Some debates among superhero fans will never be resolved. Superman vs. Batman. Iron Man vs. Captain America. DC vs. Marvel. But if there’s one thing everyone seems to agree on, it’s that 1986 is the most important year in comic book history. The argument why is simple — that one year saw the release of several groundbreaking comics:

- Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, an epic story about an elderly Batman who comes out of retirement to save Gotham City in the face of American decline.

- Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen, a meticulous deconstruction of the entire superhero genre that’s also just a damn-good comic.

- Art Spiegelman’s Maus, which retold the story of the Holocaust to terrific effect in comic book form.

- Other notable events in 1986 include the conclusion of DC’s Crisis on Infinite Earths, which invented the superhero cross-over event as we know it; and the founding of Dark Horse Comics, which would go on to publish Sin City, Hellboy, The Umbrella Academy, and more.

All three of these comics pushed the limits of the art form with mature, gritty stories that would shape the industry for decades to come. But perhaps most crucially, they also changed the very definition of the term “comic book.”

“It became apparent that comics were a medium rather than a genre,” Gibbons, who illustrated Watchmen, tells Inverse. “They didn't have to be straightforward superhero stories or straightforward adventure stories. You could tell all kinds of stories.”

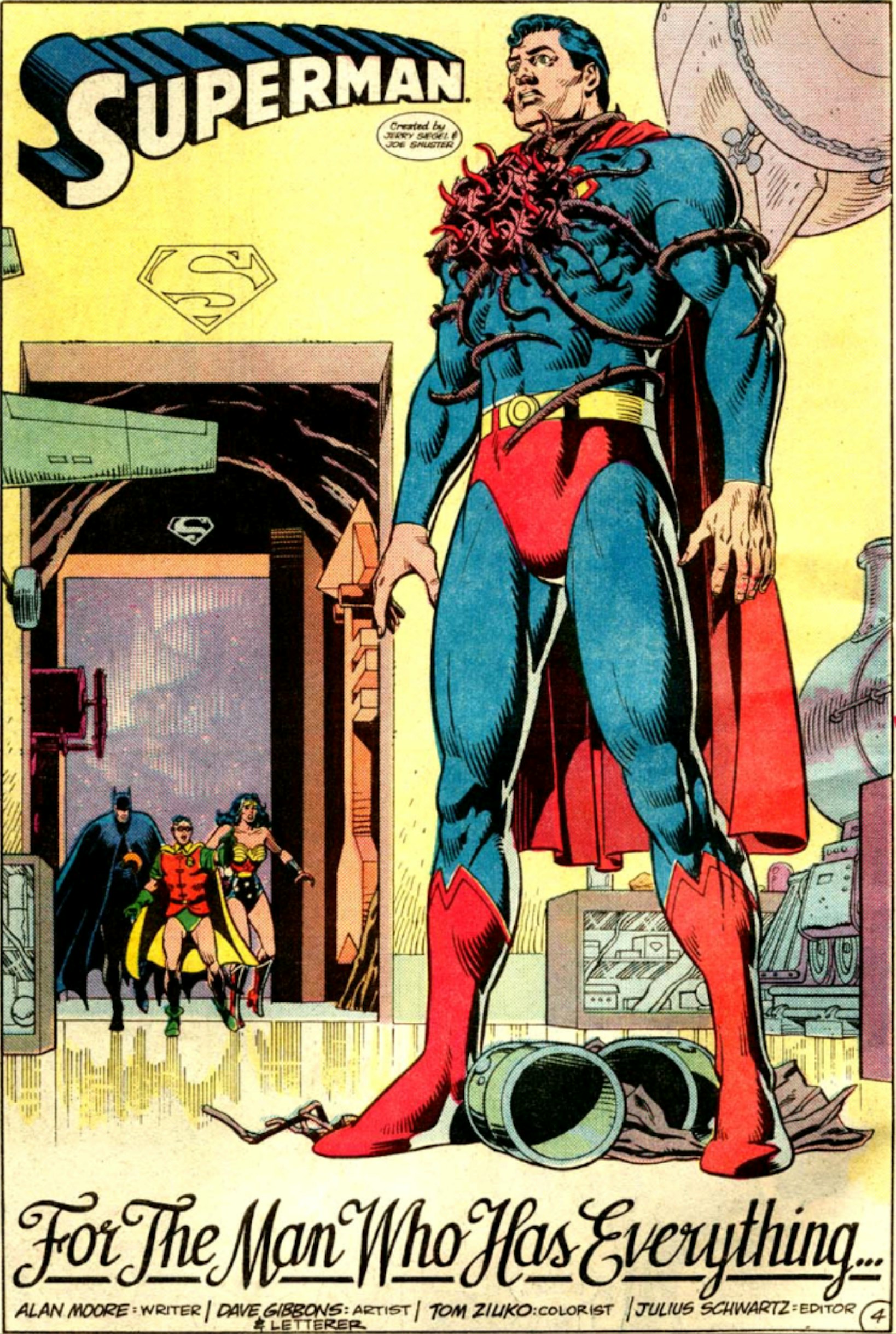

But before Gibbons and Moore could deconstruct the entire superhero genre with Watchmen and change comics forever, they had to take on the most iconic superhero of them all.

Released in 1985, “For the Man Who Has Everything,” is a Superman story unlike anything that came before (or after). The comic traps its hero in an alternate universe where his home planet of Krypton was never destroyed and he never left for Earth. Instead, Kal-El (aka Superman) lives a simple, fulfilling life with his wife and children, but what should feel like a utopia quickly gives way to social upheaval and violence. Moore and Gibbons imagine a version of Krypton that reflects the worst of our own society: crime, drugs, riots, xenophobia, police brutality, and a Ku Klux Klan-esque rally all quickly overwhelm Superman’s vision of a perfect life.

