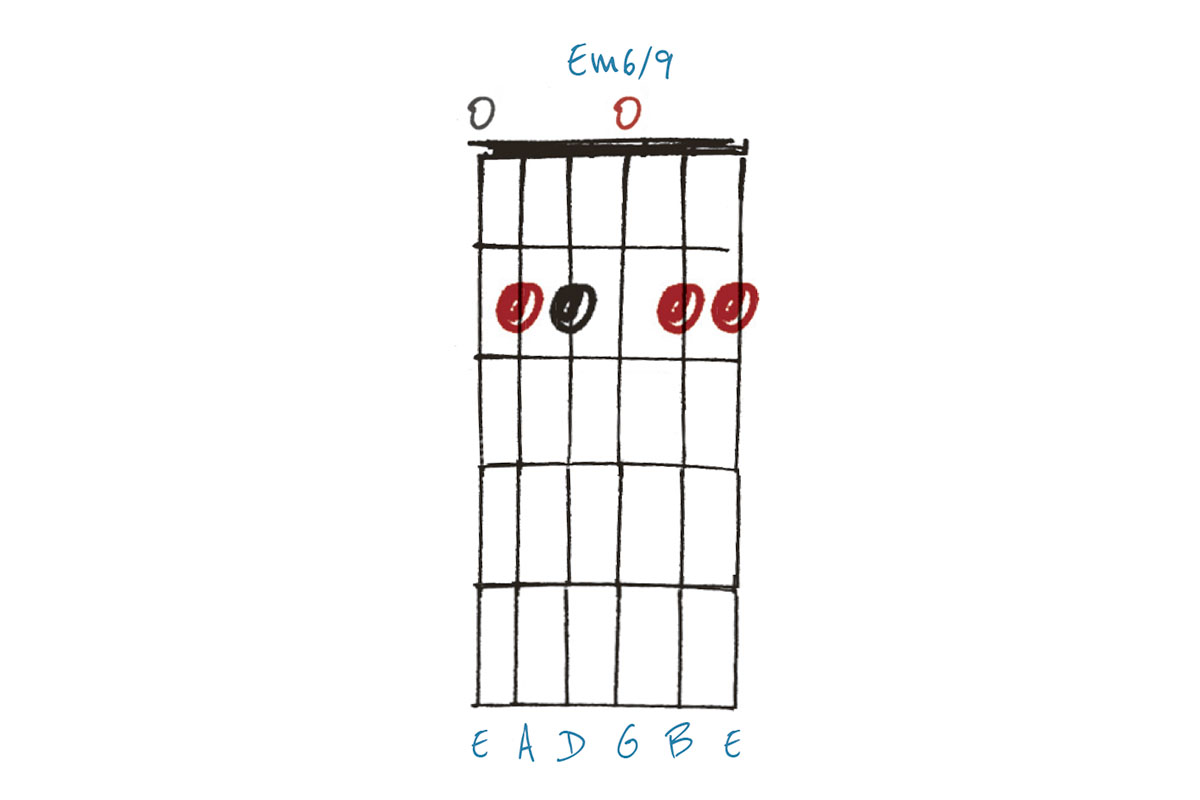

Example 2. Emaj9

This Emaj9 is, of course, a major chord, courtesy of the G# that appears on the fourth string. But the ‘maj’ part of the name actually refers to the major 7th (D#), which appears on the third string. Generally, chords are presumed to be major unless stated otherwise.

