Aquaculture in Indonesia produces more than twice as much fish as captured fisheries. This sector has surged, with production rising from 2.4 million tonnes in 2010 to 6.4 million tonnes in 2019.

In 2024, Indonesia aims for 10.4% annual output volume growth for aquaculture. Globally, as wild capture fisheries production is slowing down, seafood production has shifted to aquaculture. Aquaculture generates 49% of the world’s seafood, and is currently the fastest-growing food production sector. So it is unsurprising that the aquaculture sector is one of Indonesia’s development priorities.

However, the growth in aquaculture development comes with environmental impacts. These include deforestation of mangroves for aquaculture farming, and the discharge of waste from aquaculture activities.

Our recent report, “Trends in Marine Resources and Fisheries Management in Indonesia: A Review”, published by the World Resources Institute Indonesia, showed the country’s dependency on aquaculture for food security, as well as its challenges towards achieving sustainable aquaculture management.

Our report found Indonesia produces almost half of its seafood from farms, including freshwater, brackish water, and mariculture, with more than 70% of freshwater aquaculture consumed domestically.

In that report, we and our co-authors outlined three steps to ensure sustainable development of aquaculture, with a focus on shrimp and seaweed farming.

Shrimp is Indonesia’s most valuable aquaculture commodity and the country’s top fisheries export, while the seaweed industry has the potential for growth and could provide a source of income for middle- to low-income communities.

1. Consistent and collaborative planning

Indonesia has the potential to revitalise and restore currently degraded aquaculture zones, especially in shrimp aquaculture. Shrimp aquaculture is the main cause of mangrove degradation in Indonesia.

Degradation is worst along the north coast of Java, the east coast of Kalimantan, and in southeast Sulawesi.

Indonesia’s ambitious goal of almost doubling shrimp aquaculture production to 2 million tonnes by 2024 poses a threat to mangroves across the country.

Recognizing the threat, the government enacted Coordinating Economic Ministerial Regulation Number 4 of 2017, a regulation targeting the rehabilitation of 1.8 million hectares of mangroves.

To achieve both the production and rehabilitation goals, the government will need careful planning, including intensification – using available resources to boost production from existing aquaculture areas – rather than expansion.

The Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries must collaborate with provincial governments to ensure that planning and review are tailored to each province’s development priorities.

Twenty-seven provinces in Indonesia have enacted coastal and small island spatial plans (RZWP3K). It is important for the planning areas to have clear boundaries between zones that are reviewed annually, especially where the coastline is changing due to sea level rise and other factors.

Data on coastal and marine areas, such as marine resources, habitats, and users, must be collected and managed effectively. Data should be collected in formats that allow for easy transfer between agencies when necessary.

Having good data management would help make better decisions when planning for aquaculture. This means taking into account important habitats like mangroves and seagrass, as well as other priorities that might compete with aquaculture for space, such as tourism and maritime transport.

2. Establishing suitable policies for different types of aquaculture

Different types of aquaculture require different management systems. For example, research shows that seaweed farming in eastern Indonesia is causing significant damage to important seagrass ecosystems – which play a vital role in combating climate change.

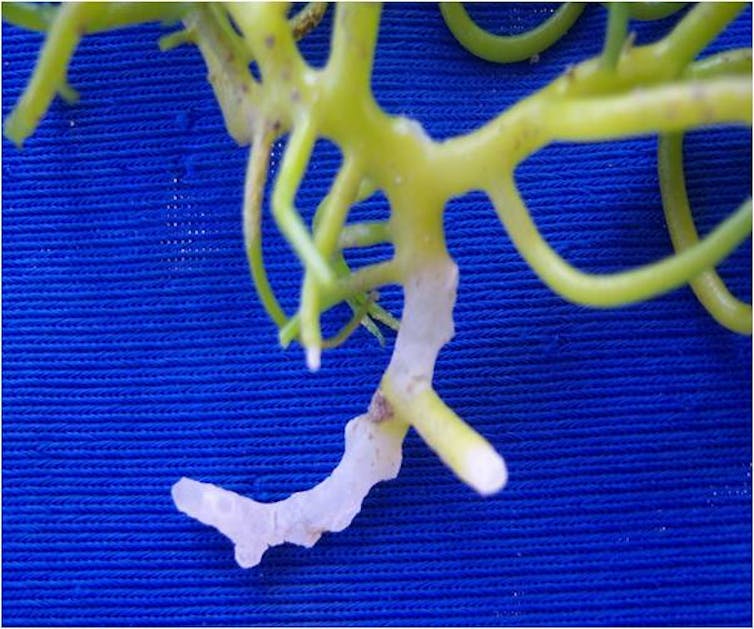

Additionally, the government needs to create a national strategy to address the spread of diseases that can reduce the productivity of seaweed farming. In Konawe District, located in South East Sulawesi, seaweed production is being affected by an outbreak of “ice-ice” bleaching disease.

To ensure the responsible and sustainable growth of seaweed throughout Indonesia, authorities need to establish more suitable policies. This should involve identifying suitable locations for farming and processing within the country to enhance the value chain.

If Indonesia encourages companies to process seaweed products within the country, it could improve the value of exports and bring more benefits to the communities involved in the process.

3. Accessible capacity building

Indonesia’s aquaculture has the potential to increase employment, retain employment in rural areas, and create dignified jobs.

However, labor productivity is relatively low, with an average production of less than 1 ton per fish farmer in 2016. This is much lower than the rates in other countries like China and Norway, where it was much higher at 10 tons and 165 tons respectively.

To address this issue, the government could establish a training program for aquaculture farmers that focuses on proper environmental management for intensive aquaculture pond systems.

The training program could help fish farmers access and adopt innovative practices. This includes access to subsidized insurance that reduces risk and incentivizes sustainable environmental management, as well as new technologies to improve their yields.

The capacity-building programs should also be inclusive of women, as they play an important role in the processing phase of the aquaculture industry. Providing training during the post-harvest phase can also help reduce waste and loss while increasing net production.

Indonesia’s aquaculture production is expected to increase in the future. To ensure sustainable growth, it’s important to enforce consistent coastal and marine spatial planning, enhance the seaweed industry policy, and strengthen the government’s capacity-building programs.

These actions will ensure that the aquaculture industry can provide food security and boost the ocean economy, without harming the environment or the local communities.

Ines Ayostina was a Researcher at the World Resources Institute Indonesia during the development of the report. The report is funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Lucentezza Napitupulu was an Economic Researcher at World Resources Institute Indonesia during the development of the Report. The Report is funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.