In just 40 pages — while also fitting in a B-plot where Wonder Woman, Batman, and Robin fight an evil alien — “For the Man Who Has Everything” tells a powerful allegorical story that still resonates.

“It was showing the effect of fascist thinking,” Gibbons says.

“For the Man Who Has Everything” paved the way for the sort of social and political commentary we now take for granted in mainstream superhero stories. Without this one comic (and the deluge of instant classics that followed a year later) today’s superheroes would be a lot less interesting. But to understand how this shift was even possible, we have to go back to a time when a generation that grew up on comic books finally got a chance to make some of their own.

The First Comic Book Generation

Gibbons grew up in London in the 1950s and ‘60s. He’s part of a generation that came of age right when mainstream American comics first arrived in the UK, starting in 1959.

“We were like 10 years old,” he says. “So we were the absolute target for these kind of comic books.”

That group includes Gibbons and Moore, along with Brian Boland (who worked on early Judge Dredd comics and illustrated 1988’s Batman: The Killing Joke) and Kevin O'Neill (who co-created The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen). All four of them also contributed to 2000 AD, a British comics magazine that published edgier stories and served as a breeding ground for new talent when it launched in 1977.

By the 1980s, those kids who had grown up on comics were ready to unleash their vision on a mainstream audience. Their work would be hailed as dark and edgy, but if you ask Gibbons, the one thing that unites them is that they took comic books seriously.

“There were a lot of commercial artists who really wanted to do proper illustration — magazine illustration, gallery illustration — who looked upon comics as a kind of way of paying the rent, and that was true both of artists and writers,” Gibbons says. “My generation was the first one that thought: We want to make our lives’ work in comics.”

