It’s unlikely even the most gifted psychic could have foreseen the problems 1983 telepathic sci-fi Brainstorm would endure during its turbulent route to the big screen. MGM ran into financial difficulties and pulled the plug on the almost-complete project, with only a last-minute deal with insurance company Lloyd’s of London saving it from gathering dust on shelves. Filmmaker Douglas Trumbull was apparently too preoccupied with the film’s special effects to guide his talented cast: rumor has it leading man Christopher Walken regularly took over the director’s chair. And then there was the tragic and mysterious death of Natalie Wood.

Brainstorm was intended to be Wood’s comeback. The three-time Academy Award nominee had struggled to parlay her 1960s success into the following decade, with her only movies, Peeper and Meteor, both flopping. Instead, Brainstorm became her posthumous swansong when, during a production break vacation with husband Robert Wagner and co-star Walken, she was found drowned near Santa Catalina Island. Her sister Lana was used as a stand-in for the film’s few remaining shots.

Perhaps deterred by the negative press, delayed release (it arrived in theaters two years after wrapping), and the macabre prospect of watching a Hollywood icon unknowingly deliver her final performance, Brainstorm failed to recoup its $18 million budget. Those who ignored all the surrounding drama, however, were rewarded with a thought-provoking and visually dazzling attempt to answer one of life’s ultimate, and sadly pertinent, questions: is there life after death?

