Two out of two Blade Runner films are box office bombs. But the key difference between Blade Runner (1982) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017) is that one received mostly positive reviews upon release. It was not the first one. Unlike its recent successor, Blade Runner not only failed to sell enough tickets to justify its existence but was also drubbed by critics. 40 years later, it's a sci-fi classic that brought an entire subgenre to the mainstream. What changed?

Blade Runner’s story is pure sci-fi noir. Ex-cop Deckard (Harrison Ford) is charged with hunting down artificial humans called Replicants, only to realize he’s in love with a Replicant named Rachael (Sean Young). As Deckard closes in on his prey, he reflects on his own humanity and stares into the middle distance long enough to make us wonder if he too is a Replicant. In what is now considered the definitive “final cut” of Blade Runner, that’s all but confirmed. Deckard, it appears, has had memories and dreams implanted in his mind, making him and Rachael the same and rendering his entire reason for hunting and “retiring” the supposedly soulless Replicants questionable.

Sounds awesome, right? But because of its style, and perhaps stiff competition from ET and The Wrath of Khan, Blade Runner suffered the twin curses of poor box office returns and bad press. According to Paul M. Sammon’s book Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner, the film made 14 million against a budget of 28 million. And although not all reviews were bad, most were, including legendary critic Pauline Kael writing this for the New Yorker:

“Blade Runner doesn’t engage you directly; it forces passivity on you. It sets you down in this lopsided maze of a city, with its post-human feeling, and keeps you persuaded that something bad is about to happen. Some of the scenes seem to have six subtexts but no text, and no context, either.”

Although this critique is savage, what’s hidden in Kael’s negative assessment is the key to why Blade Runner survived. Despite having an intriguing story, despite asking big questions about the human condition, and despite wonderful performances from Harrison Ford, Sean Young, Rutger Hauer, and Edward James Olmos, the movie works because of its style.

Blade Runner is all aesthetics, and the influence of those aesthetics is how it survived all these years to enter the mainstream. In the end, it didn’t really matter that only a fraction of the population had seen it. Arguably, relative to other big sci-fi movies, that is still true. You’re still far more likely to find someone who has never seen Blade Runner than someone who has never seen Star Wars. And yet the trappings of the cyberpunk genre are more pervasive in real life than the aesthetics of 2001 or A New Hope.

Speaking to The Paris Review in 2011, cyberpunk novelist William Gibson said:

“I was afraid to watch Blade Runner in the theater because I was afraid the movie would be better than what I myself had been able to imagine. In a way, I was right to be afraid, because even the first few minutes were better. Later, I noticed that it was a total box-office flop, in first theatrical release. That worried me, too. I thought, Uh-oh. [Ridley Scott] got it right and nobody cares! Over a few years, though, I started to see that in some weird way it was the most influential film of my lifetime, up to that point. It affected the way people dressed, it affected the way people decorated nightclubs. Architects started building office buildings that you could tell they had seen in Blade Runner. It had had an astonishingly broad aesthetic impact on the world.

Gibson, of course, is famous for many sci-fi novels, but specifically for Neuromancer, a novel published two years after Blade Runner hit theaters. The world Gibson creates is very reminiscent of Blade Runner despite the fact that Gibson had started writing it before its release, and the fact that Blade Runner is based on a 1968 Philip K. Dick novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, which doesn’t really contain any of the cyberpunk aesthetics.

Neuromancer is sometimes credited as the novel that began cyberpunk. Ditto Blade Runner, but for films. Essentially, prior to Neuromancer and Blade Runner, seeing this kind of urban-focused, dirty techno future wasn’t common in science fiction. Or, if it was, it lacked style. Gibson and Ridley Scott were aesthetic pioneers within science fiction which, in terms of impact, is only second to the storytelling.