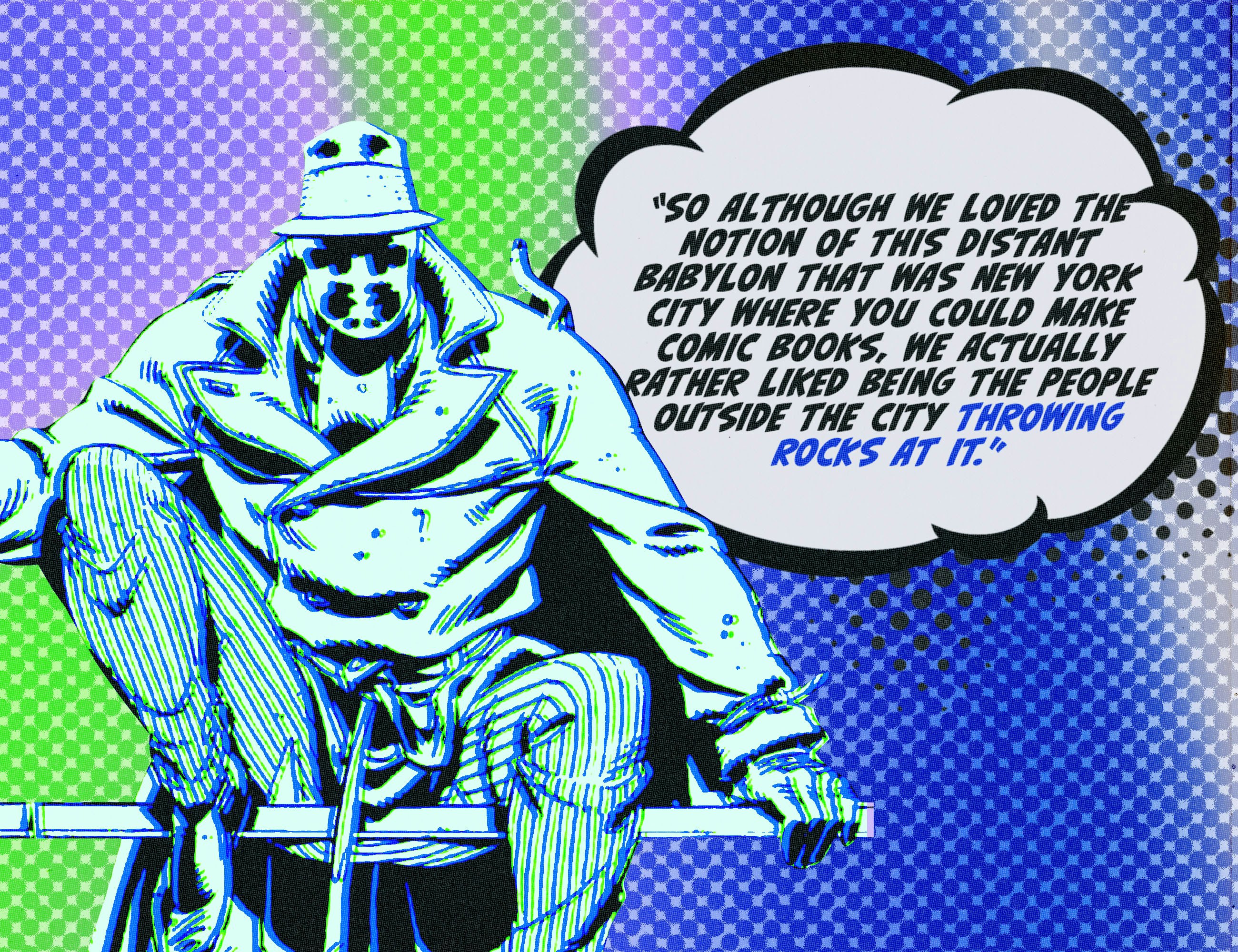

At the same time, Gibbons and his cohort saw themselves as outsiders for one simple reason: comic books were overwhelmingly a U.S. export.

“We sort of brought our own British sensibility towards the American material,” Gibbons says. “So although we loved the notion of this distant Babylon that was New York City where you could make comic books, we rather liked being the people outside the city throwing rocks at it.”

Outsiders or not, the Americans came knocking. DC, in particular, was excited by the fresh perspective on display in 2000 AD and sent two of its top editors, Dick Giordano and Joe Orlando, to the U.K. to recruit. Before too long, Gibbons and Moore were working for DC, and it was only a matter of time before they got their hands on the Man of Steel.