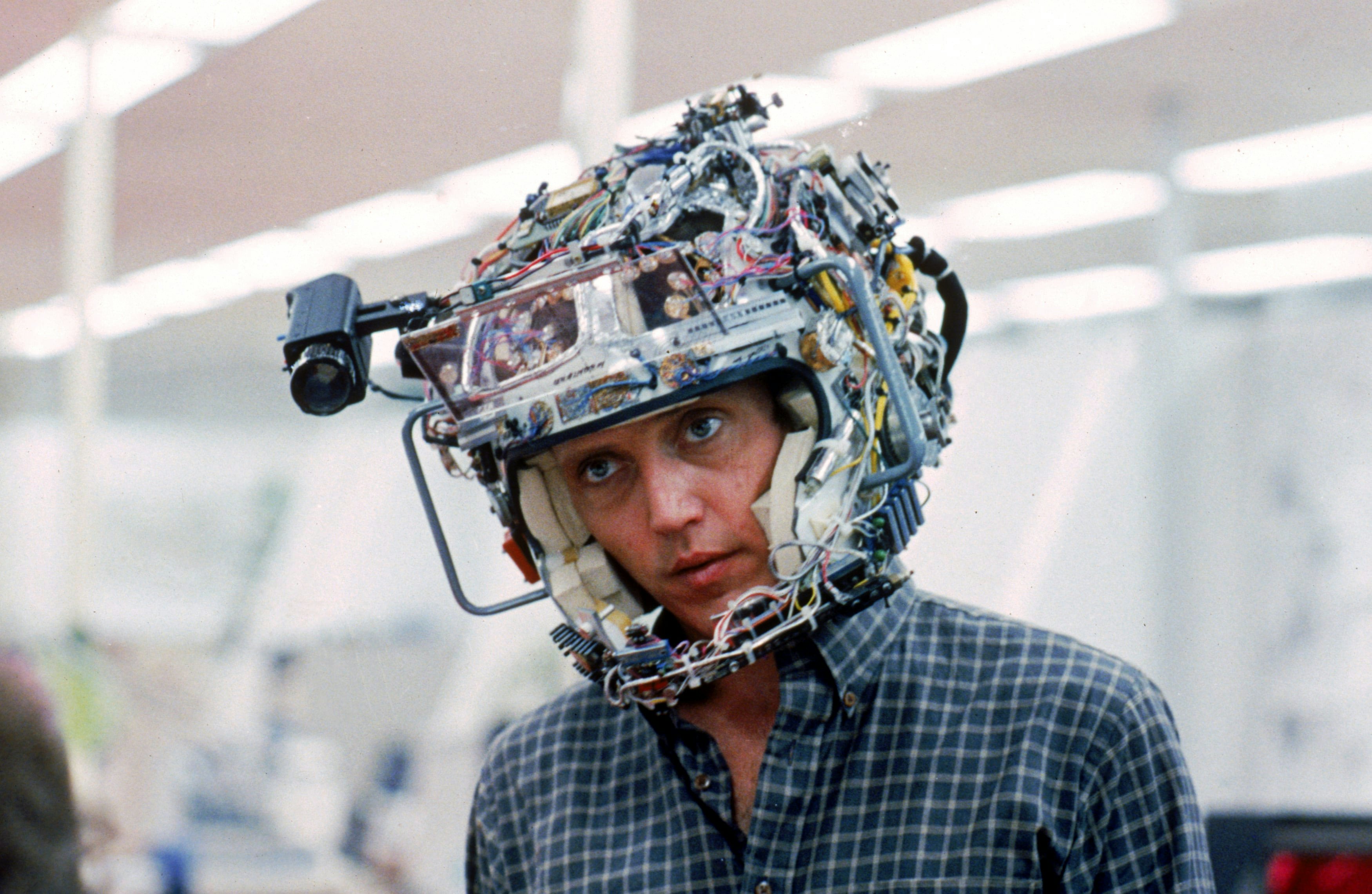

That’s not something the team of scientists, which includes Walken and Wood’s estranged spouses Michael and Karen Brace, Louise Fletcher’s Dr. Lillian Reynolds, and Cliff Robertson’s research facility manager Alex Terson, set out to explore. As shown by an amusing opening in which Michael eats a steak dripping in marshmallow sauce by proxy, their brain-computer interface has been designed to transfer sensations from one person to another. “You’ve blown communication, as we know it, right out of the water,” an excitable Alex proclaims. When Michael plays a recording from his estranged wife, it becomes apparent memories and emotional experiences can be transmitted too.

Trumbull, who abandoned his FX duties on Blade Runner for Brainstorm, never got to display his pioneering invention Showscan, a process in which frames are projected 2.5 times quicker than the average movie. But the way the virtual reality sequences are depicted, especially for the early 1980s, is still far more immersive than the scientists’ rather cumbersome headset would suggest. You can understand why the team’s financial backers give the go-ahead after being treated to a snowmobile expedition, roller coaster ride, and canapes from a scantily-clad waitress from the comfort of their office chairs.

Of course, things go awry. Proving all tech advances eventually lead to porn, Hal (Joe Dorsey) attempts to achieve the world’s longest orgasm by splicing a sex tape together, an abuse of the machinery that doesn’t end well. And when chain-smoking Lillian realizes she’s suffering a fatal heart attack, she records her final minutes for posterity and inadvertently creates a snuff tape.