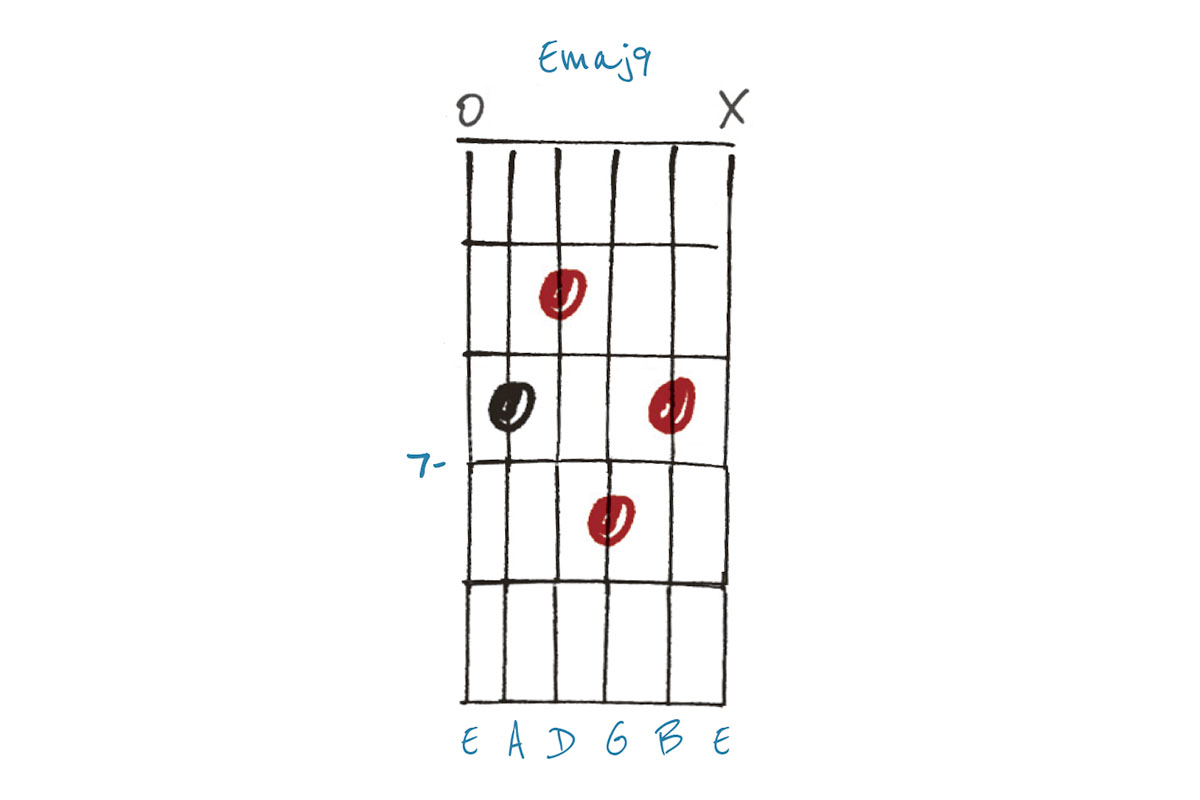

Example 3. Am13

This Am13 is a handful – and takes some explaining. It’s very similar in structure to Ex 1’s chord, but you’ll find a G, the dominant (or flat) 7th on the fourth string. This means we should see the F# on the second string as the 13th (not the 6th), and the 9th (B) on the first string is now a default part of the 13th chord, rather than needing to be specified!