For the Man Who Has Everything

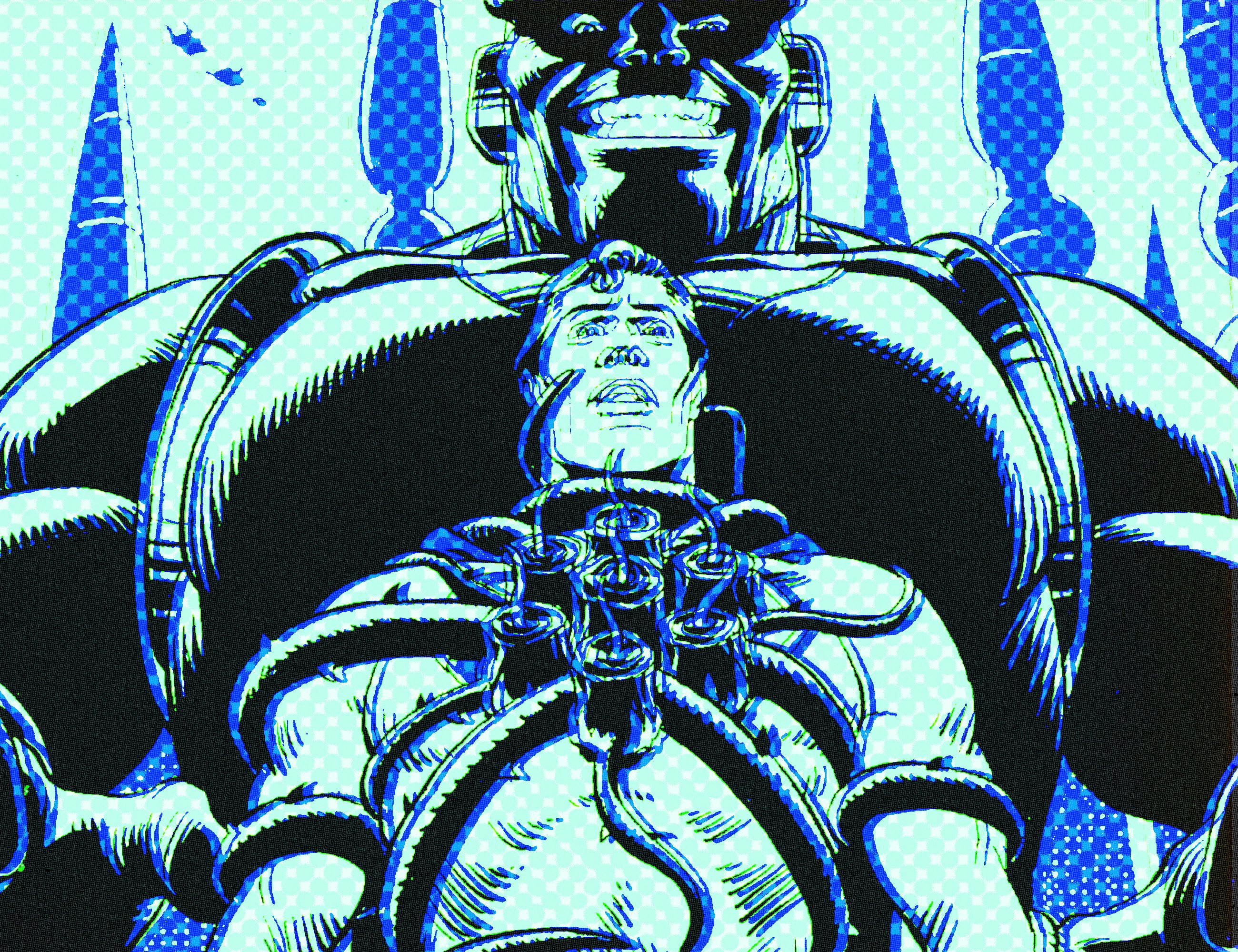

The plot of “For the Man Who Has Everything” hinges on an alien plant called Black Mercy, which was invented for this comic. It’s a parasitic species that grows into its host, neutralizing all their senses and leaving them paralyzed while sending their consciousness to a fantasy based on their deepest desires. For Superman, it turns out that’s a life where Krypton never blew up.

At the start of the comic, Batman, Robin, and Wonder Woman travel to Superman’s Fortress of Solitude for his birthday, but before they can arrive, an evil alien named Mongul shows up and traps Kal-El with the Black Mercy. Our heroes try to fight the villain, but he’s too powerful. Their only hope is Superman, who’s stuck in a fantasy world of his own creation.