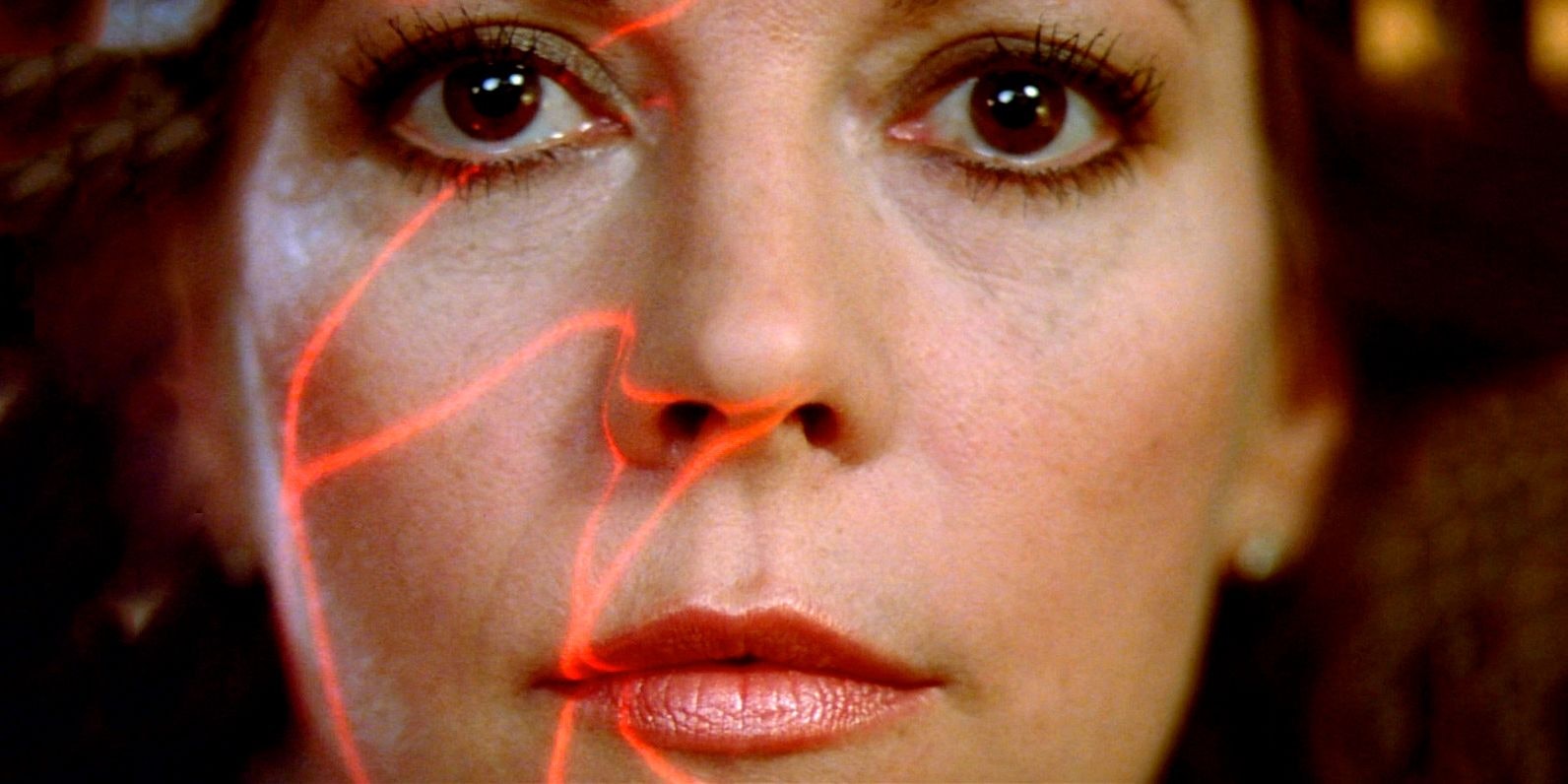

Beating Ringu to the punch by a good 15 years, Brainstorm’s sudden detour into body horror sees anyone who replays Lillian’s final moments succumb to a heart attack themselves. In Michael’s case, he’s able to modify the technology to avoid such a fate. But pressured to endure by suits interested in capitalizing on its military potential, poor project member Gordy (Jordan Christopher) isn’t so lucky.

It’s here where the film takes another sidestep, this time less successfully, into pure espionage. Undeterred by the fact it’s almost taken his own life, Michael becomes obsessed with viewing the tape in its entirety. However, with the offending item now locked away by the powers that be, he and Karen are forced to concoct an elaborate plan for its retrieval.

The heist itself, which involves the pair throwing the surveillants off the scent by feigning a fight while simultaneously hacking into the firm’s computer system, is a perfectly adequate spot of industry sabotage. It also gives Wood, whose character had previously been something of a bland bystander, something to sink her teeth into. Yet the chaos that ensues, particularly the overload of polystyrene and foam that swamps the laboratory floor, risks turning what was an intelligent and often chilling meditation on the power of memory and mortality into an episode of Robots Do the Funniest Things.