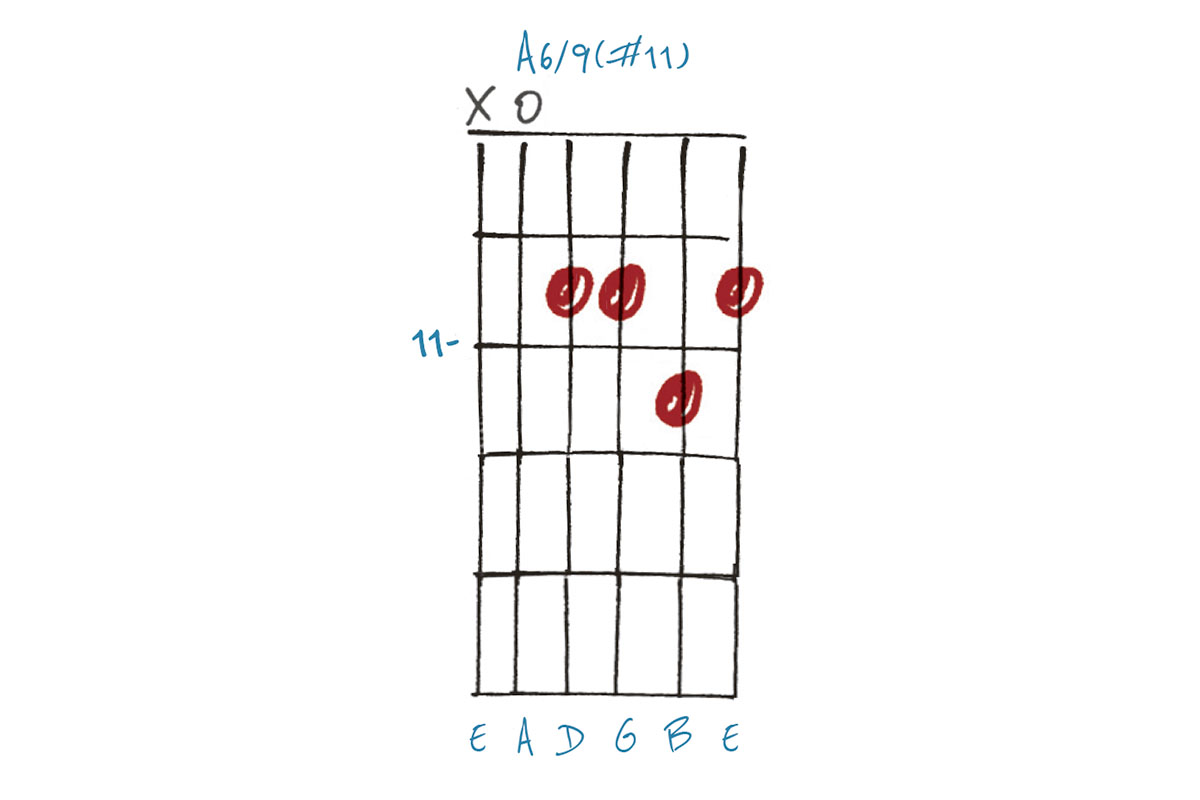

Example 4. A6/9(#11)

This A6/9(#11) uses the open fifth string as its root; you can omit this to play it in any other key. There is no dominant 7th and yet we have referred to the #11 (on the first string), which would normally require that… This convention avoids having to say A6b5add9, which suggests a very different voicing/feel with the b5 buried in the chord.

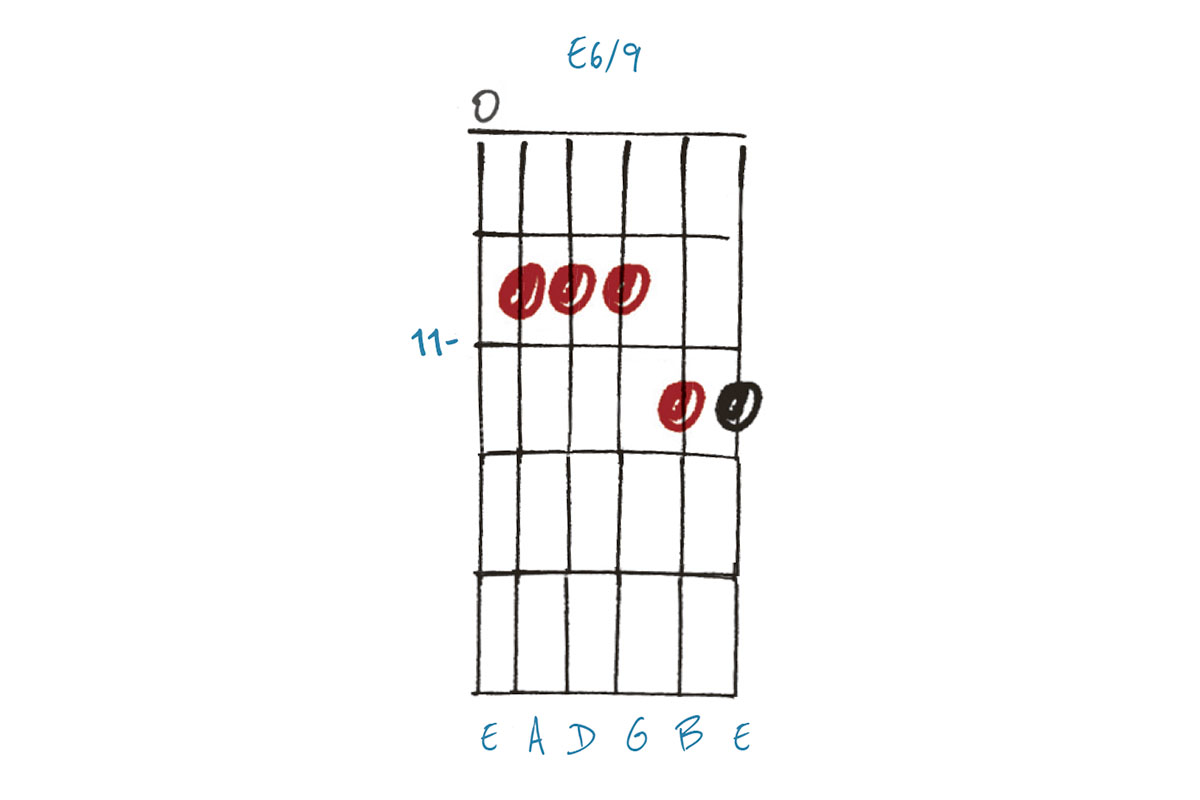

Example 5. E6/9

One of the nicest ending chords of all, this E6/9 is also short for E6(add9), but it’s worth knowing this abbreviated name. You could use the 11th fret of the first string (instead of the 12th shown here) to incorporate a maj7th. The abbreviated name for this would be Emaj69.