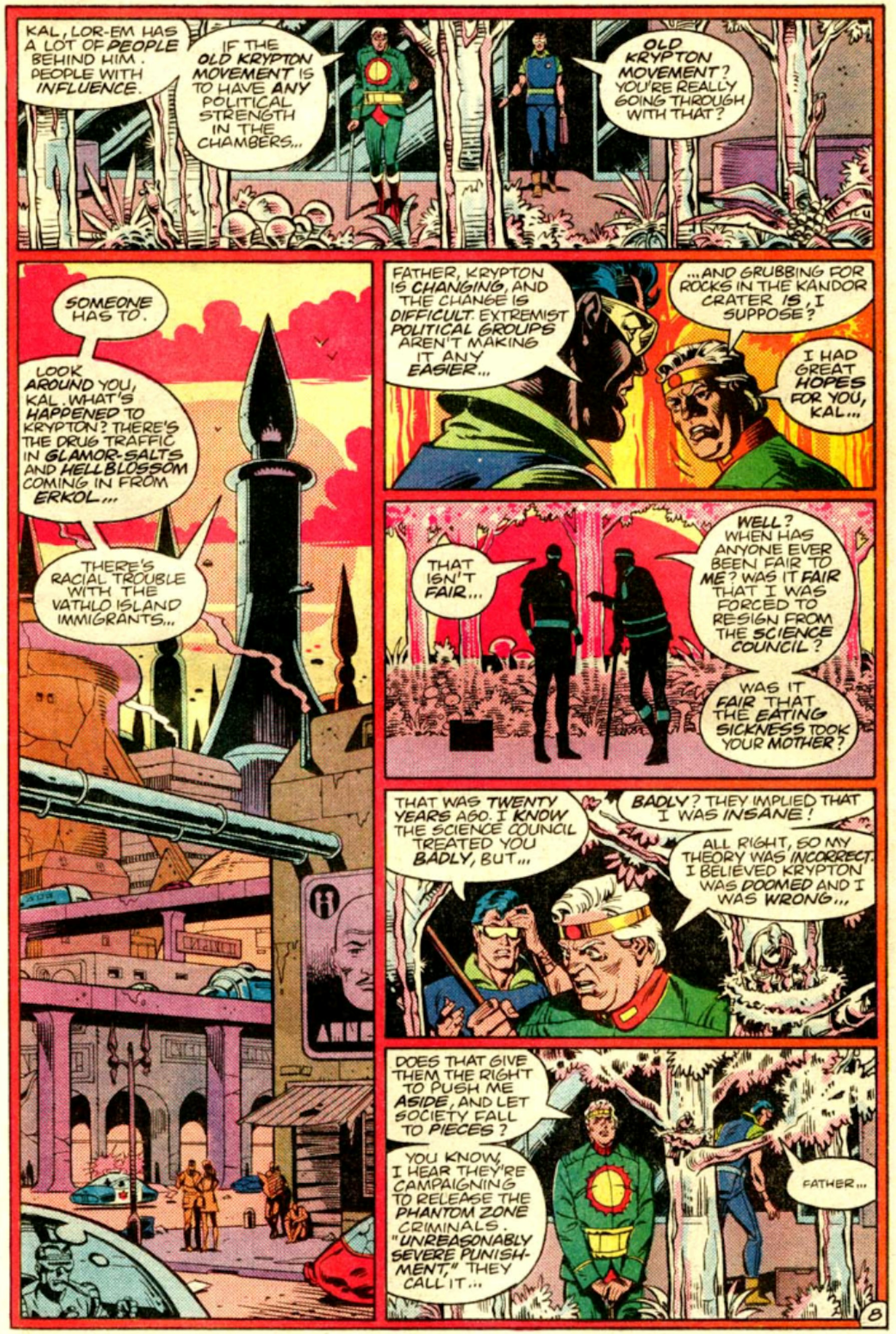

Inside Superman’s brain, however, that fantasy soon becomes a nightmare. On his birthday, Kal-El visits his dad, Jor-El, who reveals that he’s allied with a religious political faction to regain the influence he lost after incorrectly predicting that an asteroid was about to smash into the planet. Superman tries to dissuade his father, who begins to rant about decaying social standards. In a particularly striking panel, Jor-El’s horrible words carry us down the page, revealing the glimmering spires of a modern city and the crime-ridden streets below.

This vision of Krypton may seem jarring — Superman’s home world was supposed to be a utopia, right? — but the idea came from the very foundations of his character.