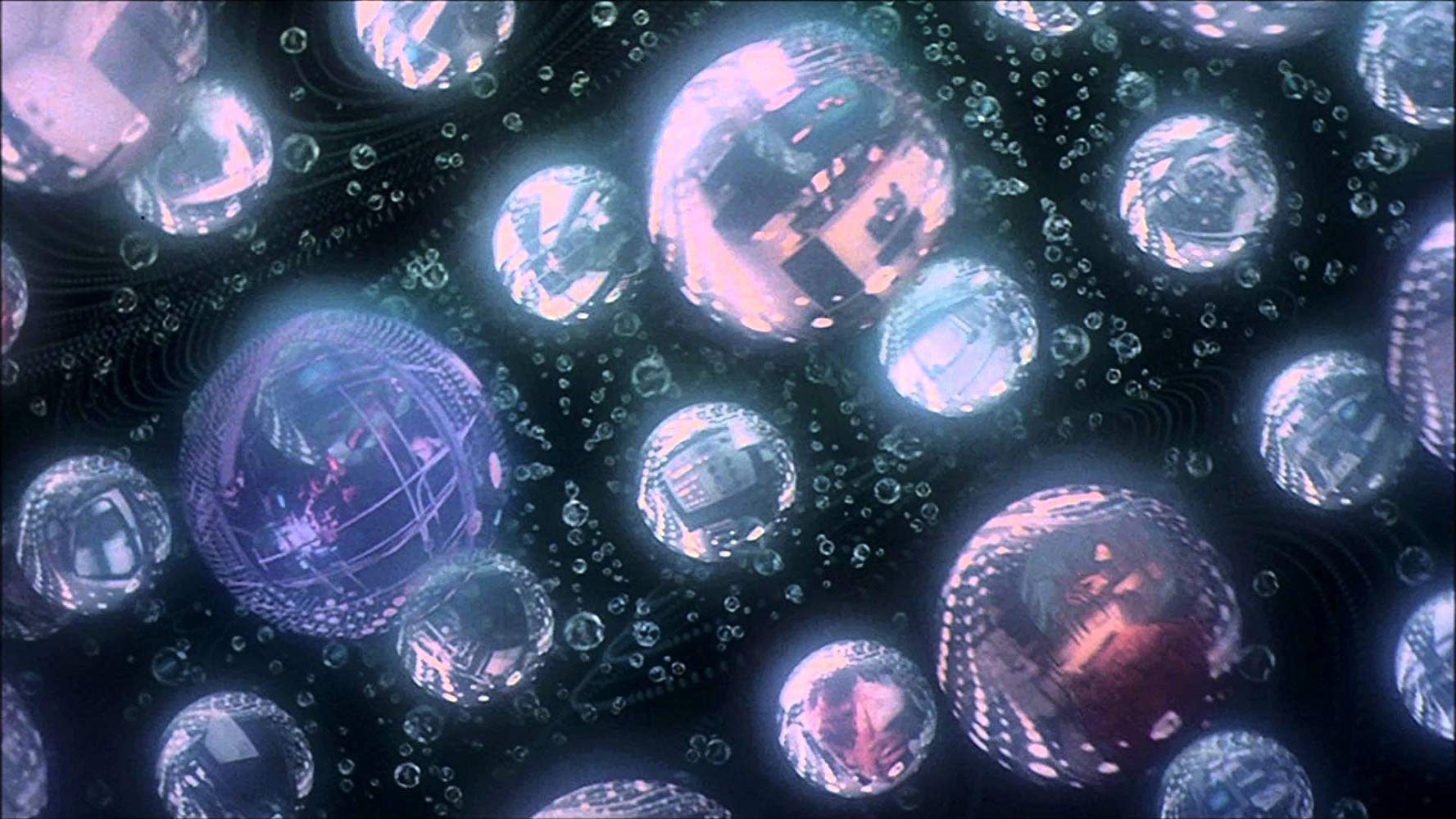

Luckily, Trumbull pulls things back with another striking piece of cinematic imagery as Michael finally gets his eyes on Lillian’s deathly souvenir, once again only just surviving his self-inflicted ordeal. Disturbing and awe-inspiring in equal measure, his visions of the afterlife veer from kaleidoscopic abstractions to visions of angels gravitating towards the big white light, with James Horner’s dark, dissonant score only adding to the discombobulation.

Trumbull became so disillusioned by all the behind-the-scenes problems he vowed never to make another feature film (his only subsequent credits were visual effects consultant on Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life and outlandish adventure drama The Man Who Killed Hitler and Then the Bigfoot). That’s a shame as, like his 1972 eco-themed predecessor Silent Running, Brainstorm is an intelligent blend of melodrama, ahead-of-its-time VFX, and challenging science-fiction that treads that fine line between absurdity and plausibility much better than its troubled reputation would suggest.