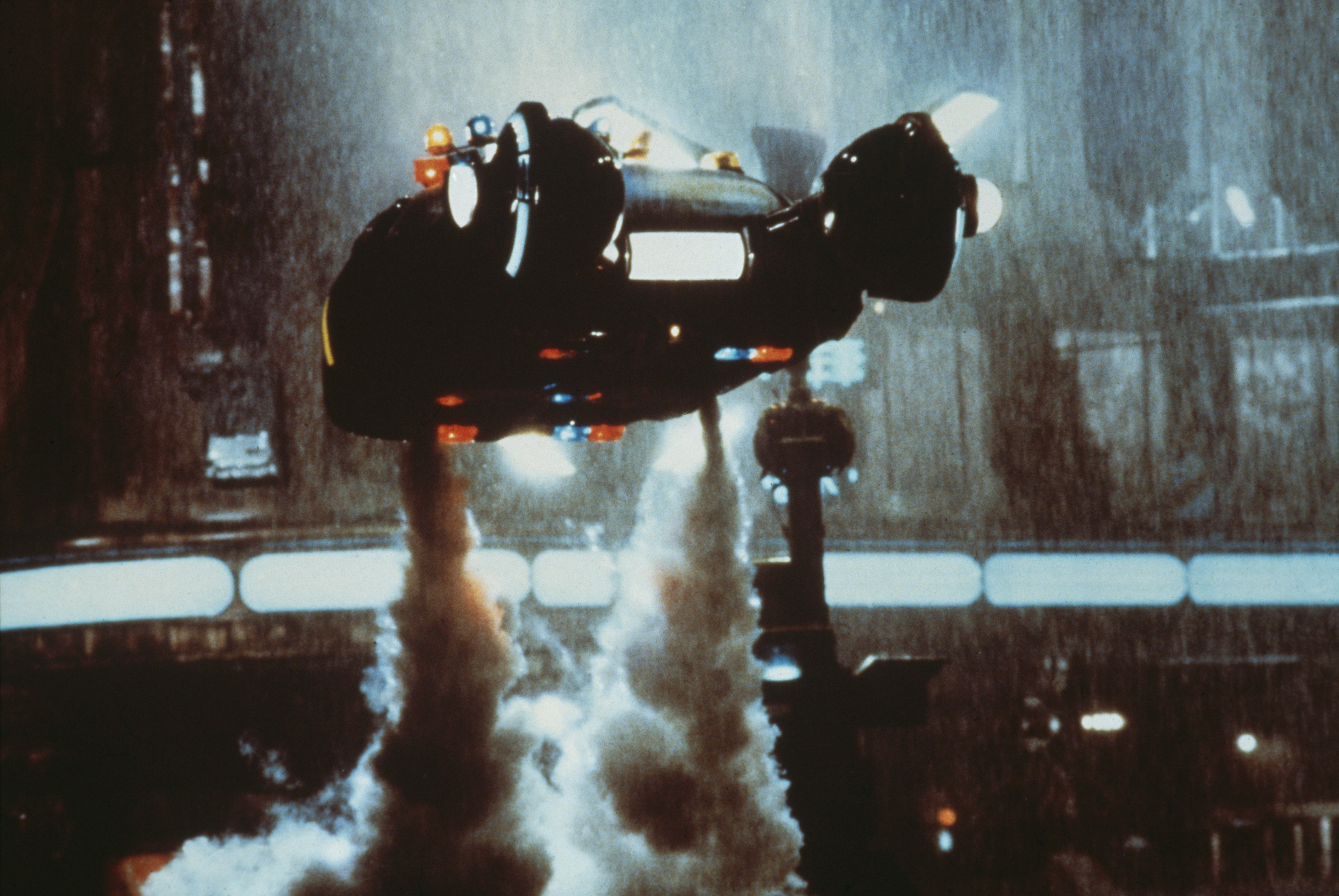

Much of the production design of Blade Runner can be credited to designer Lawrence G. Paull and legendary futurist Syd Mead. But Scott himself hand-drew sketches of many of the basic concepts for what we would see in the film. Both he and Gibson were world-builders just as much as they were storytellers. Writing teachers like to say the characters are the story. For Blade Runner, the characters are the story, but the environment, the city, is a character too.

Within the world of science fiction, it's easy to see how Blade Runner’s aesthetics changed everything. From The 5th Element to The Matrix, to quieter films like Ex Machina and almost everything about Black Mirror, what Blade Runner did was create science fiction shorthand. A dreary, tired future, one that felt familiar and made you long for being depressed about hard rain and robot romance. Blade Runner, with its noir influences, romanticized a specific kind of sci-fi melancholy. In the future, you could be sad and worrying about Replicants. But everything was also going to be effortlessly cool.

Blade Runner: The Final Cut is streaming now on Netflix.