“What's hinted at in the mainstream Superman comic books was that there was some friction in the society,” Gibbons says. “Kal-El's father was warning of imminent doom, but the ruling council chose to disregard it. So there was this political subtext.”

From that nugget of an idea, Gibbons and Moore extrapolated an entire story, imagining the life Superman might have known if his father had been wrong — and how the planet of Krypton wasn’t as perfect as Kal-El imagined.

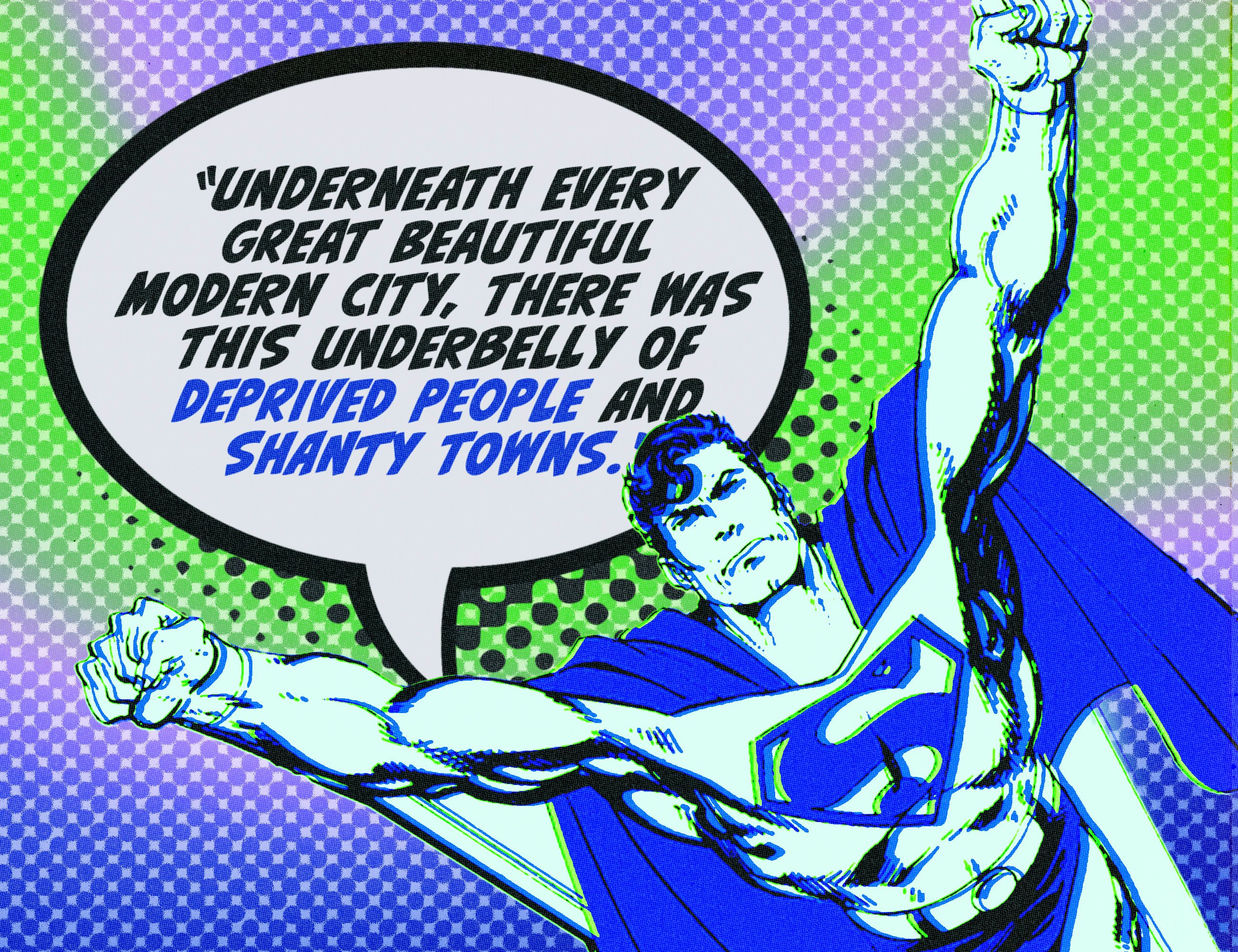

“We'd only ever seen the soaring spires of Krypton, never the reality for most of the people,” Gibbons says. “This wonderful, heavenly, fabled place. We were applying reality to something that was quite an accepted fantastic and unreal truth. The idea was that underneath every great beautiful modern city, there was this underbelly of deprived people and shanty towns.”

Later in the comic, Kal-El attempts to flee the city with his son only to get caught in the middle of a political riot. Religious zealots clad in red robes with flaming crosses flood the street as Jor-El takes the stage as their new leader. Militarized police officers dressed like Judge Dredd (a subtle nod to Gibbons and Moore’s earlier 2000 AD work) push back against counter-protestors.

You can see the seams of Superman’s fantasy world starting to fall apart as they give way to the harsh realities of the real world that raised him. Released smack dab in the middle of conservative political rule in both the U.S. and the U.K., perhaps it's no surprise that this vision of Krypton collapses into far-right political violence.

“It's evocative of the kind of Nazi rallies where there’s this tremendous sense of drama and people being part of a mass movement,” Gibbons says.

Superman can only take so much before he snaps out of it and returns to reality. We get one final fight before the heroes defeat the villain by trapping Mongul in his own fantasy of bloody conquest. (Batman is also briefly ensnared by the Black Mercy and later reveals that in his fantasy his parents survived and he married Batwoman.) Superman and Wonder Woman share a steamy birthday kiss. The end.

“The Man Who Has Everything” has inspired countless spinoff stories and adaptations. Warner’s Justice League Unlimited cartoon even attempted a 20-minute version, which frustratingly sands off anything even close to socio-political commentary.

But the comic’s real legacy isn’t any one story, it’s the way it freed other writers and artists to explore the gritty underbelly of mainstream superheroes — even the most ethical and moral among them. However, it’s always possible that some director could step in and try to do justice to the original comic.

“I think it's a great story that Alan wrote,” Gibbons says, “and I think it's just about the right length for a really interesting movie.”

Watchmen and regrets

If the driving question of “The Man Who Has Everything” is: What if Krypton was real? then the question at the heart of Gibbons and Moore’s follow-up, Watchmen, is: What if superheroes were real?

“We reasoned that if there really were superheroes, they wouldn't necessarily be popular,” Gibbons says. “They might be suspected of using their superior powers to do something against us ordinary people.”

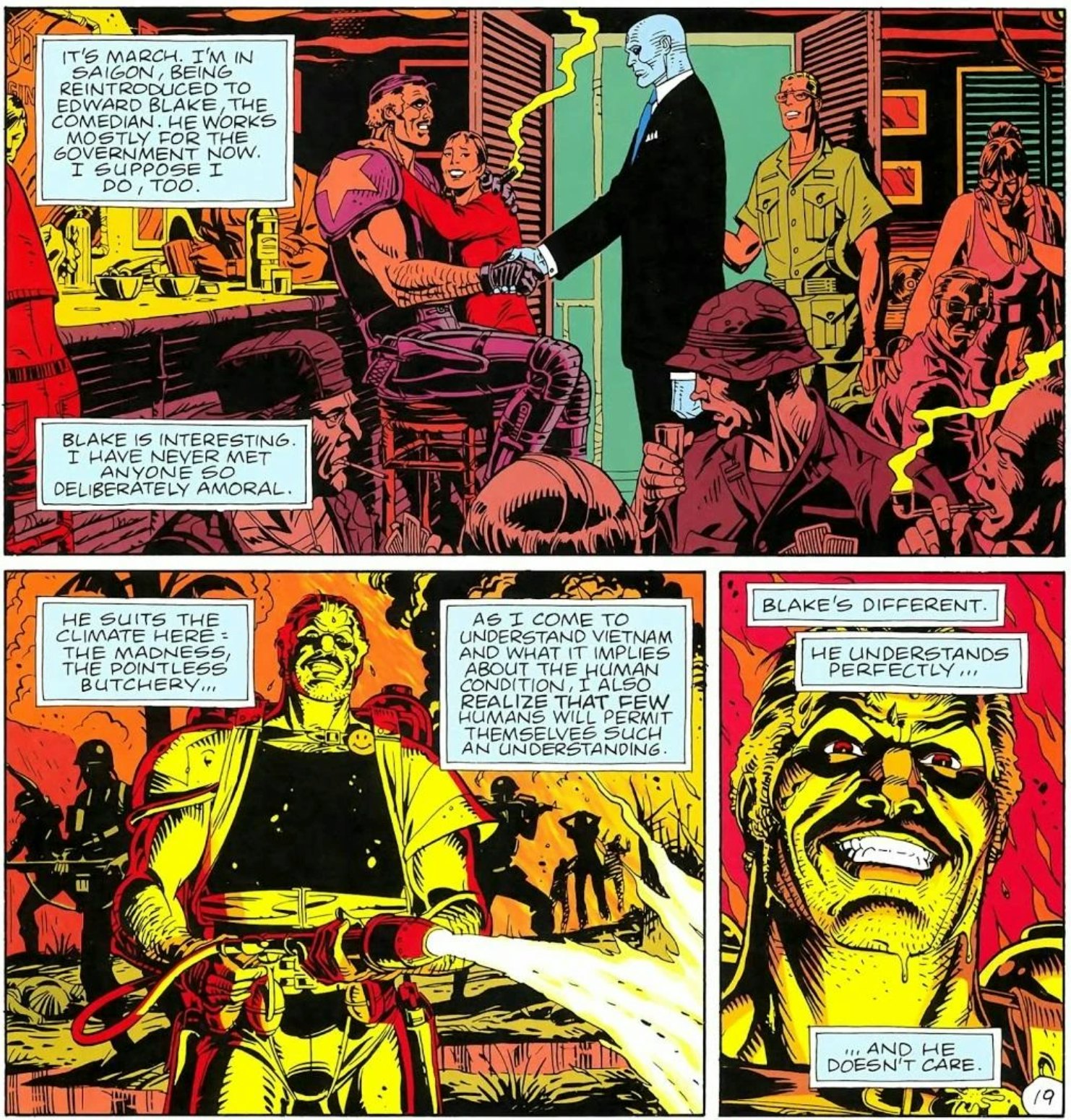

The superheroes in Watchmen help impose U.S. might around the world, changing the tide of the Vietnam War in America’s favor and turning the United States into the planet’s sole nuclear force thanks to the living embodiment of atomic power known as Dr. Manhattan. But, as Gibbons points out, these characters “weren't necessarily heroes,” or, at least, “that wasn't their main motivation.” Instead, the characters in Watchmen are rapists, murderers, and criminals who barely care about the humans they’re supposed to protect.

Watchmen marked a turning point in the comics industry. Just like how Gibbons and Moore represented a generation of writers and artists who grew up reading comic books, Watchmen was a story written for fans who were steeped in superhero history. You didn’t need to explain that Nite Owl was a stand-in for Batman. It was obvious to this audience, which left room for layers of meta-commentary and subtext that an earlier generation wouldn’t have understood.

Unlike his longtime conspirator Alan Moore, Gibbons has never disavowed Watchmen. He’s even consulted on some of the adaptations and praises the HBO show. But if there’s one thing he regrets, it’s how the comic book industry took the wrong lesson from the success of his work.

“I think there was a certain downside, which was that suddenly a lot of American comic books became very dark and gritty in a way that was a little bit superficial,” Gibbons says. “I just feel sorry for the decade or so grim and dirty comics that people had to endure.”

At the time, he and Moore even considered pushing back on that trend by taking on another, slightly less iconic, DC superhero.

“If Alan and I had done anything after Watchmen, the thing that we always talked about was doing a reimagining of Captain Marvel/Shazam because we just loved that sort of fairytale, slightly ridiculous, humorous tone,” Gibbons says.

If one thing is clear from speaking to Dave Gibbons, it’s that he’s proud of all the work he’s done in comics. And he should be. Beyond “For the Man Who Has Everything” and Watchmen, he also illustrated iconic Green Lantern comics, helped create the Kingsman with Mark Millar, and even has credits for developing early Doctor Who characters. The list goes on, but there’s no denying that Gibbons’ biggest influence came in 1986, and one year before it when he brought one of the best, and darkest, Superman stories to life.

Inverse's 2024 Superhero Issue, guest edited by Zack Snyder, explores the genre for what it is: a profound commentary on our shared human experience. Dive into the full issue here.